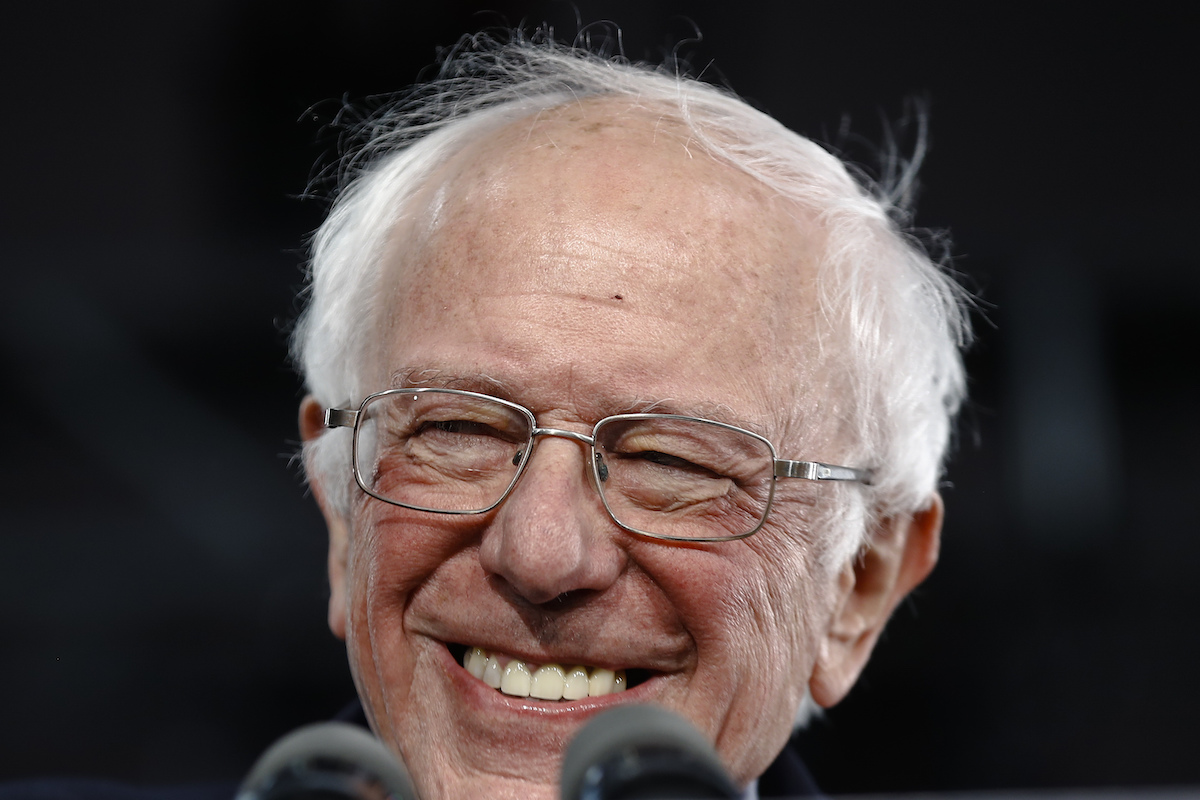

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

LAS VEGAS — I got home around nine from the debate watch party at Make the Road Nevada headquarters last Wednesday. Since the debate had been shown with a Spanish voice-over, and since I was there to observe the party itself and talk to the staffers, and thus hadn’t paid perfect attention to what the candidates were saying, my wife and I climbed into bed to rewatch the show.

We were splitting a bottle of Stella Rosa and a preroll of Blackwater OG—it had been such a long day, including three hours of shadowing a couple canvassers getting out the vote for Bernie Sanders.

“Bloomberg was in the debate for the first time,” I said, pointing to the billionaire’s miserable mug on the TV.

My wife gazed up from her phone and pointed with the joint between her fingers. “Is that Bloomberg?”

“Yup.”

She watched him speak for a second, then, dropping her eyes back down to her phone, shook her head and said, “Nope, no, no, no.”

