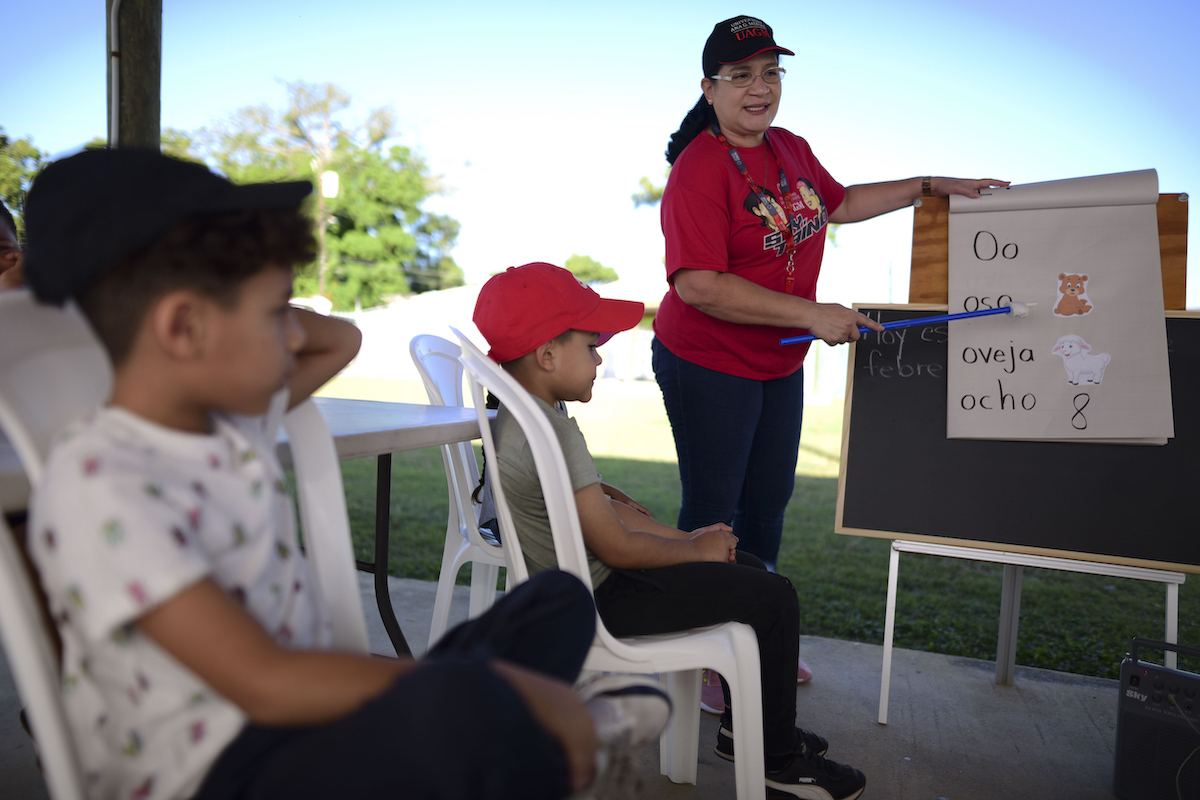

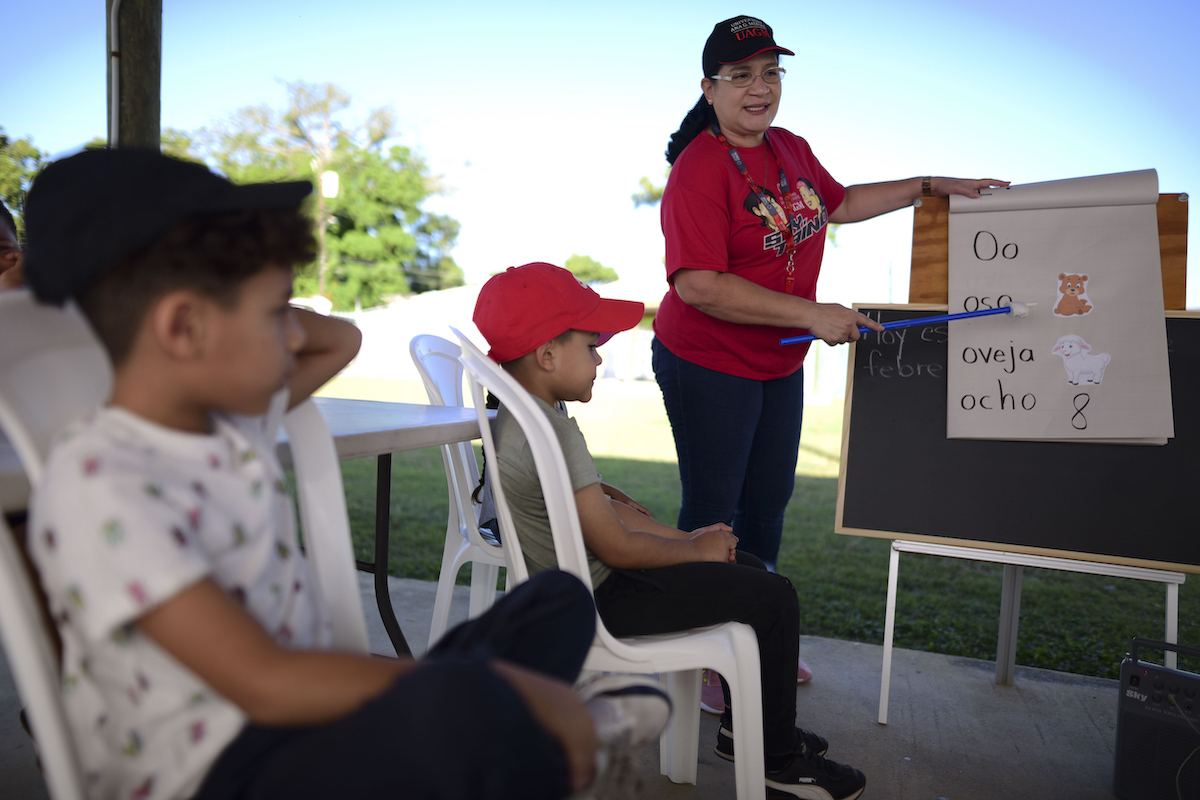

In this Tuesday, February 4, 2020 photo, Martin G. Brumbaugh School kindergarten teacher Nydsy Santiago gives class to her students under a gazebo at a municipal athletic park in Santa Isabel, Puerto Rico. (AP Photo/Carlos Giusti)

By DÁNICA COTO, Associated Press

SANTA ISABEL, Puerto Rico (AP) — Class was about to start when a father drove up to a gazebo that Nydsy Santiago had converted into a makeshift preschool and pulled her aside.

Could she please, he wondered, take his daughter as one of her students? Santiago declined with a heavy heart and explained that she was only authorized to teach her own 23 students, who are among more than 194,000 children in Puerto Rico left out of school nearly a month after a 6.4-magnitude earthquake hit the island’s southern region and forced officials to permanently close dozens of public schools.

“I hope this goes back to normal for everyone,” said Santiago as she chased after papers that the wind blew away on a recent morning.

But few believe that will happen. Classes in this U.S. territory were supposed to start January 9, and while 331 schools opened late as a result of the quake, 61% of the island’s 856 public schools remain shuttered as a growing number of critics blame the island’s Department of Education for the situation.

Mercedes Martínez, president of Puerto Rico’s Federation of Teachers, said it’s unacceptable that no alternatives have been found for children who attend one of the 525 schools that remain closed.

“The government of Puerto Rico has been negligent from the beginning,” she said. “They have not been quick. They have not been strategic. They don’t have a plan on how to start the semester at this point.”

In this Tuesday, February 4, 2020 photo, kindergarten students from the Martin G. Brumbaugh School are led by their teacher to to race track for exercise, leaving behind the gazebo where they are attending class at a municipal athletic park in Santa Isabel, Puerto Rico. (AP Photo/Carlos Giusti)

The situation has led to an increase in homeschooling and prompted some teachers like Santiago to voluntarily find an appropriate outdoor location and resume classes with permission from parents. Santiago began scouting her hometown of Santa Isabel after 19 of 23 parents responded with a range of excited emojis when she proposed the idea last month in a Whatsapp group.

Santiago drove around the southern coastal town and considered holding class in a nearby park until she spotted the swings and cement benches. She eventually settled on a small gazebo near a running track owned by the town whose officials supplied her with plastic tables and chairs and even installed white curtains to block out the sun.

