People wait to vote at a school being used as a polling station during congressional elections in Lima, Peru, Sunday, January 26, 2020. (AP Photo/Martin Mejia)

By FRANKLIN BRICEÑO and CHRISTINE ARMARIO, Associated Press

LIMA, Peru (AP) — A hodgepodge of mostly centrist parties led early results in Peru’s election Sunday to replace the 130-seat congress dissolved by President Martín Vizcarra in his campaign to extinguish pervasive corruption.

Early counts from the National Office of Electoral Processes and a flash poll conducted by international firm Ipsos suggested no party would emerge as a clear victor, meaning Vizcarra will need to build alliances with various factions to break the stalemate with congress that has stymied his presidency.

It wasn’t clear when a full national count would be released.

Early returns showed parties like the re-branded Popular Action and the new Purple Party leading, but with less than 15% of the votes in an election in which 22 parties competed. The party of opposition leader Keiko Fujimori, Popular Force, appeared to slide substantially from its comfortable position four years ago as the legislature’s biggest bloc.

“This is the start of a change,” Lima Mayor Jorge Muñoz, who belongs to the Popular Action party, wrote on Twitter as results came in.

Saludo a todos los peruanos que hoy se sumaron a esta jornada cívico democrática para elegir a nuestros representantes parlamentarios. Se inicia un cambio y oportunidad para comenzar a trabajar articuladamente por un Perú próspero rumbo al Bicentenario.

— Jorge Muñoz (@JorgeMunozAP) January 27, 2020

The South American nation has been roiled by repeated corruption scandals that have eroded public trust in politicians and put some of the nation’s most important leaders behind bars or under investigation.

Vizcarra stunned the nation in September when he invoked seldom-used executive powers to shut down the opposition-controlled legislature, which he accused of shielding crooked politicians and blocking his anti-corruption drive.

The decision plunged Peru into its deepest constitutional crisis in nearly three decades, with anti-Vizcarra lawmakers accusing him of overstepping the law and briefly swearing into office their own president. Nonetheless, the move was widely popular with the public and upheld by Peru’s Constitutional Tribunal.

“The hope of the Peruvian people is to have a different congress—one that can work together for the good of the country,” Jacinto Arana, an evangelical pastor, said as he went to cast his ballot Sunday morning.

The fragmented results were a fresh reminder of the weak state of Peru’s political parties. Some of the biggest winners appeared to be parties that months ago had only a handful of seats in congress. One of those is Popular Action, a center-right party whose heyday is widely seen as the 1980s, when the party’s presidential candidate, Fernando Belaúnde, was re-elected after a military coup.

Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of Peru’s former President Alberto Fujimori, and leader of the opposition party, center, with her husband Mark Vito Villanela, left, arrive to vote during congressional elections in Lima, Peru, Sunday, January 26, 2020. (AP Photo/Martin Mejia)

“No one party has been able to capitalize on the wave of anti-establishment sentiment,” said Abhijit Surya, Peru analyst with The Economist Intelligence Unit.

The lack of a dominant political faction could potentially bode well for Vizcarra if he succeeds in rallying a like-minded coalition.

“We think, on balance, that incoming lawmakers are more likely to work with the executive on a common agenda,” Surya said in a pre-vote analysis. “However, if new elections bring more of the same, it could well put Peru on the path to the kind of instability that has afflicted its neighbors in recent months.”

The 130 new lawmakers will hold office only until scheduled presidential and congressional elections in 2021 and will not be allowed to run in next year’s vote.

Vizcarra rose to the presidency in 2018 after President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski resigned following months of turmoil related to undisclosed financial ties to Odebrecht, the Brazilian construction giant that has admitted to paying nearly $800 million in bribes across 12 countries in exchange for lucrative public works contracts. Peru’s past four presidents are all under investigation.

Adriana Urrutia, director of the political science program at Antonio Ruiz de Montoya University in Lima, said Peruvians are now more inclined to vote for individual candidates than parties that the public has lost confidence in.

“That makes building representative institutions difficult,” she said.

Voting is mandatory in Peru, with a $26 fine for those who don’t participate—about 10% of the monthly minimum wage.

Many voters were skeptical that much will change even with a new congress.

