(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this piece was published at the Lewis Hine Fellowship blog. The author has granted Latino Rebels permission to repost a newer version of her work.

I thought I knew the precipice and how easy it is to fall off of it. I knew the history. In 1521, my hometown of Mexico City, then the Aztec-capital of Tenochtitlán, fell to the Spanish, not due to weapons of war, but weapons of biology: in this case, smallpox. That disease ultimately killed 90-95% of the native population, paving the way for a new world order defined by global domination and dispossession. Centuries later, in 1918, my Mexican great-great-grandmother died of the Spanish flu while my American great-grandfather —on his way to fight on the Western Front— threw bodies killed by the disease into the Atlantic Ocean. The Spanish flu or la influenza española, as I grew up calling it, killed 50 million people worldwide, more than World War I itself.

Knowing that history helped inspire me during the years I spent covering armed violence and forced displacement in Latin America as a journalist, years that made me well-acquainted with sudden upheaval and premature death. And yet, that experience and the awareness of my ancestors’ history, did not prepare me for the devastation unleashed by the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City.

In early March, when it was becoming increasingly clear that the coronavirus was beginning its silent, but soon to be crushing, assault on New York City, I continued to live my life as I always had. I made plans, even as I saw events getting canceled. I rode the subway, even as I saw it getting emptier by the day. I attempted to volunteer, even as all the senior citizens I work with stayed home. I was in denial.

Perhaps I was in denial because I did not wish to see our pandemic coming. Instead, I was deeply immersed in a year-long documentary project in the woodshops and boiler rooms of New York City. As a Lewis Hine Documentary Fellow, I followed Brooklyn Workforce Innovations (BWI), a work training nonprofit that offers instruction in fields like film production, woodworking, and sanitation to low-income New Yorkers.

Ángel Pérez

At Brooklyn Woods, BWI’s woodworking program, I met Ángel Pérez, a foreman for the program’s social venture. Ángel makes vanities and cabinets for local housing developments while training recent woodworking graduates to do the same. Almost immediately, Ángel and I bonded over our mutual Latin American heritage and shared Brooklyn neighborhood. He was always making me laugh and showing me his latest creations. Every day he walked into the woodshop with a huge smile and a tape measure at his side, ready for whatever the day asked of him.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

After a few months of getting to know him, he graciously began letting me photograph him in the woodshop that has been his domain for over a decade. Instantly, I was drawn to the way he clenched his teeth as he artfully sliced slabs of wood into pieces that once put together would become furniture. I was never sure if his facial expression signaled joy or struggle, or possibly both. At the end of each workday, Ángel would look at the fruits of his labor admiringly and utter, “It’s a lot of work,” perhaps not seeing that the work he was referring to wasn’t just physical, it was also emotional.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

One day, I caught a glimpse of what looked like a bullet wound on Ángel’s stomach as he was lifting a table he had just finished assembling. In that moment I began to see that, by putting furniture together, he might also be putting himself together. As the months went by, Ángel started putting words to his story: the story of a Puerto Rican New Yorker who came of age as the flight of industry hollowed out the city’s economy and its institutions.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

Born in 1966, Ángel remembered a time when empty buildings served as playgrounds and when blackouts became riots. Without government support, communities like Ángel’s used drugs as medication for despair and crime became a natural side-effect. It was the crack era.

“People were selling their bodies, their clothes,” he once described. “You were stealing from your mother, your sister, your family. People were strung out everywhere. That’s how strong that thing was. Crack didn’t care what color you were. It was a sad, sad day in America.”

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

Without guidance or a way out, Ángel, like many of his generation started selling heroin and staging burglaries to make ends meet. Guns became a vital work tool, and eventually led to him getting shot in a gun-trade gone wrong. Ángel was brought to a nearby hospital where he was promptly handcuffed to an operating table. The handcuffs attached to his blood-soaked body served as a metaphor for a country that saw young men of color like him and the young man with a gunshot wound who passed away beside him, as a threat not only in life, but also in death.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

The scars from the bullets that nearly killed Ángel were imprinted not just on his skin, but also in his mind.

