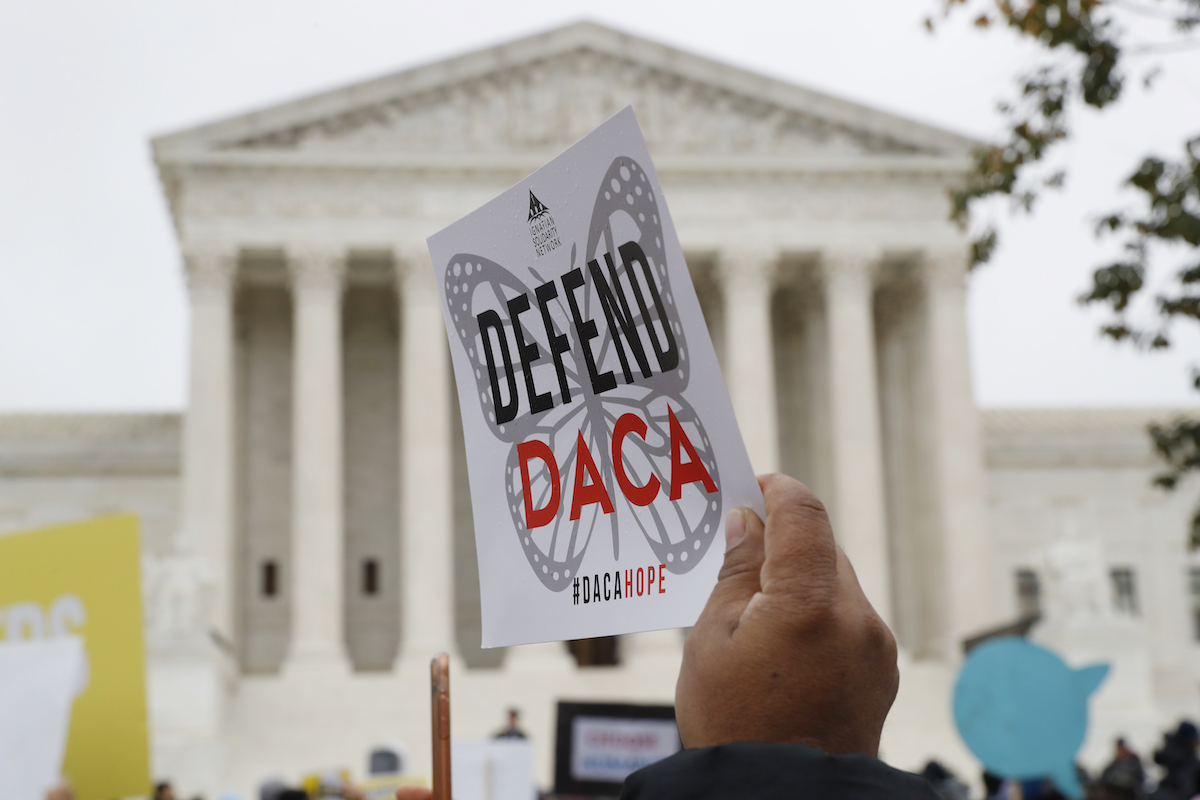

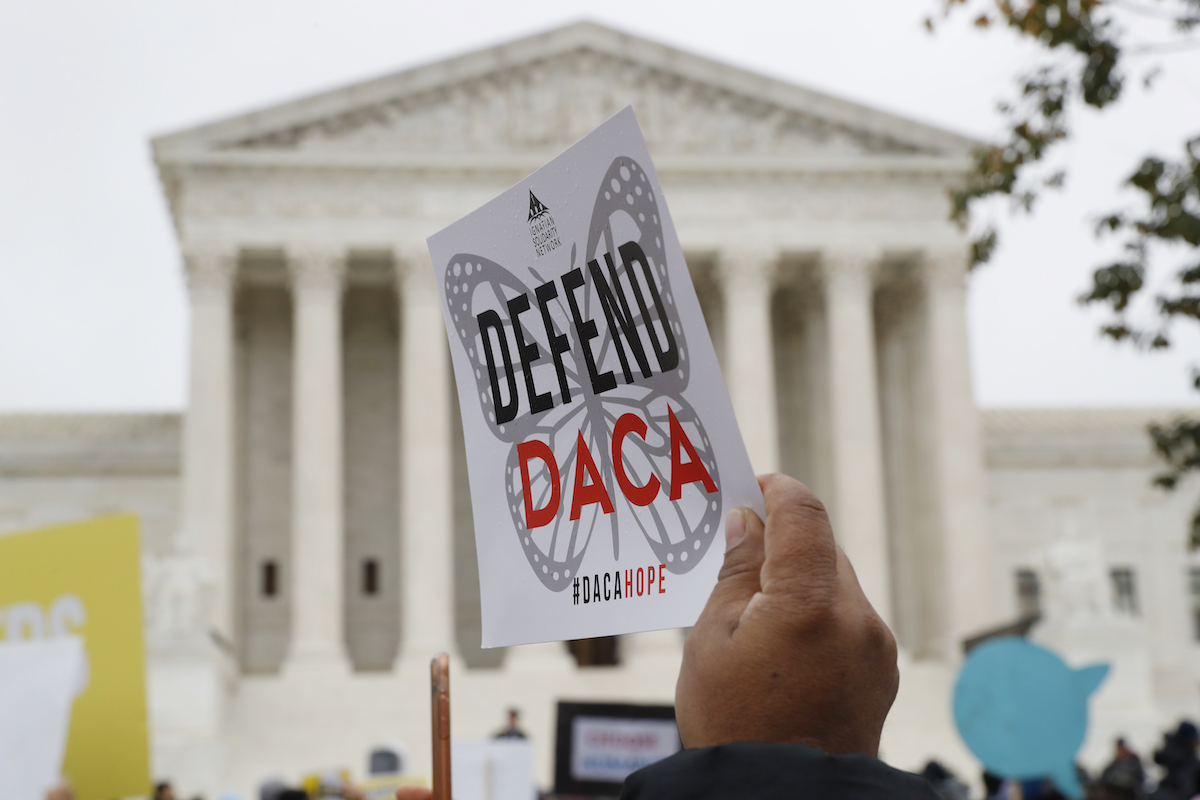

In this November 12, 2019 file photo people rally outside the Supreme Court as oral arguments are heard in the case of President Trump’s decision to end the Obama-era, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA), at the Supreme Court in Washington. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

By ANITA SNOW, Associated Press

PHOENIX (AP) — Tony Valdovinos didn’t know he was in the U.S. illegally until he tried to join the Marine Corps at 18 and learned he was born in Mexico.

Valdovinos, now 29, channeled disappointment into activism, knocking on doors in Latino neighborhoods and registering people to vote, though he can’t cast a ballot himself. He also enrolled in the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program that allows immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to work and protects them from deportation. He now runs a firm helping elect Arizona candidates.

“This is the greatest nation in the world,” said Valdovinos. “I feel a responsibility to serve this country.”

DACA recipients like Valdovinos are assuming prominent roles in the 2020 elections. They are becoming leaders in the Democratic presidential campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Tom Steyer and get-out-the vote groups in immigrant communities, using their shared language and culture to build trust.

Jeanne Batalova, a senior analyst for the Migration Policy Institute in Washington, said political involvement helps DACA recipients facing an uncertain future feel empowered.

“They are doing what they can to exercise their agency, to shape their lives and destinies,” Batalova said.

The campaigns are heating up as the Supreme Court prepares to decide the future of DACA, which President Donald Trump wants to end for the estimated 652,880 recipients. Like many of them, Valdovinos calls himself an American and wants everyone engaged in an election that may shape their future more than any other in their lifetime.

“The current state of DACA is very precarious,” said Arizona Democratic U.S. Rep. Ruben Gallego. “We have to be worried with this administration and this Supreme Court, which are capable of creating a mass deportation of human beings who don’t know any other country than the United States.”

Gallego has long supported DACA recipients, inviting one, second grade teacher Vanessa Mendez, to be his guest this week at Trump’s State of the Union address and recently attending a performance of “Americano!,” a new Phoenix musical inspired by Valdovinos’ life.

Tony Valdovinos speaks during a press conference preview for the musical “Americano!” based on his life Wednesday, January 22, 2020, in Phoenix. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

“We cannot give in to the fear,” Valdovinos said about the upcoming court decision. “We have to fight for the right to have our lives.”