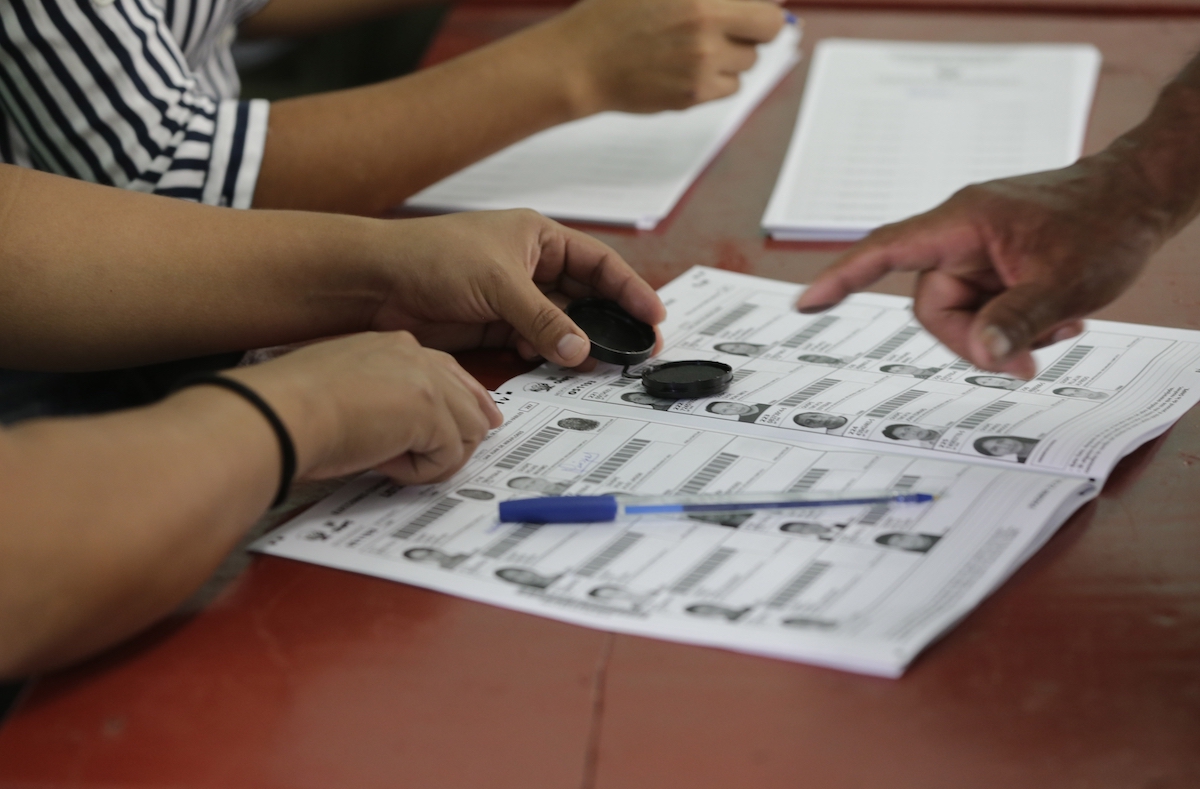

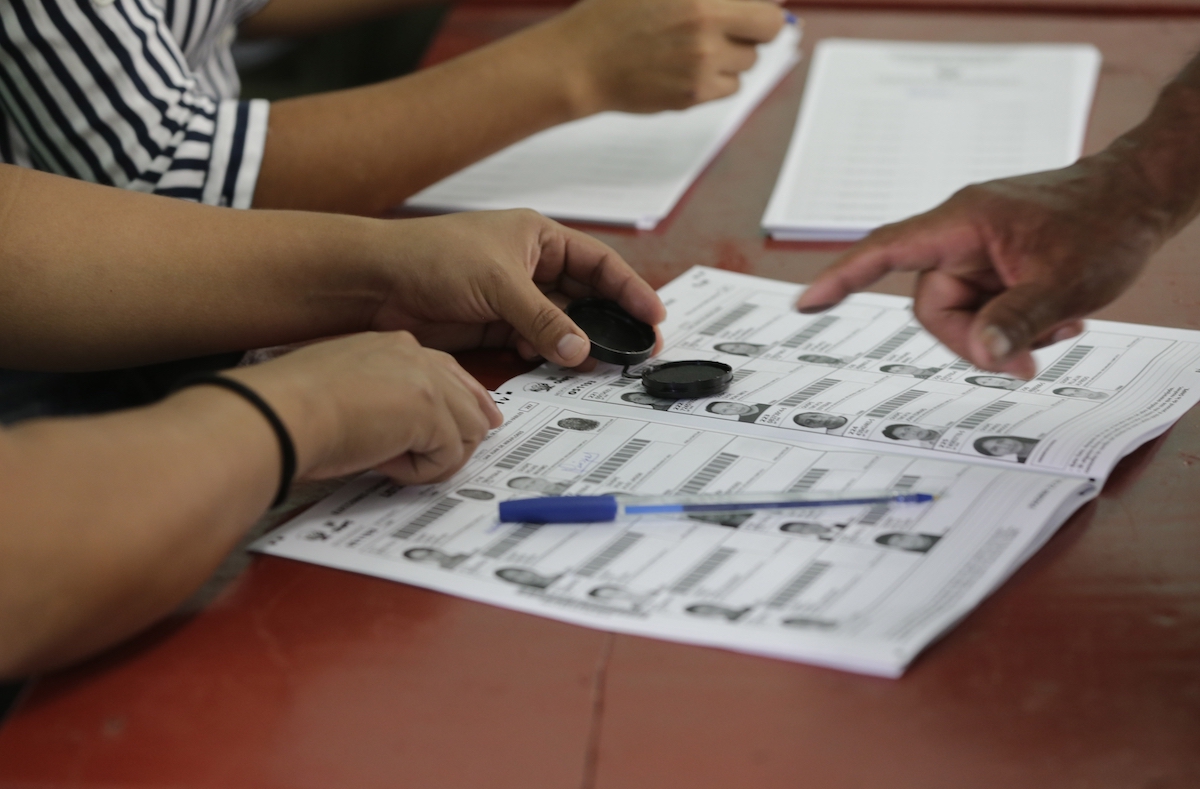

A man puts his fingerprint after vote during congressional elections in Lima, Peru, Sunday, January 26, 2020. (AP Photo/Martin Mejia)

Victor Salazar said he was doubtful that incoming legislators given less than two years in office will have enough time to pass meaningful anti-corruption reforms.

“I don’t have a lot of hope, to tell the truth,” he said as he cast his ballot at a public school in an upper-middle class Lima neighborhood.

Others were putting their hope in electing candidates new to politics and free of the corruption-tarnished history of many past lawmakers.

“This is the best thing the president could have done,” said Arana, the pastor.

***

Associated Press writer Franklin Briceño reported this story in Lima and AP writer Christine Armario reported from Bogotá, Colombia. AP journalists Cesar Olmos and Cesar Barreto in Bogota contributed to this report.