The curtains flew over the heads of her students this week as they painted, swatted at clouds of gnats while they laughed and excitedly pointed to a military helicopter that buzzed past them. Watching the scene from afar was fellow kindergarten teacher Esther Cordero, who shook her head as she criticized government officials grappling with the aftermath of a quake that killed one person, destroyed or damaged hundreds of homes and prompted U.S. President Donald Trump to approve a major disaster declaration.

“They should have invested immediately in trailers,” she said. “And if not that, tarps at least.”

Her colleague, Madeline Cruz, a 37-year-old mother of three children whose school remains closed, nodded vigorously.

“The Department of Education is not paying attention to this,” she said. “There are other alternatives.”

In this Tuesday, February 4, 2020 photo, kindergarten students from the Martin G. Brumbaugh School have class under a gazebo at a municipal athletic park in Santa Isabel, Puerto Rico. (AP Photo/Carlos Giusti)

The complaints over the government’s lack of response echoed those that arose after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico as a Category 4 storm in September 2017, causing more than an estimated $100 billion in damage and killing an estimated 2,975 people in its aftermath.

The women planned to follow Santiago’s lead and hoped to hold classes in other nearby gazebos if they obtained permission from the parents, adding that they were tired of waiting for the government to act.

Eligio Hernández, Puerto Rico’s education secretary, did not return messages left with a spokesman despite repeated requests for comment. On February 2, he announced that another 103 schools were opening this past week.

“This process has been a responsible, detailed and thorough one, since the most important thing for us is the health and safety of all members of the school communities,” he said in a statement.

Engineers have inspected hundreds of public schools, but ongoing strong aftershocks, like the two 5.0 magnitude quakes that struck at a shallow depth in the past two weeks, have forced re-inspections as seismologists warn the shaking will continue for weeks.

At least 69 schools have not passed inspection, and Hernández has said that Holy Week vacation would be shortened to make up for lost time. Education officials also have said that some schools would run two different schedules to accommodate students from other regions while teachers continue to demand answers as to how the situation would be handled long term.

Amid a lack of response from education officials, some parents have opted to homeschool their children, said Nydia Villanueva, who runs a home schooling support group called Amanecer Educativo. She had an informational talk scheduled for early January on the topic but was about to cancel it since no one had signed up. Then the earthquake struck.

“My phone was blowing up,” she said. “In a week and a half, I received more than 240 calls.”

In this Tuesday, February 4, 2020 photo, 5-year-old kindergarten student Ianis Torres Sánchez, from the Martin G. Brumbaugh School, points to letters as she sounds them out in front of her classmates under a gazebo at a municipal athletic park in Santa Isabel, Puerto Rico. (AP Photo/Carlos Giusti)

Among those who called and decided to start homeschooling her two daughters is Mónica Ortiz from the eastern town of Aguas Buenas, where very limited damage was reported. She worries about her eldest daughter graduating on time and the impact the delay of classes has had on her 13-year-old, who is a special education student.

Ortiz said that she hasn’t received any information at all about her daughter’s high school, and was only told that her other daughter’s middle school is not ready to open and it’s unclear when and if it will.

“It’s a good thing they didn’t rush to open schools,” she said. “What I don’t find acceptable is that they haven’t found an alternative.”

In this Tuesday, February 4, 2020 photo, a teacher’s assistant from a Martin G. Brumbaugh School kindergarten class walks amid students attending class under a gazebo at a municipal athletic park in Santa Isabel, Puerto Rico. (AP Photo/Carlos Giusti)

Some of the calls Villanueva received were from parents worried that the ongoing inspections of public schools are only to assess damage, not determine whether they can withstand a strong earthquake or have structural weaknesses such as short columns. Still fresh in many parents’ minds is the image of a school in the southwest coastal town of Guánica whose two top floors were flattened by the quake just two days before classes were scheduled to start.

Marcos Santana, director of Puerto Rico’s Network for the Rights of Children and Youth, said there are plenty of options that don’t require four walls.

“We recognize that it’s an extraordinary situation, but… the Department of Education clearly did not have a plan for this emergency,” he said. “The excuse of not having a building cannot be used for much longer.”