The Stewart Detention Center is seen through the front gate, Friday, November 15, 2019, in Lumpkin, Ga. The rural town is about 140 miles southwest of Atlanta and next to the Georgia-Alabama state line. The town’s 1,172 residents are outnumbered by the roughly 1,650 male detainees that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement said were being held in the detention center in late November. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

By KATE BRUMBACK, DEEPTI HAJELA and AMY TAXIN, Associated Press

LUMPKIN, Ga. (AP) — In a locked, guarded courtroom in a compound surrounded by razor wire, Immigration Judge Jerome Rothschild waits—and stalls.

A Spanish interpreter is running late because of a flat tire. Rothschild tells the five immigrants before him that he’ll take a break before the proceedings even start. His hope: to delay just long enough so these immigrants won’t have to sit by, uncomprehendingly, as their futures are decided.

“We are, untypically, without an interpreter,” Rothschild tells a lawyer who enters the courtroom at the Stewart Detention Center after driving down from Atlanta, about 140 miles away.

In its disorder, this is, in fact, a typical day in the chaotic, crowded and confusing U.S. immigration court system of which Rothschild’s courtroom is just one small outpost.

Shrouded in secrecy, the immigration courts run by the U.S. Department of Justice have been dysfunctional for years and have only gotten worse. A surge in the arrival of asylum seekers and the Trump administration’s crackdown on the Southwest border and illegal immigration have pushed more people into deportation proceedings, swelling the court’s docket to 1 million cases.

“It is just a cumbersome, huge system, and yet administration upon administration comes in here and tries to use the system for their own purposes,” says Immigration Judge Amiena Khan in New York City, speaking in her role as vice president of the National Association of Immigration Judges.

“And in every instance, the system doesn’t change on a dime, because you can’t turn the Titanic around.”