“I made it and the man next to me didn’t make it,” Ángel told me as his eyes filled up with tears. “It stays in my mind. You know? Why him? It could have been vice-versa. So maybe God had a plan for me or something.”

But at the time, Ángel’s near-death experience only led him further on a path of self-destruction.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

Sent upstate to serve his prison sentence, Ángel survived incarceration by playing handball and by making drawings of other inmates. After getting out for good in the mid 2000s, he was determined to change his life. Always good with his hands and with an eye for beauty, with the support of his sister, he ended up in one of Brooklyn Woods’ classes. Recognizing his potential, Brooklyn Woods gave him a second chance as a permanent staff member where he has been ever since. And it’s a role he takes seriously.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

“My job is to beautify things,” he told me one day as he was in the woodshop showing me how to make kitchen doors. “I guess it’s my chance to make up for all the destruction that I caused in my youth.”

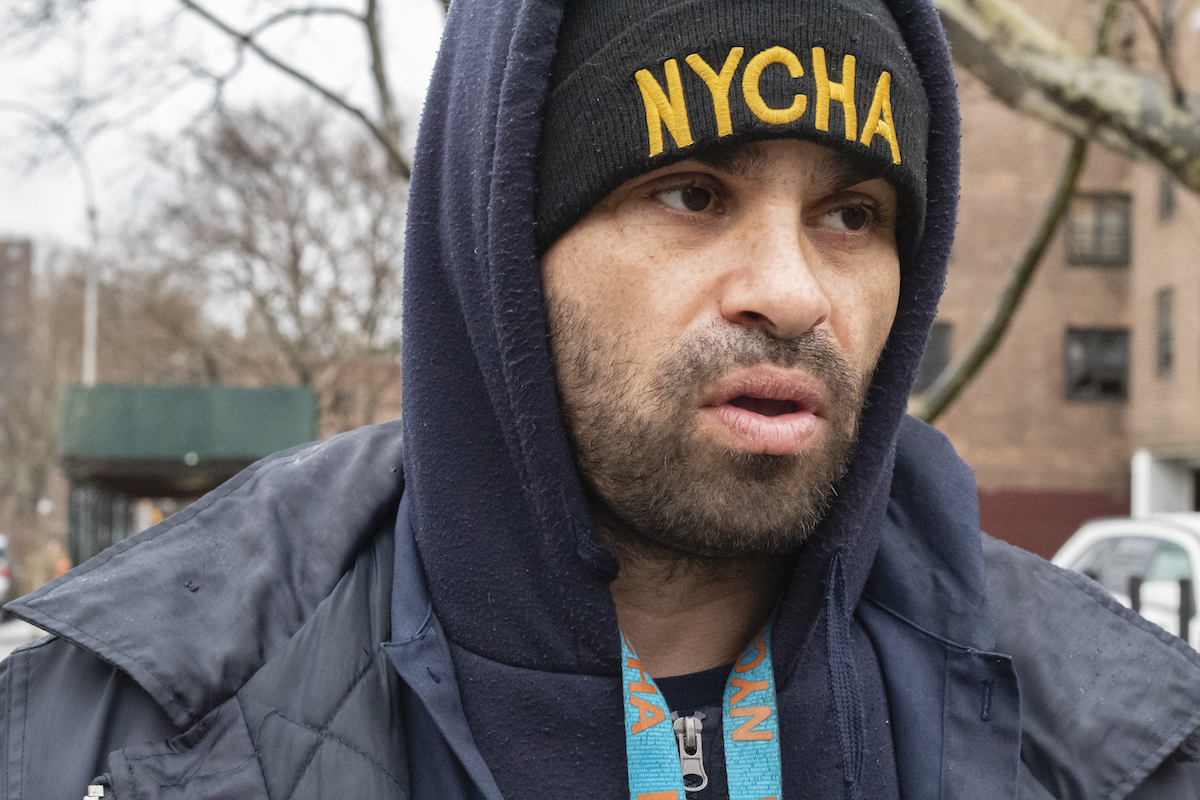

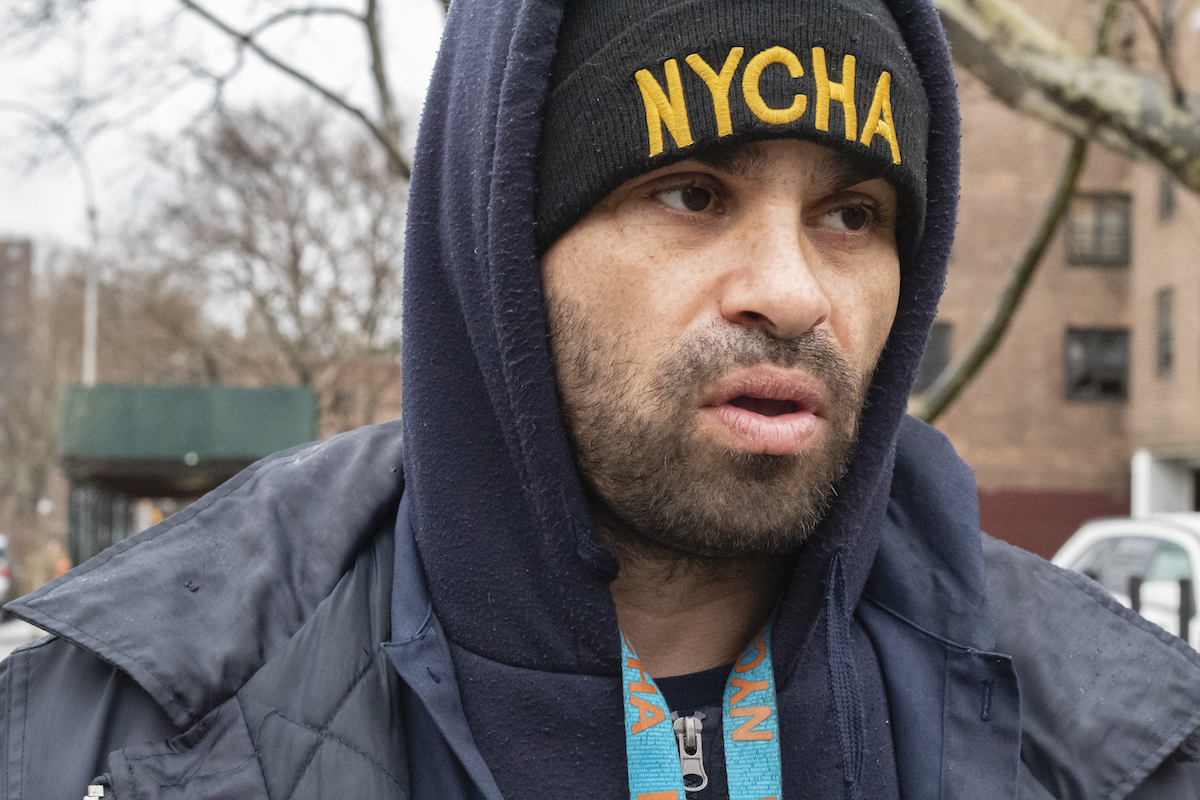

Heriks-Agosto Ramos

The philosophy of using work as a way to make up for past wrongs was echoed by another BWI alum, Heriks-Agosto Ramos. A graduate of BWI’s NYCHA Resident Training Academy, a job training and placement program for public housing residents in construction, janitorial, and maintenance fields, Heriks currently works as a heat technician in Motthaven Houses, a housing development in the South Bronx. Unlike Ángel who works in a well-lit woodshop with people coming in and out, Heriks works in a dark, underground boiler room, almost always by himself. Yet it is in that room surrounded only by van-sized boilers and the hum of gas being pumped into hundreds of apartments above that Heriks feels most at peace. After spending most of his life living under a microscope, he enjoys the quiet, the anonymity. But he does not want to be invisible.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

“I’m an ex-crack king pin,” he shared minutes after we met. We were walking down to the break room where he takes calls from residents needing hot water and where he can keep an eye on the potentially deadly machines that make that hot water possible. “I can tell you what the 80s were, the 90s, and the 2000s. I was locked up practically my whole life. Robberies, drugs, gun charges, you name it.”