For most people, picking the president is a gut thing. That said, the gut rarely lies; it’s the brain that’s full of shit. And I’m not being cute either. It’s the truth: smart people think the darnedest things. It has something to do with these self-imposed geniuses placing too much confidence in what they think they know. It’s all too theoretical for know-it-alls. I’m speaking from experience. I can’t count the number of times I’ve argued with my wife on some political or sociological point, bringing all the books I’ve read to bear on my side —everything I think I know about history and economics and philosophy, every classic I’ve read in the literary canon— only to have my wife utter some simple phrase containing an unalloyed nugget of truth, which forces me to disavow my entire position and adopt hers.

I may think I’m smart, but I’m no fool.

***

I did go to the Trump rally last Friday, however. I’d spent all of Thursday typing nearly 6,000 words on the week I’d had thus far—the CNN town hall, canvassing, the debate, the Uber rides, all of it. I submitted my draft at three in the morning and slept like a corpse.

They’d already closed the doors when I got to the Las Vegas Convention Center, 15 minutes before the rally was set to start (at noon). People were streaming back across the street toward the parking lot, either carrying the Stars and Stripes or wearing clothes printed with it. I decided to pay the 10 dollars for parking anyway, since they were showing Trump’s address on a jumbo screen out front, where a crowd was gathering for a mini rally outside the main one.

With almost two million square-feet of space, the Convention Center is the city’s biggest draw besides the casinos. (I’ve been inside the Convention Center once before, for the Mr. Olympia bodybuilding competition—as a spectator, obviously.) It took me nearly five minutes to walk around to the front of the building where the mini-rally was being held, off Paradise Road. Along the way I passed vendors hawking Trump paraphernalia—hats, some with orange hair sticking out the top as an homage to the President; t-shirts; flags; sweaters; scarves; banners. Most of the vendors I saw were black, but I didn’t judge them: everybody has to earn a buck somehow, and your options for earning an honest dollar are drastically reduced the darker you happen to be. There was also a taco truck, a Chinese food truck named The Great Wall of China, along with a BBQ truck and a couple others.

#trump2020 at the Line for Trumps rally in Vegas pic.twitter.com/xyiU8NGk1K

— Pam Political (@pbarrie3) February 21, 2020

As I rounded the corner out front, I caught the distinct tone and cadence of the Thing’s speech, reverberating from the loudspeakers up ahead. In front of the TV, which was set up near the main entrance, there were at least a thousand red hats, each with a pale body attached underneath. There were a few dark bodies, too, sprinkled here and there. I spotted a trigueña wearing a blue Puerto Rico jersey. She clapped to everything Trump said, laughing at every joke he made.

Trump spent most of his two-hour speech trolling—the Democrats (“Pocahontas” and “Mini Mike”), Obama, the “fake news” at the back of the hall, Hollywood, Brad Pitt, South Korea, the owner of Comcast. This chubby kid with his girlfriend kept giggling at every punchline. You would’ve thought Trump was tickling the dude’s balls by the sheer titillation in his voice. The kid couldn’t get enough of it.

“Trump’s the funniest president ever!” he told his girlfriend, who never said anything.

Half an hour later, in another part of the crowd —I try to be a moving target in certain situations— I heard another guy, this one the jock type, say, “He’s hilarious!”

Joe Rogan and other comics have pointed out how Trump is more like one of them than a politician. As with comics, Trump has bits —material he works out in front of different crowds— only, unlike a comic, who tests his jokes before a wide variety of people, Trump tries his new material in front of audiences of the faithful who already adore him, keeping whatever gets a laugh and chucking whatever falls flat.

Trump is the consummate demagogue.

As any experienced comic will tell you, though, honing your material only in front of like-minded audiences is a sure way to become a horrible comic. That’s probably why Trump is actually a terrible politician, if you look past the facade of his popularity.

Trump Rally, Las Vegas pic.twitter.com/ToMyGyYJPZ

— Nicole Lewis (@NicoleL33399295) February 21, 2020

Take the Vegas rally, for instance. All those people at a packed Trump rally seems impressive, until you remember that 1) Nevada went for Hillary in 2016, 2) the state elected the first Latina senator in U.S. history —a Democrat— also in 2016 (the year Trump’s name was on the ballot), and 3) in 2018, Nevada replaced its Republican governor with a Democrat and elected yet another female Democratic senator, making the Silver State one of five in the Union to be represented by two female Democrats in the Senate. So Nevada isn’t Trumpland—though his biggest sponsor, the billionaire casino magnate Sheldon Adelson, “happens to own the paper,” the Las Vegas Review-Journal, as Trump pointed out at the rally. Mr. and Mrs. Adelson were even in attendance, seated in the VIP section.