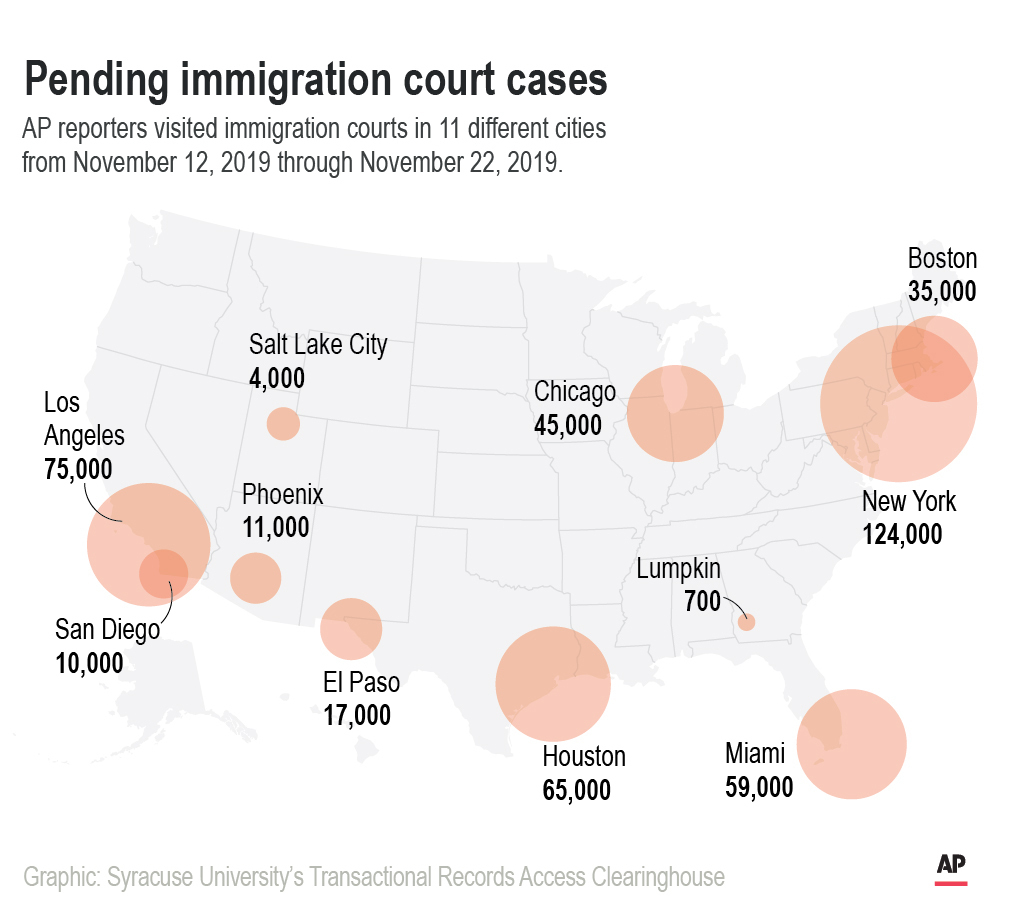

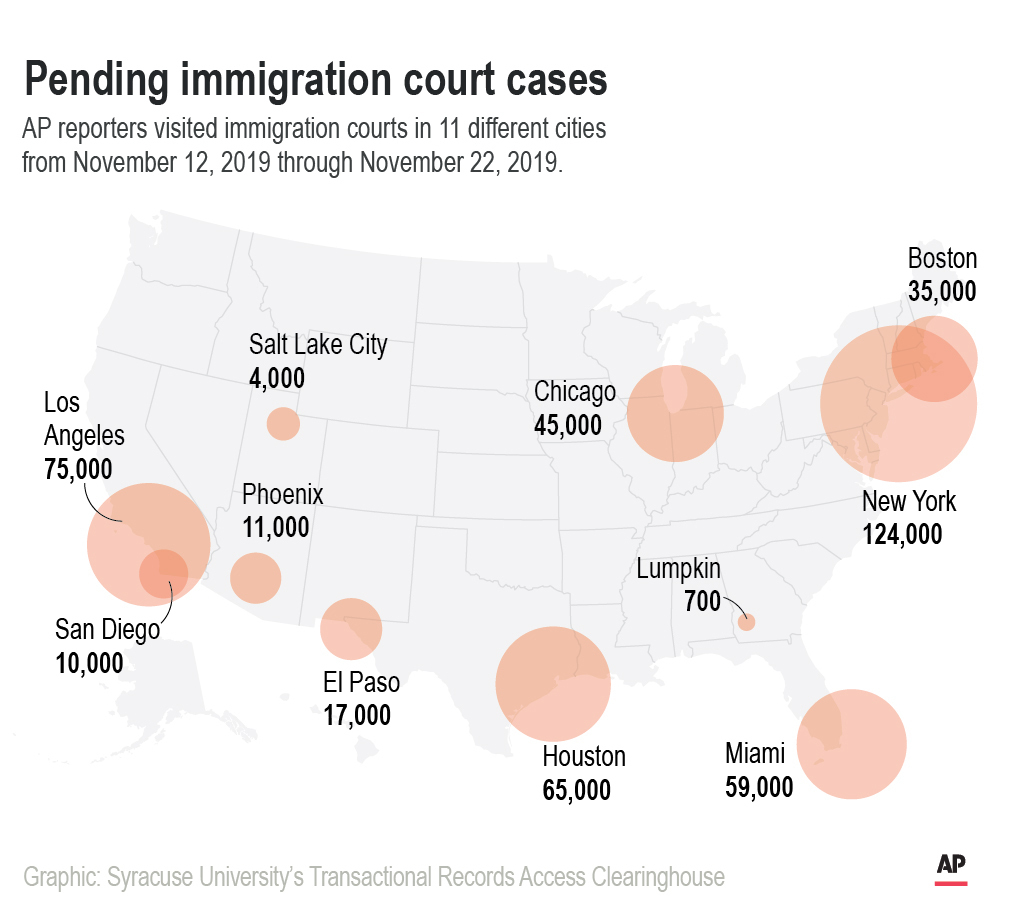

AP reporters visited immigration courts in 11 different cities from November 12, 2019 through November 22, 2019.;

The Associated Press visited immigration courts in 11 different cities more than two dozen times during a 10-day period in late fall. In courts from Boston to San Diego, reporters observed scores of hearings that illustrated how crushing caseloads and shifting policies have landed the courts in unprecedented turmoil:

- Chasing efficiency, immigration judges double- and triple-book hearings that can’t possibly be completed, leading to numerous cancellations. Immigrants get new court dates, but not for years.

