President Donald Trump listens to a question during press briefing with the coronavirus task force, at the White House, Wednesday, March 18, 2020, in Washington. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

Editor’s Note: An previous version of this opinion piece was published by Common Dreams. This version was edited by Latino Rebels to reflect new data from Thursday evening. LR also added a clip of President Trump’s Thursday press conference. The author gave us permission to publish this piece.

After weeks of denying the threat of COVID-19, the scale and spread of the pandemic has made it impossible for President Trump to continue denying the problem as a political “hoax” perpetrated by his political opponents to bring him down in November.

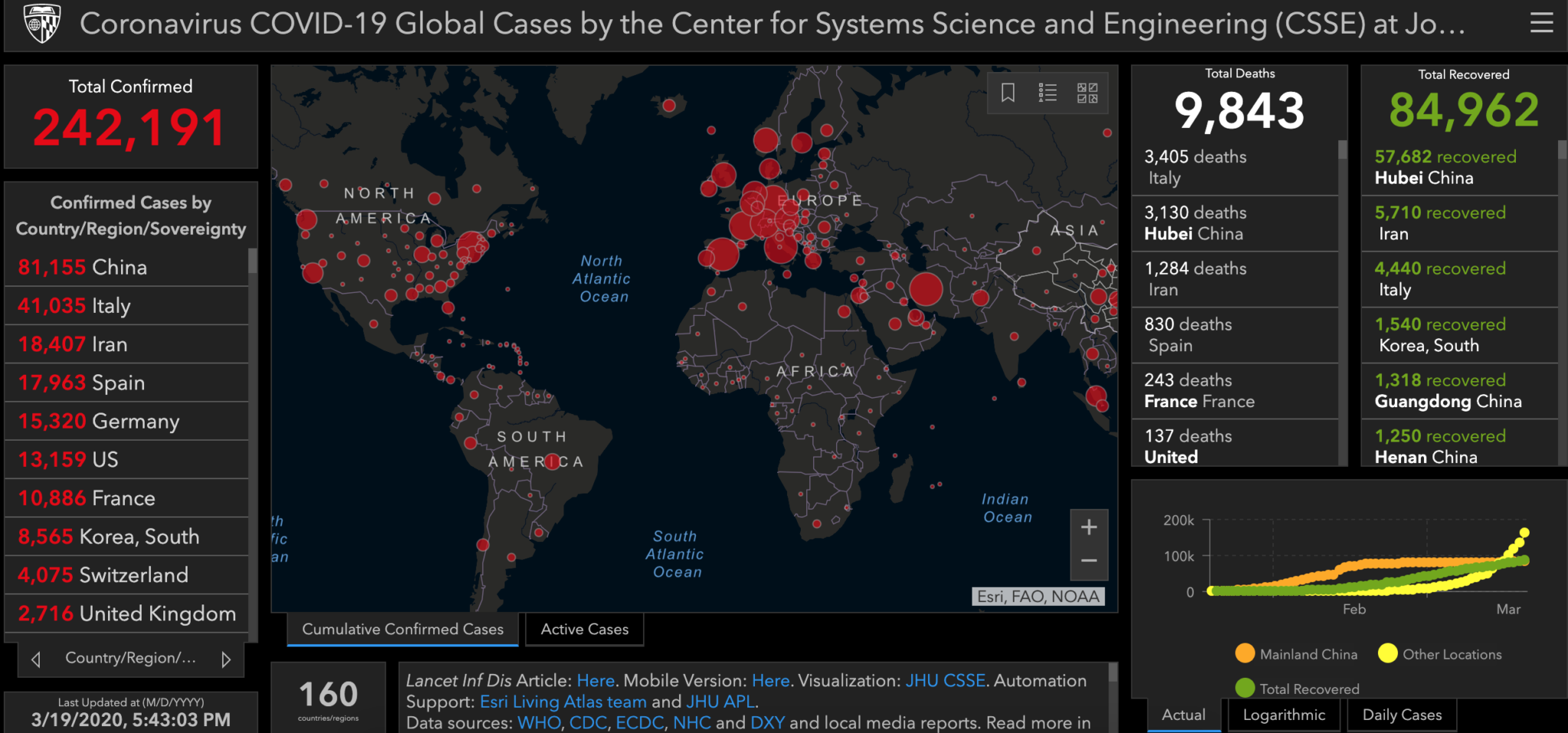

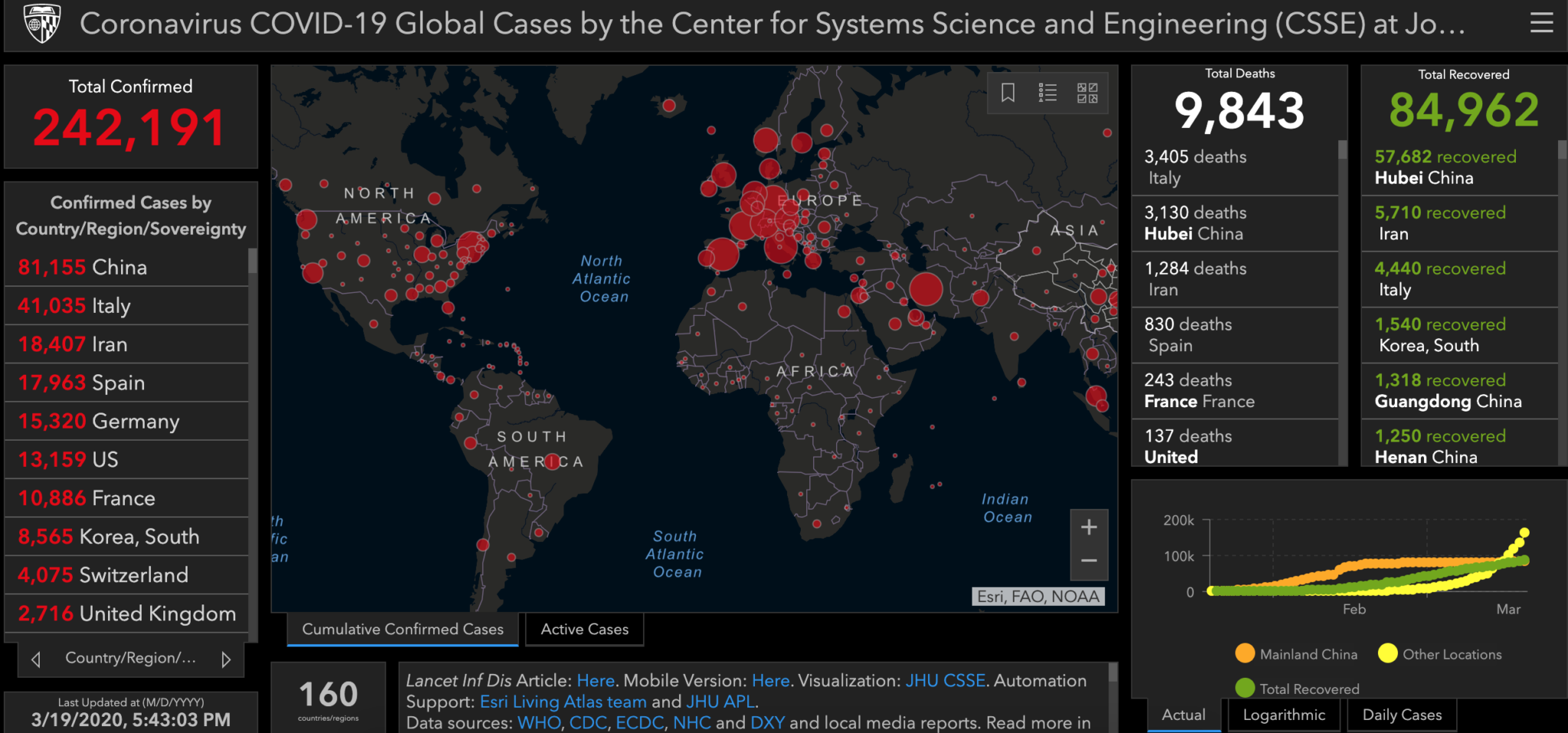

However, what the President has not abandoned is his penchant for injecting racism into every possible issue, including apparently, into the pandemic that is now affecting most of the world, having caused more than 200,000 cases and close 9,000 deaths worldwide, and as of Thursday evening, more than 13,000 cases and 100 fatalities in the United States.