His words were a stark contrast with the yellow NYCHA insignia featured prominently on the hat above his brow. Heriks is now an employee of a government that had once incarcerated him.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

When describing his journey to NYCHA, he said, “I’ve spent all my life trying to live the American Dream, but circumstances didn’t allow me to. I can say I was a victim of those circumstances and a victim to my own devices.”

Like Ángel, Heriks is also Puerto Rican. Born in 1977, he grew up in the Little Italy neighborhood of the Bronx where he was raised by his grandparents. His parents were heroin addicts who later succumbed to the HIV epidemic. Those circumstances laid the foundations for his first arrest at age eleven for stealing. Rather than receive the support he so desperately needed, he was punished, and he served his first stint in juvenile detention. It was his first sentence in what would amount to two decades spent within the confines of the criminal justice system. Two of those years were spent in solitary confinement, and all of them were spent in the shadow of a larger epidemic, the crack epidemic.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

“About 1990, 91, New York was crazy,” he said when describing his early years. “Everybody was doing crack. Everybody was selling it. It was a very violent game. People looked like zombies. Now, when I reminisce with my friends about the crack era, we call it the crack wars. It was a war out here.”

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

“Work is my sanctuary,” he says when describing the program’s impact on his life. “It’s therapeutic. I don’t have to look over my shoulder anymore. It’s a hustle, but a legit hustle. I look at life different since I started working.”

Part of that change in perspective is also due to having someone to work for. Shortly before his release from federal prison in 2008, Heriks lost his biological son in a car crash. But life gave him a second chance by allowing him to be a father to his stepson. Heriks’ stepson suffers from a life-threatening kidney condition, but rather than devastate him, it motivates him.

“I like money” he confesses. “I’ve always been addicted to money. But when I found out that my stepson had kidney problems, my whole life changed. I get paid decent money, but that’s not what I come to work for. I come to work for the medical benefits because that’s what keeps my son afloat.”

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

In a somewhat poetic culmination of events, Heriks has become a caretaker in a world that has never taken care of him.

“I guard my life with care now,” he told me as he was pointing out how he makes sure the boilers are running the way they are supposed to. “I have more to lose than anybody. I have a career and I’m a convicted felon. Not once, not twice, but three times. If I get caught doing something illegal; throw away the key.”

On the occasions I came to visit him while on the job, Heriks never took his NYCHA hat off–even as we were both sweating from the heat exerted by the boilers. It was as if in an unconscious way, he was saying, I belong here and what I have now, cannot be stripped away from me.

COVID-19

On March 13 —one week after I saw Heriks for the last time— I fled New York City to quarantine from the invisible threat that was upending the lives of billions of people across the globe. That day was also the last day I saw Ángel. One of the last photographs I made was of him, not at work, but at play. He is eating Chinese food at a graduation party for Brooklyn Woods’ last cohort before the lockdown. He looks happy and carefree. He looks excited for the new class of woodworkers, whose future seemed so bright.

By the next week, we started to hear about mass lay-offs and furloughs, as businesses struggled to adjust to the lockdown and social distancing measures that were implemented to contain the spread of the coronavirus. It became clear that the young men and women I saw graduate, had graduated not only into a health crisis, but also into a joblessness crisis. Ángel had no immunity. Because his job could not be done remotely, he was furloughed, but paid because of an excess in paid time off. Ángel had not taken a vacation in years. But paid idleness wasn’t easy either. It was too akin to a condition he had long wanted to forget—imprisonment.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

Heriks, on the other hand, became an essential worker, as people still need heat and hot water in a pandemic. But with each passing day, he was hearing about yet another resident or colleague that had gotten infected. His biggest fear was, and remains, infecting his young son who is already fighting his own battle. Work is no longer the sanctuary it used to be; it’s a risk. The virus is especially a risk for essential workers and the formerly incarcerated, but the virus and the systems that make it so deadly threaten us all.