- Young children are everywhere and sit on the floor or stand or cry in cramped courtrooms. Many immigrants don’t know how to fill out forms, get records translated or present a case.

- Frequent changes in the law and rules for how judges manage their dockets make it impossible to know what the future holds when immigrants finally have their day in court. Paper files are often misplaced, and interpreters are often missing.

In Georgia, the interpreter assigned to Rothschild’s courtroom ends up making it to work, but the hearing sputters moments later when a lawyer for a Mexican man isn’t available when Rothschild calls her to appear by phone. Rothschild is placed on hold, and a bouncy beat overlaid with synthesizers fills the room.

He moves on to other cases —a Peruvian asylum seeker, a Cuban man seeking bond— and punts the missing lawyer’s case to the afternoon session.

This time, she’s there when he calls, and apologizes for not being available earlier, explaining through a hacking cough she’s been sick.

But by now the interpreter has moved on to another courtroom, putting Rothschild in what he describes as the “uneasy position” of holding court for someone who can’t understand what’s going on.

“I hate for a guy to leave a hearing having no idea what happened,” he says, and asks the lawyer to relay the results of the proceedings to her client in Spanish.

After some discussion, the lawyer agrees to withdraw the man’s bond petition and refile once she can show he’s been here longer than the government believes, which could help his chances.

For now, the man returns to detention.

Mail boxes for various departments line a hallway as detainees walk through the Stewart Detention Center, Friday, November 15, 2019, in Lumpkin, Ga. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

***

In a federal building in downtown Manhattan, the docket lists stretch to a second page outside the immigration courtrooms. Crowds of people wait in the hallways for their turn to see a judge, murmuring to each other and their lawyers, pressing up against the wall to let others through.

Security guards pass through and chastise them to stay to the side and keep walkways clear.

Immigration judges hear 30, or 50, or close to 90 cases a day. When they assign future court dates, immigrants are asked to come back in February or March—of 2023.

The country’s biggest immigration caseload is in New York City, spread over three different buildings. One in 10 immigration court cases are conducted there, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

On average, cases on the country’s immigration docket have been churning through the courts for nearly two years. Many immigrants have been waiting much longer, especially those who aren’t held in detention facilities.

With so many cases, immigrants are often double- and triple-booked for hearings. That can turn immigration court into a high-stakes game of musical chairs, where being the odd man out has far-reaching consequences.

Rubelio Sagastume-Cardona has waited two years for a New York judge to consider whether he should get a green card.

The Guatemalan had a hearing date in May but got bumped by another case. On this day, he finds himself competing for his space on Judge Khan’s calendar with someone else’s case—a space Sagastume-Cardona only nabbed because his lawyer switched him with another client, who now must wait until 2023 for a hearing.

“It’s been more difficult to get my client’s case heard than to litigate” it, says his attorney, W. Paul Alvarez. “It’s kind of crazy.”

The protracted delays are agonizing for many immigrants and their relatives, who grapple anxiously with the uncertainty of what will happen to their loved ones—and when.

And it isn’t confined to New York. In myriad courtrooms, similar scenes play out as immigrants and their lawyers jockey for space on too-cramped calendars.

Courts in San Francisco and Los Angeles each have more than 60,000 cases. And cases have been pending an average of more than two years in courts from Arlington, Virginia to Omaha, Nebraska, according to TRAC.

In Boston, Audencio López applied for asylum seven years ago. The 39-year-old left a Guatemalan farming town to cross the border illegally as a teenager in 1997 and soon found a job at a landscaping company where he still works, maintaining the grounds at area schools. But it was just this past November that he headed to the imposing Boston courthouse to learn his fate.

In this Thursday, November 21, 2019 photo Audencio López, center, is seated with two of his children during an interview with The Associated Press, at their home in Lynn, Mass. (AP Photo/Steven Senne)

He brings his wife and three children into the courtroom, including a baby girl who munches on Cheerios while sitting on her mother’s lap until his case is called.

López tells the judge about his devout Christianity and Bible studies, his kids’ education at a charter school and dreams of going to college, his fear of having to move his children to a dangerous place they’ve never been.

He’s hoping to stay in the country under a provision for immigrants who have lived in the country more than a decade and have American children who would suffer if they were they gone.