Via Johns Hopkins, March 19, 2020, 5:43 p.m. ET

Instead of denying a problem exists, Trump has now shifted to calling COVID “the Chinese virus.” Trump has defended his use of the term “Chinese virus” by comparing it to pandemics with “place names,” like the “Spanish flu.” Putting aside that the “Spanish flu” originated in the United States, the larger problems is that by employing such language, Trump and his nativist advisers are exploiting a health crisis for xenophobic ends.

At a Thursday press conference, a Trump-friendly reporter gave him an opportunity to address his critics and claim that anyone who calls out the President about his words are working with the Chinese government.

An @OANN reporter asks Trump “Major left-wing news media have teamed up with Chinese communist narratives… is it alarming that major media players are consistently siding with foreign state propaganda, islamic radicals and latin gangs and cartels?”

What pic.twitter.com/uqWkhUPvgc

— Andrew Solender (@AndrewSolender) March 19, 2020

It only revealed his racism even more.

Chinese and Chinese-American people in the United States will recognize that this is not the first time they’ve been targeted this way. The Chinese Exclusion Act of the late 19th century restricted Chinese immigration to the United States in part to maintain the nation’s imagined “racial purity” and in part to shield domestic workers from foreign competition, but also in part because of accompanying social fears regarding Chinese people’s alleged propensity for catching and spreading disease. Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans were regularly accused of bringing to American shores “beastliness,” “venereal disease,” and even “leprosy.”

In Congressional debates leading up to the 1924 Immigration and Nationality Act, in which the United States expanded restrictionist measures in immigration law, limiting migration from eastern and southern Europe and outrightly excluding Asian migration, some legislators argued that stopping the flow of migration from these parts of the world was necessary because aside from “a remarkably large proportion of them [standing] low in the scale of native intelligence,” immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and all of Asia had an increased “susceptibility to disease.”

Even when immigrants were essential to the national interest, suspicion of them and fears that they carried disease abounded. When Mexicans were contracted as seasonal workers during the bracero program begun in response to World War II-era labor shortages, workers were required to go through invasive full-body inspections, to be sprayed with pesticides, and to have their health constantly scrutinized (when braceros got sick, they were often deported rather than treated). And when, amid a massive economic recession in the 1950s, Americans began to look for someone to blame for the downturn, over one million Mexican citizens (and many Mexican Americans) were deported, with removals justified not only on economic grounds but based on reports of “frightening disease” rates among them.

The HIV/AIDS crisis beginning in the 1980s was much the same story, as fears about the “African disease” served to discriminate against black migrants and refugees for decades. And more recently, fears of Central American migrants spreading disease have helped to justify the government’s draconian and inhumane policies toward them, including family separation, indefinite detention in concentration camp-like conditions, and the “Remain in Mexico” rule.

The public health implications of COVID-19 are now becoming clear. But there are also social and political implications that we should be vigilant about. It is no coincidence that as Trump insists on calling this pandemic the “Chinese virus,” immigration raids have also been ramped up in some American cities, including one of the larges, Los Angeles. History shows us that during times of crisis, people seek scapegoats and governments exploit the population’s fears and anxieties for nefarious ends.

In this climate, it is essential that we reject attempts to find scapegoats instead of solutions, that we rebuff reactionaries who seek to sow division and hate rather than unity and cooperation. The stakes are too high to allow ourselves and our governments to squander our collective energies and resources on racism and xenophobia rather on compassionate and focused efforts to protect our most vulnerable in the short-term and on containing the crisis and reforming our healthcare system in the long-term.

***

Eladio Bobadilla is an assistant professor of history at the University of Kentucky. He is an expert in immigration history and policy and a member of the Scholars Strategy Network. He tweets from @e_b_bobadilla.