Berkeley, California, journalist and immigrant rights activist Jose Antonio Vargas, who famously revealed he was brought to the U.S. illegally from the Philippines in The New York Times Magazine in 2011, said he identifies with DACA recipients even though he was too old to qualify. Now 39, Vargas discovered his status when applying for a driver’s license at 16.

He said he is encouraged by immigrants like Valdovinos who feel American.

“It’s part of the maturation of this generation, the sophistication of how we tell our stories,” Vargas said. “Many of the DACA recipients are among the most civically engaged Americans you’re likely to meet.”

They include Argentine-born Belén Sisa, 25, Sanders’ deputy press secretary in Washington.

DACA opponents say the program rewards children of families who broke the law. Arizona Republican Rep. Paul Gosar called unsuccessfully for the deportation of DACA recipients who were invited by members of Congress to attend Trump’s State of the Union address in 2018.

Precedents exist for activism by non-voters in the U.S., like the women who fought in the early 20th century for voting rights and African Americans who toppled barriers like literacy tests disenfranchising many black people into the 1960s.

In this September 5, 2017 file photo, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) supporters march in Washington, D.C. (AP Photo/Matt York, File)

The Supreme Court’s conservative majority has indicated it will likely strip DACA protections by June. Liberal justices have suggested the Trump administration has not fully justified its decision to end DACA.

If the court lifts protections, Congress could vote to put the program on surer legal footing. But Congress’ lack of comprehensive immigration reform prompted President Barack Obama in 2012 to create the program that gives immigrants who are in school, graduated from high school or served in the military two-year reprieves on deportation if they don’t commit major crimes.

Trump said in a November tweet that if DACA is overturned, a deal would be made for them to stay, but he also alleged some recipients are “very tough, hardened criminals.”

Acting U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Director Matthew Albence confirmed at a press briefing last month the agency was reopening the closed cases of DACA enrollees “and putting them back on the docket so they can work their way through the immigration courts.”

“Ultimately if the Supreme Court rules that these people do not have a lawful right to be here, it is incumbent on us either to execute the removal orders that were already issued by a judge or put the individual through the immigration court process so we can get a decision from a judge,” Albence said.

Edder Diaz-Martinez, 29, a DACA recipient originally from Mexico City, is communications director for the Maricopa County Democratic Party in Phoenix. Diaz-Martinez called the program a Band-Aid and said recipients need a permanent solution.

This undated photo provided by the Maricopa County Democratic Party shows Edder Diaz-Martinez, communications director for the Maricopa County Democratic Party in Phoenix. (Roy Cruzen/Maricopa County Democratic Party via AP)

Karen Martinez, Nevada state digital director for Steyer, is renewing her DACA status at a cost of $500, not knowing if the program will exist later this year. Now 30, she came to the U.S. from Hidalgo, Mexico, when she was 10.

But if the program crumbles, Martinez said, “I’ll still absolutely feel like I’m an American.”

Valdovinos said he tries not to think about what the court may do, noting that he lived without protections for many years in Arizona while Phoenix-area Sheriff Joe Arpaio oversaw high-profile raids targeting migrants and a state law made police turn over people suspected of being in the country illegally to immigration authorities.

In those years, Valdovinos belonged to Team Awesome, comprised of mostly DACA recipients, who knocked on doors in the heavily Latino district of Maryvale to get Mexican American Daniel Hernandez elected to the Phoenix City Council in 2011.

“The toughest political work is walking in our communities, getting them registered, getting them to vote,” he said. “The absentee ballots come in the mail with the water bill and sit in a pile of papers for years.”

Valdovinos later formed La Machine Consulting F irm to help candidates such as Gallego, Phoenix City Councilman Carlos Garcia and Mayor Kate Gallego with their campaigns.

Fellow Team Awesome member Viridiana Hernandez, who ultimately obtained legal U.S. residency through marriage, said being a DACA recipient helped break down barriers while canvassing neighborhoods.

“I was able to speak to the woman of the house in Spanish, and I’d tell her, ‘Look, I’m just like you, without papers,'” Hernandez said. She then could persuade any U.S. citizens in the family to register to vote.

While Valdovinos couldn’t join the Marines, he said still hopes to gain citizenship.

“It would be so great to cast a vote after knocking on hundreds of thousands of doors,” he said.