After about an hour of questioning, Judge Lincoln Jalelian tells López he’ll take the case under advisement. The government attorney says she won’t oppose granting López a visa due to his “exemplary” record and community service, which means he’ll likely be able to stay.

But even as he dreams of his family’s future in America, López admits the hope and joy are tempered by uncertainty because his wife’s status is still unresolved. She applied separately for asylum five years ago and has yet to have her immigration court hearing.

“It’s a good first step,” López says a week later. He praises God, “but we hope He can show us another miracle.”

***

A toddler’s gleeful screams fill the immigration courtroom in a Salt Lake City suburb as he plays with toy cars while his mother waits for her turn to go before the judge.

Ninety minutes later, the boy is restless, and the 32-year-old woman from Honduras is still waiting. She pulls out her phone, opens YouTube and plays children’s songs in Spanish to calm his cries.

There are many children in the immigration courts, though the courts are hardly a place for kids.

In Chicago, a plastic box of well-worn books in English and Spanish sits in the corner of the court waiting room. But the chairs don’t move and there are no changing tables in the bathrooms, leading a mom to change her newborn’s diaper on a narrow counter between sinks.

Many children have immigration cases of their own. AP reporters saw appearances by children as young as 3. They sit on wooden benches with their parents, grandparents or foster families.

Teenagers scroll through smartphones; a toddler with a superheroes backpack swings his tiny, sneakered feet.

There are also American-born kids tagging along with immigrant parents the government seeks to deport.

The number of children in these courts has swelled since the Obama administration and continues to grow under Trump, with border arrests —many of them children and families— soaring in May to a 13-year high.

Now, nearly one in 10 cases in the immigration courts is a child who came to the country without parents, court data shows. Since September 2018, another 118,000 cases involving parents and c hildre n were placed in fast-tracked proceedings aimed at deciding cases in a year.

The administration aggressively tried to slow the arrival of young migrants by separating families —a policy that was later reversed— and tightening rules for relatives to get them out of detention. But thousands still arrive each month and end up in immigration courts—sometimes, into adulthood.

Verónica Mejía left El Salvador as a young teen and has now lived a third of her life in the United States.

And it took her that long to get her day in a Los Angeles immigration court.

Now 20, Mejía raises her right hand and vows to tell the truth. She says she was barely a teen when a classmate who belonged to the MS-13 gang pressured her to be his girlfriend. After being assaulted and harassed by gang members, she moved to live with her adult sister in a new city and her family later decided to send her north.

Six years later, she has a job in a California warehouse, a boyfriend and an 8-month-old daughter with chubby cheeks and pierced ears waiting down the hall.

Immigration Judge Ashley Tabaddor asks why she didn’t stay with her sister. The government lawyer questions Mejía’s credibility.

The hearing ends, and Tabaddor takes a five-minute break. Mejía sits and waits in the courtroom, tears streaming down her face.

When Tabaddor returns, she says she believes Mejía. But she says she doesn’t qualify for asylum under the law and issues an order for her to return to El Salvador.

Mejía walks down the hall with her lawyer. Her boyfriend hands her the baby.

“We’re going to appeal,” she says, sitting down to nurse the wide-eyed infant. “For her, how am I going to leave her here?”

***

A piece of toast with jam sits on the desk in Tabaddor’s office, half-eaten from the morning’s breakfast though it is nearly lunchtime.

On her computer, there are eight color-coded dashboards showing how close she is to meeting goals set by the Department of Justice for the country’s 440 immigration judges. Like many, she’s nowhere near completing the annual case completion target, and her dashboard is a deep red.

“So far, everyone has told us they’re failing the measure,” says Tabaddor, speaking in her capacity as president of the immigration judges’ union.

While they wear black robes and preside over hearings, immigration judges are employees of the Department of Justice and don’t have the same power or autonomy as criminal court judges.

The Trump administration has made that clear, issuing new quotas and rules for the judges and placing them under tight scrutiny in a push to move cases more quickly through the clogged courts.

In this November 19, 2019, photo, asylum seekers from Central America and Cuba follow an Immigration and Customs Enforcement guard into the Richard C. White Federal Building in El Paso, Texas. (AP Photo/Cedar Attanasio)

The measures have pitted the judges against the agency in a full-on fight. The judges’ union has called for the courts to be made independent and free of government influence. In turn, the Department has asked federal labor authorities to put an end to the union.

