Cemetery workers in protective clothing inter three victims of the new coronavirus at the Vila Formosa cemetery in São Paulo, Brazil, Wednesday, July 15, 2020. (AP Photo/Andre Penner)

By DAVID BILLER, Associated Press

RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — The story of COVID-19 in Brazil is the story of a president who insists the pandemic is no big deal.

Jair Bolsonaro condemned the idea of coronavirus quarantine, saying shutdowns would wreck the economy and punish the poor. He scoffed at the “little flu,” then trumpeted the fatalistic claim that nothing could stop 70% of Brazilians from falling ill. And he refused to take responsibility, when many did.

Asked in April about Brazil’s death toll surpassing China’s, he responded: “So what? I lament it. What do you want me to do?”

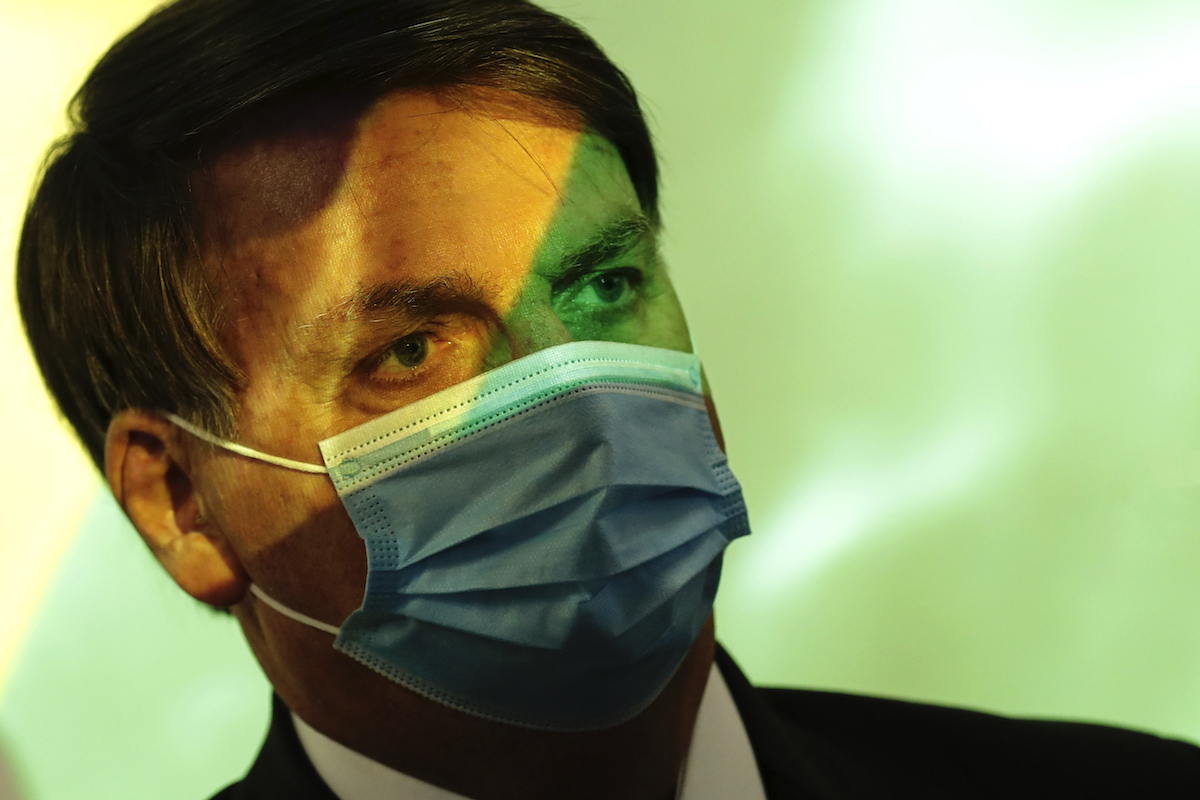

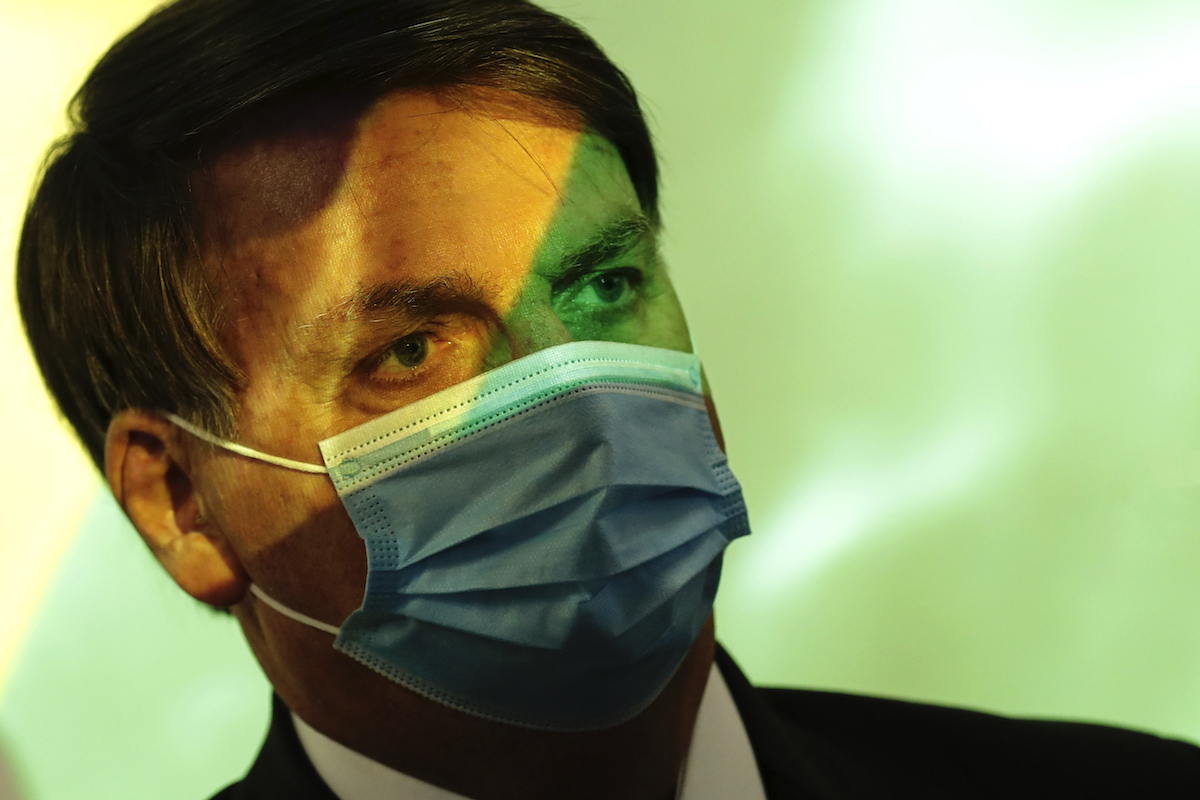

President Jair Bolsonaro wears a mask amid the COVID-19 pandemic at the start of a ceremony where the national flag is projected in Brasilia, Brazil, Wednesday, August 5, 2020. (AP Photo/Eraldo Peres)

Those words crystallized how many came to view Brazil’s pandemic response. For Márcio Antônio Silva, a resident of Rio de Janeiro who’d recently lost his 25-year-old son, they were a gut punch.

“I put him in the coffin, shut it and said, ‘My son, they will take care of you.’ And two days later I hear, ‘So what?’” Silva said. “It hurt so much. That’s maybe what hurts most today.”

Bolsonaro’s key actions were pragmatic and economic, albeit delayed and partially spurred by Congress. He enacted measures to prevent worse layoffs and doled out emergency coronavirus payments. Among the developing world’s most generous, they brought extreme poverty to its lowest level in decades and boosted his popularity.

Residents attend a ceremony on a soccer field after getting basic training from health workers on how to stay safe in their community during the COVID-19 pandemic in São Paulo, Brazil, Wednesday, May 6, 2020. (AP Photo/Andre Penner)

Bolsonaro could have inspired people to hunker down, too, but instead he encouraged them to flout local restrictions—restrictions that he himself undermined by going out and drawing crowds. And he successfully lobbied for official soccer matches to resume, just as the pandemic peaked.

Denial was widespread in the Amazon city of Manaus, even as its cemetery was digging mass graves and patients were boarding puddle jumpers to go to hospitals. Contagion traveled upriver to Indigenous territories. In São Paulo’s towers and along Rio’s beaches, quarantine defiers echoed Bolsonaro’s dismissal of the disease.