Still, in the last few years Nevada has gone from purple to blue, thanks in no small part to all the newcomers from neighboring California and the faraway Midwest —I meet a lot of fellow Chicagoans out here—plus the state’s growing Latino population, which currently represents 29 percent of all Nevadans.

Pretty soon a majority of Nevadans will be pronouncing the state’s name Ne-vah-dah, how it should be.

Leave it to Anglo invaders to steal a piece of Mexican land and then impose some foreign pronunciation of its name—the “foreign” here being English. I know folks like Senator Klobuchar are itching to pass a nationwide English First law, to preserve American (Anglo) culture. But according to Nevada history, it’s Spanish first —or the indigenous Numic languages first, actually— and English last of all.

But I digress. After all, a lot of people in this country have short memories by choice, so I won’t waste everyone’s time with a history lesson.

That I never clapped at the Trump rally, not once, made the people around me nervous. Whether because I’m brown, grew up poor, or both, I’ve developed the ability to pick up the mood around me, specifically the attitude of strangers toward me. It’s a matter of personal safety, if not survival. When I didn’t scream “U-S-A! U-S-A!” the half-dozen times the chant was raised, when I failed to applaud as Trump ran through his dirty laundry list of supposed achievements —the “booming” economy, all the “good-paying jobs” he’s created, his “big, beautiful wall” along the southern border— I felt a pall fall over the people in my immediate vicinity. That I kept punching stuff into my phone raised the temperature even more. And though I wasn’t the only brown person in the audience —there were a few, like I said— I was the only young brown guy there who looked like me and was dressed the way I was, if you know what I mean. Plus, when I wasn’t tweeting my notes and observations, I kept my arms crossed.

I could tell the people around me were increasingly wondering why I was there.

A wiry grey-haired lady wearing the U.S. flag somewhere on her —there were so many U.S. flags everywhere, it’s all a red-white-and-blue blur —anyway, the lady came by with a clipboard and asked if I wanted to sign a petition to stop “our Communist governor” from raising taxes on gasoline. “I actually agree with him,” I told her. “But thanks anyway.” Man, you should’ve seen the look on her face, as if I’d told her I ate my boogers. I’m sure she ratted me out to the string of attendees next to me, telling them I was a Commie or at least a pinko—I could’ve sworn I caught her out of the corner of my eye pointing me out or otherwise making gestures toward me.

My wife Gia is at Trump rally here in Vegas representing our new “Democrats for Trump” group. Here’s a photo she took of another group of supporters the media doesn’t want you to know about… pic.twitter.com/qxpFeYflM6

— Chuck Muth (@ChuckMuth) February 21, 2020

Come to think of it, Nevada is still a cowboy state, so who knows how many guns were around me at that Trump rally. It only takes one Fox News fanatic to see me as an existential threat to his god and country…

GOD GUNS & TRUMP read a t-shirt on sale. I wish I knew the difference between the Party of Trump and ISIS, or Al-Qaeda, or Hezbollah—and don’t say one’s Anglo Christian and the others are Arab Muslim, because I’m none of those things, so it makes no difference to me which group wants to impose its racial-religious bullshit on me through at least the threat of violence.

A placard at the rally read TRUMP + CAPITALISM = FREEDOM!!!—which sums up pretty nicely the absurdity of American fascism: that a president who puts kids in cages and wants to deny women the right to control their own bodies, and a system that treats people as slaves fit only for production and consumption, should be the two pillars of human liberation.

The standard would be to go through the rest of my notes from the event, but who doesn’t know what a Trump rally is like, more or less? We all have either been to one (I’ve been to a couple now), or watched video of one, or at least know a Trump supporter and can extrapolate from there. There are a lot of white people at these gatherings, mostly in their thirties or older, and very patriotic, at least in their minds—in the rest of ours, a lot of them are really just white nationalists.