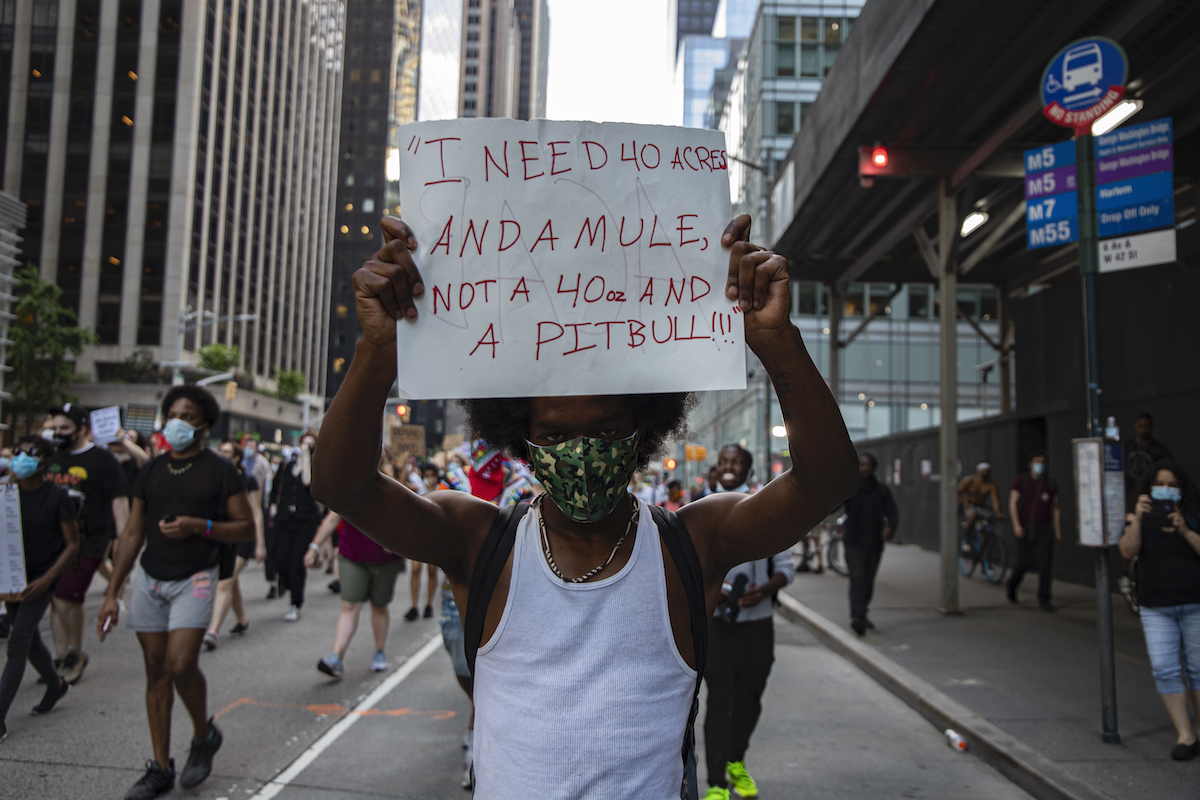

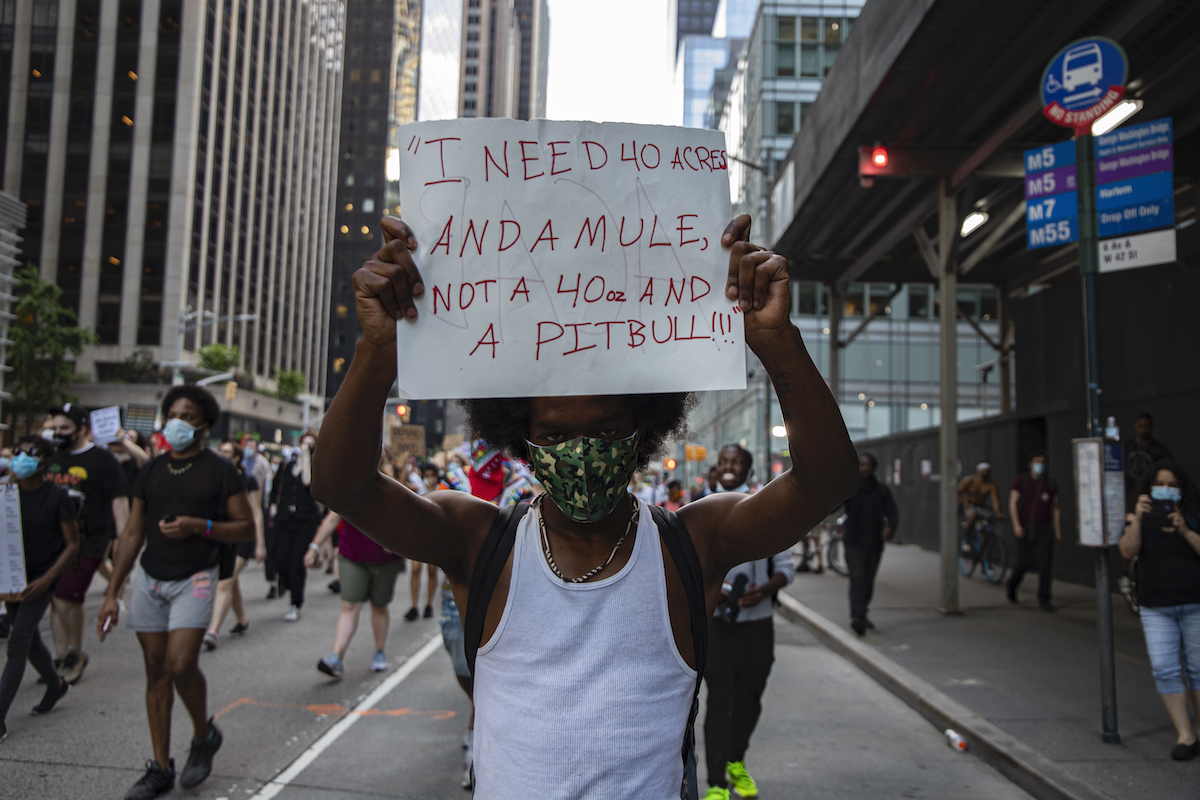

#BlackLivesMatter Protests

I came back to New York City at the beginning of June to find a city leveled by a pandemic and enraged by the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis Police Department. Tens of thousands of New Yorkers were taking to the streets not only to protest the larger all-American tradition of police brutality against Black and brown communities but also to protest this country’s stubborn resistance to atone for centuries of discrimination and violence towards those same communities whose legacy is causing them to die of COVID-19 at disproportionate rates. History was unfolding on the streets of New York City, and Heriks could not be kept away.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

After a lifetime spent on the frontlines of a series of continuous epidemics–crack, HIV, incarceration, and now, COVID-19, Heriks had seen enough. He joined the protests without fear or reservations. In watching George Floyd’s pleas for air be silenced by an indifferent police officer, he not only saw his own experiences at the hands of the law enforcement; he also saw the experiences of the residents of his housing development who in the last several months had had their pleas for air silenced by a deadly disease spread by government inaction. He had to speak. And so, he marched. He marched for his son. He marched for his community. He marched for his friends in prison who would never get the chance to march. And most importantly, he marched for himself. But the backdrop of the pandemic lingered. Soon, what had propelled him to the streets, forced him to evacuate them. His work partner caught COVID-19 and he has been working 16-hour shifts since.

Ángel on the other hand, has taken a different approach to the protests. He has stayed home. His decision to stay home is not out of a lack of sympathy, it’s out of precaution. “I try to stay away from big crowds,” he said when I asked him if he had plans to attend any of the marches. “Because of prison, I have to assume the worst in people. I can’t trust others. People like to use this new word, ‘social distancing’, but for me that word is nothing new. I’ve been doing that for over twenty years.” In speaking those words, Ángel laid bare the silencing after-effects of incarceration, and in doing so, underscored the urgency of the young people who have taken to the streets demanding a future where living in fear is not normal. In another way, Ángel was implicitly trying to compare a crisis whose magnitude we have yet to fully grasp to one he knew well, prison.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

When Ángel and I spoke about social distancing, it was late June. He had recently returned to work and was standing in the woodshop, alone. I had never seen it so quiet and empty.