“All of this is frankly psychological warfare,” Tabaddor says. “I’ve had so many people say, “I have a mortgage; I have a child who needs braces. I don’t want to fight.'”

In the immigration courts, the friction has taken its toll. Judges are overbooking calendars to try to meet quotas, while the Trump administration has limited their ability to manage dockets as they see fit, adding to the mounting backlog.

Officials also issued rulings making it tougher for immigrants fleeing gangs or domestic violence to win asylum, leading to more denials and potentially more appeals.

In a glass building overlooking the Potomac River from Fall Church, Virginia, officials at the Department’s Executive Office for Immigration Review try to find ways to stay ahead of the ever-growing backlog.

They’re adding interpreters in Spanish and Mandarin, judges and clerks. They’ve started special centers to handle video hearings for immigrants on the U.S.-Mexico border, while smaller cities like Boise, Idaho, that were once served by traveling judges are now video-only.

They’re moving to an electronic system to try to put an end to the heaps of paper files hoisted in and out of courtrooms.

The entire effort is a quest for efficiency, though director James McHenry acknowledges “we’re still getting outpaced” by new cases.

The agency hopes tightening the system can make proceedings more efficient, while remaining fair to all. “We are trying to break down the false dichotomy between fair and efficient,” he says.

The attorneys for Immigration and Customs Enforcement tasked with upholding the country’s immigration laws also feel the crunch. Their numbers haven’t changed even as the docket has swelled, says Tracy Short, the agency’s principal legal adviser.

They’re in court four days a week with caseloads that have doubled from a decade ago, leaving minimal time to prep for hearings.

“I feel like I’m already stretching them to the breaking point,” says Wen-Ting Cheng, who oversees the agency’s 100 trial attorneys in New York.

***

The disorder stretches well beyond the bustling courts of the country’s cities. A lawyer takes a red eye from Los Angeles to Houston, then flies to Louisiana, rents a car and drives for an hour to reach a remote detention facility.

Michael Navas Gómez, a political activist from Nicaragua, is wearing a jail jumpsuit, and ready for his day in court after being detained five months. He and attorney Joshua Greer watch a video monitor for their hearing before an immigration judge who sits 1,000 miles away in Miami, Florida, along with the government’s attorney.

But the stack of documents recounting how Navas Gómez was captured, beaten and burned by pro-government forces is missing. The judge searches for the files while Navas Gómez’s lawyer scrambles to get them sent again so the judge can read them.

The system requires careful choreography among judges, lawyers and language interpreters. Immigration attorneys travel long distances to reach remote courts and follow clients shuffled to different detention facilities, while interpreters crisscross the country to provide translation to immigrants when and where they need it.

There’s so much chaos it’s hard to keep track. At times, an interpreter is missing, or stumbles over dialects or local slang. Video systems fail.

And there are papers everywhere—except, sometimes, where they are supposed to be.

Adding to the problem is that many immigrants don’t have lawyers, and there’s no requirement for the government to provide any for them. So oftentimes, immigrants wind up arguing their cases on their own in an incredibly complex area of law.

At the facility in Lumpkin, Georgia, most attorneys’ offices are hours away from the town, which has more detainees than residents. Immigrants have no access to email or fax machines and the phones don’t always work. When they do, immigrants must pay for expensive calls to relatives to ask for help finding records to back up their cases.

And that’s also the case in other detention facilities like the Louisiana one where Navas Gómez has his hearing.

The 30-year-old is lucky to have a lawyer who gets a detention officer to scan and email his files in time. The judge steps out to read them, and his hearing goes ahead.

Navas Gómez tells the judge how his captors scalded him with boiling water, leaving a scar, and released him days later in a remote sugarcane field. The judge agrees to consider his case, and nearly a month later, he is granted asylum and leaves the detention center a free man.

“It was truly beautiful, thank God,” he says weeks later, living in Los Angeles.

In this January 6, 2020, photo, Michael Navas Gómez, left, poses for a photo with his attorney, Joshua Greer at his office in Los Angeles. Navas Gómez, who was detained in a remote detention facility in Louisiana for five months, was lucky to have a lawyer who helped him navigate the immigration court system. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes)

Not all are so fortunate. At the Stewart facility in Georgia, a Honduran man who wants to apply for asylum isn’t sure he’ll be able to get the documents he will need to make his case. His mother fled to Costa Rica, and his daughter is here with him.