I’ll just say, though, that I always leave a Trump rally feeling a little more optimistic. Once you get up close to the Beast and see what it really is, you realize that many Trump supporters are merely as afraid of the future as the rest of us are of them. They see the face of the country changing, and how its culture is changing with it. They see how ascendant black pop culture has become, thanks to music and sports —the two most important forms of entertainment in this country —to the point where, in the most inhabited areas of the country, and especially among the youth, pop culture and black culture are virtually synonymous. Jay Z and Dre are both billionaires; Oprah’s still the most popular woman in America; any black rapper, athlete or celebrity work his check has a home in some of the most exclusive neighborhoods in Southern California; and every boy, no matter the color, still wants to be like Mike—”any one: Tyson, Jordan, Jackson…“

Then there’s Obama, the most popular president since Reagan, with a Nobel Peace Prize and everything. The Obamas are still popular, lauded nearly everywhere they go in the world, more so than the actual First Family, or any of their living predecessors.

Heading to represent California at Vegas TRUMP rally!!! pic.twitter.com/qVHtXqKv4Z

— John Vaughn (@Coolimagejohn) February 21, 2020

And now there’s Latino culture, coming round the corner.

All these changes make a white person who believes this country was founded as an Anglo Christian country, and that Anglo Christian culture should be its most dominant feature by far—all this diversity and multiculturalism makes such a person very afraid. And because fear is an ugly feeling, their fear makes them angry at the objects of their fear—so mad, in fact, that they just might get the urge to shoot up their school, or a black church, or their local Walmart.

Name me a mass shooter —a terrorist— who was Latino or black. I’ll wait…

They like to say it’s the colored folks who are violent. Yet, considering how abused and exploited the brown and black people of this country have been —and how long— if anything, brown and black people have proven to be supremely peaceful. You might even say Christ-like.

Or maybe they just don’t have enough power to fight back. Maybe that’s what Trumpism is about: making sure the brown and black people never gain the power to defend the portion of this country which is rightfully theirs.

Power does what power can, no? Or is true power shown through restraint?

Anyway, so much for Trump rallies.

***

My Democratic presidential caucus was held at Del Webb Middle School in Anthem, a “master-planned community” on the south end of the Las Vegas Valley, right next to Seven Hills, where “Iron” Mike Tyson, and the current heavyweight boxing champion Tyson Fury, keep their mansions.

I woke up to grey skies and rain. It’s never grey in Vegas, much less rains, except by accident. That it was raining on Caucus Day, of all days, was too much of a coincidence to accept, like accidentally being run off the road by two FBI agents in an unmarked car. I just knew in my bones that the Anti-Democratic National Committee was behind the sour weather somehow—they were doing everything in their power to keep the flaky youngsters who support Bernie from showing up! How diabolical! They must have hired the same guys who seed the clouds over Dubai to shower the city every Tuesday.

Del Webb Middle School sits on a raised plot of land, with four tennis courts, four basketball courts, a baseball diamond and a green field. I dodged puddles as I ran inside the back doors leading into the courtyard—most schools here have courtyards with benches, tables and palm trees. A few tables were set up in the foyer: one for the Bernie campaign, one for Warren, one for Buttigieg, one for Biden. A line had already formed with 20 or so people waiting to get into the cafeteria, where the registration would take place from 10 till noon, when the actual caucus began.

I was wearing a fresh Bernie 2020 t-shirt under my blazer, to make it crystal clear who I’d shown up for. Most people wore pins and stickers from the various campaigns—I’d say one in five were fellow travelers for Bernie, but I wasn’t counting. Mayor Pete had a big turnout, possibly the largest of any other campaign (one Pete guy wore jeans and thong sandals, in the rain).

They didn’t let us into the cafeteria till about 10:15 or so. There were collapsible tables set up in a row, each with a range of letters: A-C, D-H, I-M, and so on. (I noticed the sports teams at the school were known as the Wranglers, which made Webb the appropriate choice for a caucus.) We were told to check in alphabetically by our last names. My name wasn’t on the list—it went straight from Akerman to Alberts. “This list is updated as of January,” the middle-aged volunteer lady seated behind the table told me. “You sure you’re registered?”

“Positive.”

“Well, you’re gonna hafta go over to the registration table. They can help you there.”