At Copacabana, someone toppled crosses symbolizing the fallen. Silva, the grieving father, drove them back into the sand while pleading for respect.

The president fired one health minister for supporting measures hampering activity. A second quit because Bolsonaro promoted chloroquine—a drug closely related to the anti-malarial medication championed by U.S. President Donald Trump that Bolsonaro himself took when he contracted COVID-19. His third health minister was an army general with no pre-pandemic health experience.

The health ministry said in a statement that it has distributed tests for more than 10 million people. That’s not close to enough, said Pedro Hallal, an epidemiologist who coordinates the Federal University of Pelotas’ testing program, by far Brazil’s most comprehensive. He says Brazil’s government hasn’t valued testing and the nation probably had about 40 million infections—five times the official tally.

Worse, there’s no contact tracing. Hallal said he knows that from experience: No one reached out to family members when his parents tested positive.

Brazil’s viral curve looks like few others: Rather than a crest, it shows a three-month plateau of roughly 1,000 daily deaths.

By mid-December, the country had reported 85.3 cases per 100,000 population.

Due to the government’s COVID-19 cash bonanza, the International Monetary Fund forecasts 5.8% contraction for Brazil — the best 2020 outlook of six major Latin American economies. And the rise of unemployment has been limited, up to about 15%.

The iconic Christ the Redeemer statue is lit up as if wearing a protective mask amid the new coronavirus pandemic, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on Sunday, May 3, 2020. (AP Photo/Leo Correa)

But low new jobless claims obscure fewer people seeking work, said Andre Perfeito, chief economist at Necton Investimentos. That will change as the pandemic outlay winds down and the labor force swells, revealing “real” unemployment—already approaching 25%. Layoffs also are anticipated.

Infections have rebounded after local leaders eased restrictions and pandemic fatigue set in, and are nearing the level of the July peak. Hallal expects this surge will have more infections each day, though fewer deaths.

The president’s playbook is little changed. Bolsonaro maintains there’s no time for hand-wringing, and Brazil’s economy needs to start humming.

“We’re all going to die someday. Everybody here will die,” he said in early November, as he announced measures to restart tourism. “There’s no use avoiding reality. We have to stop being a country of sissies.”