He asks the judge if there’s way for him to let the court know if he decides before his next hearing that he’d rather just be deported.

Judge Jeffrey Nance tells him he can request deportation by putting a note in a box by the facility’s cafeteria, and he’ll call the man back to court.

The man nods and returns to take his seat in the gallery, his cheeks damp with tears.

***

The stakes are high for those vying to remain in the country. Some want to stay under a provision that opens the door for those without legal papers who have American relatives.

Others, who arrived recently, are seeking asylum to protect them from violence or persecution.

Those hearings are especially daunting, and most asylum seekers don’t win.

The rest are mostly slated for deportation and often have little chance of being able to stay legally in the United State— at least for now.

Their fate often depends on the luck of the draw in a system with extreme disparities from judge to judge. There are judges who reject 99 percent of asylum cases before them; others approve more than 90 percent, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

The Trump administration last year started forcing some asylum seekers to wait in Mexico until the day of their hearings, and families often stay in ramshackle border cities for weeks with their children, with virtually no shot at finding a lawyer. Many of them appear in tent courtrooms on the border that are closed to the public and difficult for lawyers to access.

In El Paso, Texas, immigrants waiting in Mexico show up on the border before dawn and are loaded U.S. government vans and driven to a downtown federal building for their hearings. They appear in courtrooms so crowded the government has barred observers from attending, and immigration detention guards patrol the hallways and escort immigrants on trips to the bathroom.

Immigration Judge Lee O’Connor, who hears these cases in San Diego, snaps at a Honduran mom whose infant bangs on audio devices in court and warns a Salvadoran woman she’ll be at a disadvantage without a lawyer.

“I can’t defend myself because I don’t know anything about the law,” she tells him, sobbing.

Miguel Borrayo, a 40-year-old mechanic who sits before an immigration judge in a courtroom outside Salt Lake City, tried to find a lawyer to help him argue he should be allowed to stay in the country with his American children, despite lacking legal papers.

In this November 22, 2019, photo, mechanic Miguel Borrayo is shown working on a car in Ogden, Utah. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

But he was told it would cost up to $8,000, and he didn’t have a strong case.

So he goes it alone.

Borrayo tells the judge he never had any trouble with the law since slipping across the border from Mexico in 1997 until he turned his car into a McDonald’s parking lot on a family outing for ice cream and came close to a man who was passing by.

The man was an immigration agent. Shortly after pulling into the drive-thru, Borrayo was arrested.

But Immigration Judge Philip Truman spends little time on how Borrayo ended up in his courtroom. He asks about the immigrant’s two teenage children.

Borrayo tells Truman they are both healthy and good students. His 16-year-old daughter dreams of someday becoming a veterinarian. His 13-year-old son wants to become a mechanic, like his dad.

His wife, the teens’ mother, works part-time so she can care for them.

Ironically, this all dooms his case. Truman says it doesn’t seem like his children would suffer tremendously if Borrayo returned to Mexico. Regrettably, he must deport him.

He’s given a month to leave the country—one last Christmas in his family’s home surrounded by snow-capped mountains.

He shrugs off the loss and leaves the courtroom. But days later, he wonders what went wrong.

“I just tried to tell the truth so that they would help me,” he says.

***

The Associated Press’ immigration team sent journalists based around the country to courts from November 12, 2019 to November 22, 2019. Those contributing reporting to the project include:

Philip Marcelo, Boston, @philmarcelo; Sophia Tareen, @sophiatareen, and Noreen Nasir, @noreensnasir, Chicago; Cedar Attanasio, El Paso, Texas, @viaCedar; Nomaan Merchant, Houston, @NomaanMerchant; Amy Taxin, Los Angeles, @ataxin; Kate Brumback, Lumpkin, Ga., @katebrumback; Adriana Gómez Licón, Miami, @agomezlicon; Deepti Hajela, New York, @dhajela; Astrid Galván, Phoenix, @astridgalvan; Brady McCombs, West Valley City, Utah, @BradyMcCombs; Elliot Spagat, San Diego, @elliotspagat, and Colleen Long, Falls Church, Virginia, and @ctlong1.