At the registration table, another middle-aged lady told me to re-register on her iPad. I filled in everything, pressed submit, and got an alert indicating I was already registered—like I knew I was. This stumped the lady, who tried getting help from the woman next to her who was already dealing with someone else. Then another middle-aged lady —it was like a bungled bake sale in that cafeteria— came over and said something was wrong with the system, that they hadn’t received everything they needed in their kits, and that we would be getting around the issue with an impromptu “voter registration thing,” a sheet of paper where they crossed out the labels printed on it and wrote in new ones: Name, Registration No., and Sticker No. (The Name bit was redundant: I watched one of the ladies cross out the word Name already printed on the sheet of paper and write Name just above it.) We were to initial at the end of the row containing our information, confirming that the numbers matched the ones on our caucus ballots.

I spotted Julio from Latino Rebels loitering by the main doors leading back out into the courtyard. He was in town for the day to make two appearances on MSNBC with Ali Velshi, one in the morning, one at night. With his first appearance over, and the other outlets closely following the culinary workers’ caucus at the Bellagio, Julio decided to take a 30-minute cab ride from the Strip down to Anthem to observe this bougie caucus in action.

My precinct, Precinct 1513, was assigned to Room 220, across the courtyard. There were only a handful of other people in the classroom—a middle-aged couple caucusing for Buttigieg (the wife was the precinct captain for Pete) and a few people for Biden, one of them the precinct captain. The Biden gang would be the biggest in the room, and the most organized, followed by the people for Pete. Julio threw me off by mentioning how I was the only Bernie supporter in the room thus far. “What if Bernie isn’t viable?” he whispered in my ear, a big grin on his face. “What if you have to join up with someone else?”

I hadn’t thought of that. Because I’d been talking to Bernie people from all over Vegas for the past few years, and had just spent the week on the pro-Bernie east side of the valley, I assumed Bernie supporters would show up at my caucus in numbers, too. But as the room began filling up with other caucus-goers from my precinct, mostly for Biden and Buttigieg, some for Warren, I started getting nervous. If somehow Bernie weren’t viable, I figured I would go with Warren; but if she weren’t viable either—and it was looking like she wouldn’t be—what would I do then? I wasn’t going to team up with Biden or Klobuchar. So… Buttigieg? After everything I’ve said about the man and what I think he really stands for?

This lesser-of-two-evils method of voting is evil in and of itself.

Julio was relishing the prospect of me having to squad up with my bête noire. “Oh, that would be too good!”

I thought of telling everybody in the room that Julio was secretly a Trump infiltrator, there to sabotage the proceedings—anything to get him out of the room, so he wouldn’t witness what I might be forced to do for the sake of keeping the New Nazis from fully conquering America.

When a 20-something Indian kid came in with his father and sat in the chairs behind us, I saw a ray of hope.

“You think they’re for Bernie?” Julio whispered.

“Hey, who you guys voting for?” I asked them.

The kid gave me a cool smile. “Bernie,” he said. “You?”

I turned so he could see my t-shirt.

“Nice,” he said, nodding.

I chatted with the Pete precinct captain and her husband, a 50 or 60-something couple from San Diego, and Georgia before that. They had never caucused before, same as me (I moved from Illinois after primary season in 2016). They were excited to take on such a direct role in the democratic process—all us caucus-goers were, which is why we’d shown up to a middle school at 10 on a rainy morning. There was an instant camaraderie from the fact that, despite our separate backgrounds, and our different politics and visions for America, we were all Democrats —all against Trump and the Republican Party— and we all believed in the duties of citizenship in a democratic society.

Our temporary precinct chair, who turned out to be the same woman from the registration table, came in to let us know that the caucus would be starting in 15 minutes, and that there were to be no signs, stickers or any other campaign materials posted anywhere in the room. While we waited, Julio and I talked about political documentaries. “You gotta watch this McGovern one,” he said. “One Bright Shining Moment… Have you seen Edge of Democracy?” I added both to my expanding list of stuff people tell me I “gotta watch.”

Things weren’t exactly kumbaya in the room. People would come in and sit with their fellow supporters, the tension building as the room filled, the people of one group eyeing those in the other groups somewhat suspiciously. Human beings are tribal to our core: no matter the game, people want badly for their team to win. I guess that instinct is what allowed us to emerge from Africa and spread across the face of the planet, but now that we have, our tendencies to divide ourselves up and compete with one another are becoming more of a hindrance to our further development—-you could even say they pose a threat to our very survival as a species.

Only together will we go far.