“I’ve always wanted this place to be quiet and left alone,” he said when we walked into a room full of unused saws. “But now that I have that, all I want is for there to be a class again.”

There was a new woodworking class, but due to social distancing measures, much of the class was being taught remotely. City budget cuts along with a decline in construction also meant that work was slow. Not having anything to do or anyone to share it with was hard on Ángel. He was fidgety. He kept on pacing around trying to find something to keep him busy. Something to clean. Something to design. Something to beautify.

Even as the death toll and infection rate have declined significantly in New York City, the possibility of a second wave persists. We put on masks to leave the house. We try to stay six feet apart. We make meetings virtual. We do curb-side pickup. We take our temperature. We always carry hand sanitizer. And we act as if everyone has the virus and as if we have the virus. These rituals are not unlike the risk-minimization rituals performed by the veterans of drug wars I have worked with in Latin America and in the United States—including Ángel and Heriks. People taught to show anger rather than sorrow. To join powerful street crews as protection. To see but not speak. To walk around with weapons. To value money more than life. And most harmfully, to assume the worst in people–even when human connection is the very thing that can help us heal.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

While different in their scope and in the harm they protect us from these risk-minimization rituals are at their core, rituals of distrust, but not without purpose. They help us survive and at times, like they are now, they are necessary. But if the lives of Heriks and Ángel have taught me anything, it’s that the cost of survival can be steep. Sometimes, it can even cost us, who we are. In the crisis of the moment, rituals of distrust will have to persist to save lives and with jobs as their casualty. Until people can trust that they can leave their homes without acquiring a deadly pathogen, and business can trust that they can operate without unexpected closures or sudden drops in demand, for better or worse, normalcy will not return. In a moment where anguish and precariousness are an epidemic in themselves, we should begin to ask ourselves how to cure those ailments. But we can also ask, as the protests have begged us to ponder, why in times of normalcy do we tolerate so much anguish and precariousness?

A Form of Relief

As a photographer, I have found a way to approach answering those questions in the only way I know–through my photographs. Since returning to New York I have gone out to document the protests. I have taken thousands of pictures of young people speaking on behalf of survivors of police brutality and incarceration like Ángel and Heriks who cannot be there to tell their stories. And it’s in witnessing their absence and our country’s choice to ignore their plight that I see why so little has been done to change the circumstances that led to their dehumanization. When you choose not to see a problem and silence those affected by it, it becomes easy to ignore. But if there is anything I have learned after spending nearly a year photographing individuals who survived the unimaginable, it’s that their stories can provide crucial insight into a form of relief for so much of the anguish and precariousness that afflicts our society: meaningful employment.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

As I sit looking over my photographs of Ángel and Heriks at work, in the weeks preceding the COVID-19 lockdown, I see so much joy and so much peace. I am reminded of the words of Khalil Gibran who once said, “work is love made visible.” In a country that never showed them compassion, they have found compassion towards themselves by finding a calling and having that calling nurtured: by working. Across the country millions are sitting idle whether it be in a prison cell, in a crowded apartment, in a single-family home, or on an empty street corner. But if this country is to recover from the pandemic, it must get rid of the societal preexisting conditions that made it so deadly–poverty and despair. To eradicate these preexisting conditions and to subsequently make sure that the damage from COVID-19 is not permanent, it will be necessary to give everyone access to workplaces where they feel and are treated as essential. To become whole, we must build a nation where all work has dignity, but most importantly, we must build a country where everyone, regardless of who they are —and with a meaningful consideration of existing differences in health and ability— is given a chance to contribute and to feel valued.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo)

On one of the occasions I visited Ángel during this pandemic summer, he was standing in the middle of his woodshop trying to figure out what to do next to occupy his mind. He turned to me and asked, “Do you think I’ll be okay?”. I didn’t know how to respond or if I could even make that judgement, but I replied with what I saw happening on the streets: “Yes, there is so much work to do.”