A smartly dressed brown guy came in and introduced himself as Gabriel from the Bernie Sanders campaign in California. He was there as an observer, to make sure things didn’t go sideways like they had in Iowa. He rounded up the people caucusing for Bernie —there were six of us— and had us sit in a semicircle of chairs at the back of the room. In private Gabriel told us Bernie people not to fret about our meager numbers in the room, that we could expect a boost from the early-voting returns. That news put us at ease—surely the Bernie campaign was so organized that most of his supporters had flooded the polls during the four days of early voting the weekend prior; we six were just bringing up the rear.

Gabriel said he was going to check on the other precincts in the other rooms, but would be back soon. In the meantime, we Bernie people got to know each other. The white kid on my left wore glasses and looked like the cynical gamer type, leaning back in his chair, arms crossed, huffing at what he overheard from the other groups. Like me, he couldn’t stand Buttigieg. “I don’t get it,” he said, sneering over at Pete’s gang with their blue and gold pins and stickers. “Don’t they see how full of shit the guy is?”

To my left sat Michael, the Indian kid, with his gray-haired father seated to his left. “He dragged me here,” the old man said, smiling—he was just happy to be with his boy.

Michael told us he worked “with a bunch of Republicans” over in Summerlin.

“You ever been in those country clubs?” asked Josh, a pale thin kid who looked of Eastern European descent. “I clean pools there, and the houses are so nice!”

Michael recognized Tyler from somewhere, the white kid sitting between Mike’s dad and Josh. It turned out Michael and Tyler went to Coronado High School together, but they only knew each other through mutual friends.

We were sweating about how much of a boost we’d get from the early-voting returns, when Gabriel came back in the room. There was only one bit of business left to take care of—-who would be our precinct captain? Each group also had to elect someone to deliver a one-minute speech in favor of its candidate to the whole room. With our low number, it was assumed that whomever we picked as precinct captain would also be the one to give the pitch. I guess since I was wearing a Bernie t-shirt and blazer, and had been chatting everybody up, Gabriel nominated me for precinct captain. I turned to the other five in the group to see what they thought. They all nodded, and it was settled.

I was to take pictures of the caucus sheet when all was said and done, and text it to Gabriel, who gave me his number and asked for mine.

Alone in his group, this old guy caucusing for Tom Steyer wandered the room, chatting with the different supporters. He came over by us Bernie people, a Steyer sticker stuck to his forehead, and started probing us: “You know Bernie isn’t going to do everything he’s promising to do.”

“Oh, I know,” I said. “Look, the Senate is still controlled by the Republicans, right? As is the Supreme Court. So we just need a force in government pulling hard in the opposite direction, and we’ll meet somewhere in the middle.”

“That’s a good point,” said the old man, lifting his fore finger and nodding. “I take it, though, none of you like Tom Steyer.”

“I like Steyer,” Michael and I both said, the rest of the group nodding. “I like what he’s been saying,” I said. “About social and economic justice. About environmental justice. About the criminal justice system.”

“But he’s a billionaire,” the old man pointed out.

“Yeah, I know. But I read about how he started a nonprofit community bank.”

“That’s right!” The old man seemed impressed that I actually seemed to know a few things about the Steyer campaign, and that I could appreciate what Tom did with all that wealth of his, trying to give back and all.

The old man started saying something else, but the precinct chairwoman had come back in the room and was calling the caucus to order.

She began with a few formalities, letting us know how the caucus would proceed, and that the process was open to Democrats of all colors, ethnicities, nationalities, creeds, religions, genders, sexual orientations, economic statuses and philosophies. It ended with her nominating herself for permanent chair of Precinct 1513—she said she was from the precinct herself, too—and, since she’d already been running the show from the start, and no one wanted to waste any more time or energy than we already were, the room approved the motion unanimously with a simple “Yes” vote.

And the Caucus for Precinct 1513 begins. #NevadaCaucuses pic.twitter.com/lpEza3hl3E

— Julio Ricardo Varela (@julito77) February 22, 2020

The observers in the room (Julio the journalist and a young woman who was working for Edison Research) were made to sit along a wall, out of the way. Then the precinct chair physically counted every caucus-goer attendance. We were made to lift our ballots and only lower them as she counted us off. There were 34 caucus-goers in our precinct—which we all confirmed, again, by a “Yes” vote.

Then she looked up the early-voting returns for our precinct on her iPad and read the number: 66. That meant our precinct had a solid 100 caucus participants, earning a hearty round of applause from the room, as though having a perfect hundred somehow proved we were special.

Each candidate needed 15 percent of the vote in each precinct to be viable—so in our precinct that meant an easy 15 votes, hence the applause for simple math. Our precinct would elect 10 delegates to send to the Clark County Democratic Convention in April.

Next the chairwoman counted the members of each group. Biden had 11 caucus-goers in the room, Pete had seven, Warren had six (same as Bernie), Klobuchar only had three (a married couple and someone else), and Steyer just had his one quirky but friendly old-timer. Then the early-voting results were reported: another 11 for Biden, 22 for Buttigieg, seven for Klobuchar, 15 for Sanders, four for Steyer, and another seven for Warren.

After the first round, the situation stood as so: Biden, with 22 votes, was viable; so was Pete, with 29; so was Sanders, with 21. With 13, Warren was just two votes shy of viability, but Klobuchar (with 10) and Steyer (a measly 5) were done for.

Now came the speeches.

A tall silver-haired man stood up to give the pitch for Biden, talking up Joe’s electability, his experience in the Senate and the White House, and his popularity in the Rust Belt states. Next, the woman who was Pete’s precinct captain stood up to sell us on Buttigieg, saying that Pete gave her the same feeling that Obama had back in ’08.

Then came my turn.

When I stood up, my mind went blank. What could I tell my fellow precinct members about Bernie? “Well,” I said, “we all know Bernie’s the frontrunner—clearly. He won Iowa. He won New Hampshire. He’s gonna win Nevada. He’s gonna win Texas, and California. This is a movement. And I know people are afraid Bernie’s going to implement some kind of radical socialist agenda, but let’s be real. The Senate and the Supreme Court are still controlled by Republicans. So all we need is a progressive force pulling in the opposite direction. And Bernie arguably has the most consistent record in politics. He’s been fighting for the same thing since before my mother was born, since the sixties.”

I kept saying things along those lines, when the chairwoman called time, at which point I politely asked everybody to join up with Bernie, and sat down.

I honestly and truly hate public speaking—which is a main reason why I write.

“Good job, man,” Michael said, leaning over to tap me on the shoulder. I didn’t believe him, but I thanked him anyway.

Here’s where everybody got up and the people whose candidates weren’t viable heard arguments from those who were about why they should join up. I’d had my eye on that old-timer for Steyer. He was friendly and seemed receptive to Bernie’s message—his only concern was that, as someone in his third act, he didn’t want some president completely scrapping the current healthcare system and replacing it with something new and untested.

“I don’t want to worry about health care either when I’m your age,” I told him straight up. “So do me a favor, do us a favor”—Michael was making the case for Bernie with me—”join Bernie so we can get this done once and for all.”

A little convincing the Steyer supporter to come to other viable candidates. pic.twitter.com/VXtlpmXuUH

— Julio Ricardo Varela (@julito77) February 22, 2020

“You make a good point. And I do like Bernie. But he’s already viable.” The old man was considering joining the Warren group, which needed only two more votes to get back in. I couldn’t really blame the old-timer—it feels good to be needed, especially at his age.

“Well, think about it,” I said. “Okay, sure,” the man said, nodding and waving me off with a wrinkly hand. He was already being courted by Warren’s precinct captain.

Michael and I went over to see what was happening with the rest of Warren’s people.

My opening line didn’t go over so well: “Face it, Warren and Bernie are the two candidates on the left wing of the party. So if Warren’s not viable, you gotta come over to Bernie.” This peeved the middle-aged ladies in the group, who hardly laid eyes on me, even as I stood before them and made my case for Bernie. One woman huffed, shaking her head, her arms folded. Warren’s people wanted nothing to do with Bernie—they were hoping to become viable by recruiting Klobuchar’s people and that one Steyer guy. In the end, they won over the old man and one Klobuchar voter. With the one vote they gained from the realignment of early-voting preferences, that gave Warren 16 votes, thus making her viable.

Bernie had picked up another from the realignment, as well, giving our group 22 votes. The Klobuchar couple had split up, one going over to Biden and the other going over to Pete, and after the realignment of early votes, that left Biden with 26 votes and Pete with a hefty 36.

Since there were 100 total participants in our precinct, and of those we needed to elect 10 delegates for the county convention, it was a simple matter of dividing each vote count by 10 to get the number of delegates each candidate would be allotted: Biden, 2.6; Pete, 3.6; Bernie, 2.2; and Warren, 1.6.

The usual rounding up or down—3 + 4 + 2 + 2—would’ve given us 11 delegates, one extra. So one of the three candidates tied with .6’s would have to lose a delegate. (At first, someone who didn’t understand the numbers suggested that Bernie might have to lose a delegate, to which I said, “Oh, no he won’t.”) To settle the issue, a deck of cards was brought out: the group that pulled the lowest card would lose a delegate. The Warren group pulled a 4, Buttigieg pulled an 8, and Biden pulled a jack—so Warren lost a delegate, bringing her total down to the loneliest number: 1. The rest of the final delegate count came out four for Buttigieg, three for Biden, and two for Bernie.

This is the finally tally out of Precinct 1513 #NevadaCaucus2020 #NevadaCaucuses

Delegate tiebreaker with a draw of cards led to Warren losing a delegate here.

Warren was also non-viable in first round but then was viable with Pete, Biden and Bernie. pic.twitter.com/cqspj5Wa9h

— Julio Ricardo Varela (@julito77) February 22, 2020

The news from the culinary workers’ caucus at the Bellagio was that Bernie and Biden had been the only viable candidates, Bernie with 76 votes after the final round, Biden with 45, and two votes left uncommitted. I’m curious to know where those two uncommitted votes came from, whether from the six in-person votes for Warren in the first round or the three votes for Steyer. If it was any of Warren’s people, I swear…

***

The caucus now over, all that was left was to choose the delegates and the alternates from the people in attendance. Since I’d already had the honor of being precinct captain for Bernie, I declined the group’s invitation to be a delegate or an alternate—truth is, really, I’d already gotten way more involved than I wanted to be. We chose Tyler and Josh as the delegates bound for the county convention in April, with Michael and the gamer serving as alternates. We all exchanged numbers. I took a picture of the caucus sheet taped to the blackboard, showing all the final numbers, and texted it to Gabriel.

I shook hands with the Bernie gang, and left with Julio.

Later that night, my wife and I met Julio at Paris, where he was making his second appearance of the day on MSNBC. They were filming up in the nightclub, Chateau, nestled underneath the hotel’s glittering half-sized replica of the Eiffel Tower, directly across the Strip from the Bellagio’s iconic fountains. My wife and I ordered a couple of Blue Moons and watched a cover band performing hits on the little stage at Le Cabaret, with its big velvet curtain, bistro tables under the leaves of a fake tree, and a small dance floor packed with older couples and young single girls trying to live it up.

My wife was watching this old Asian couple, who were doing all sorts of random moves—sometimes flapping their arms, other times gliding elegantly around in swirls, as if they were competing on Dancing with the Stars. “I bet they’re tourists,” my wife said. She was smiling at them.

“Of course they are. They’re in Vegas having the time of their lives.”

The main singer in the band was this 50-something Asian man who kept his shades on the whole tim, but he was smooth, a charmer, and the audience loved him. He was Bruno Mars, if Bruno never made it. He shared singing duty with a thick Asian woman, about 40, who sang like Fergie, yet she barely knew enough English to rap with the main guy between songs, mostly smiling and doing her best to be affable. But when she sang, she knew every word—you would’ve thought she was American born and raised.

Julio came down at 10.

“I loved being at that caucus today!” Julio was saying. “That was real democracy!”

That’s exactly what it was —old school, Athenian-style democracy— and Bernie had won the state of Nevada in a landslide, with 46.8 percent of the vote, compared to Biden’s 20.2 percent and Buttigieg’s lousy 14.3.

This is a movement. I was right. Too bad the Warren people didn’t realize that when they had the chance.

***

Hector Luis Alamo is the Editor and Publisher of ENCLAVE and host of the Remember the Show! podcast. He tweets from @HectorLuisAlamo.

did you ever think that calling the president a thing or white people pale is what makes so many dislike you.

[…] which held its last caucuses in late February 2020 before switching to the primary system, is the third most diverse state in the country, with a […]