Demonstrators kneel during an April protest near Logan Square in Chicago (Photo by Mateo Zapata/@mateoxzapata)

CHICAGO — Little Village, a predominantly Mexican neighborhood on Chicago’s south side, has been at the center of one of the city’s most violent gang rivalries for decades. It’s also home to the second highest-tax generating district after the downtown district in Michigan Avenue.

La Villita, its cultural surname, also has the city’s Cook County jailhouse within its boundaries and a significantly large amount of disconnected youth who aren’t in school or employed. It’s a community physically surrounded by the intersection of the prison industrial complex, entrepreneur-driven capitalism, marginalized youth and recurring gang violence.

You can’t walk three blocks without spotting a street vendor selling elotes or fresh fruit diced in a cup peppered with chile and a few lime squeezes. Corner stores in La Villita have everything from t-shirts, two-percent milk, and school supplies to cell phones with prepaid minutes.

It’s just also one of those places you have to watch your back and not stare at people passing by in cars for too long. I graduated from an alternative high school in Little Village. Most of the students were gang members, teen parents or kids labeled “at-risk” that administrators kicked out of school. One day, for instance, I was standing on the sidewalk after school with others, when someone randomly shot at us four times from across the street. It’s pretty regular to get shot at from time to time growing up on our side of the city.

Two girls in traditional clothing during an April demonstration for Adam Toledo in Chicago’s Little Village. (Photo by Mateo Zapata/@mateoxzapata)

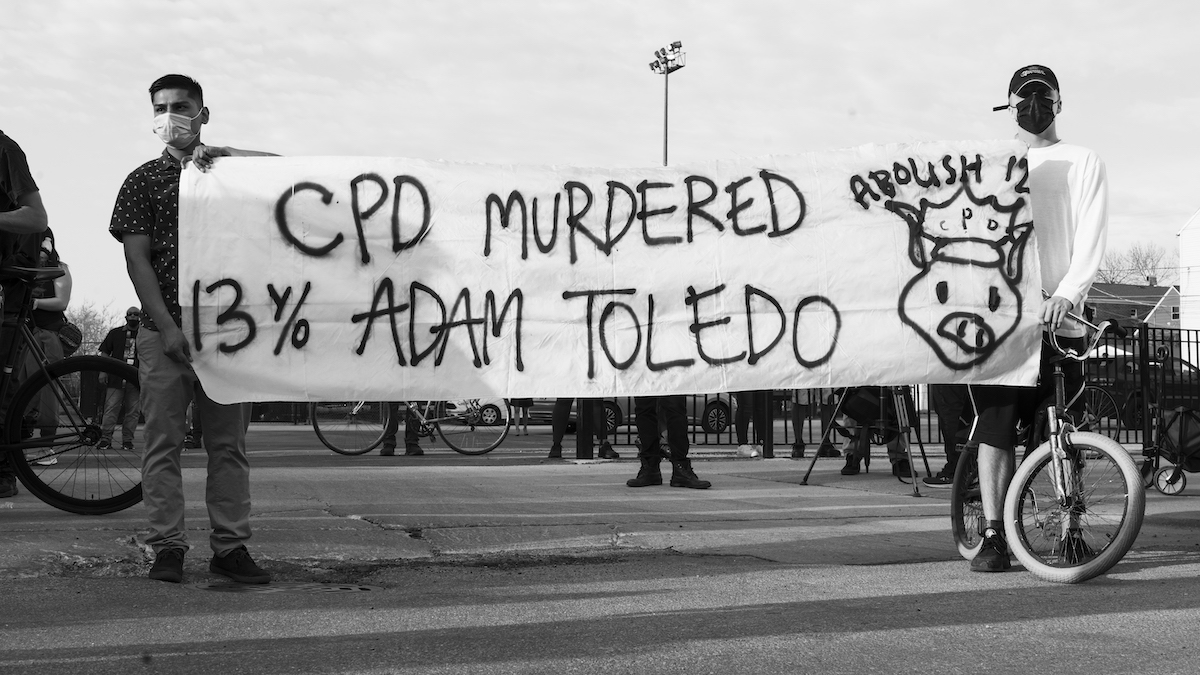

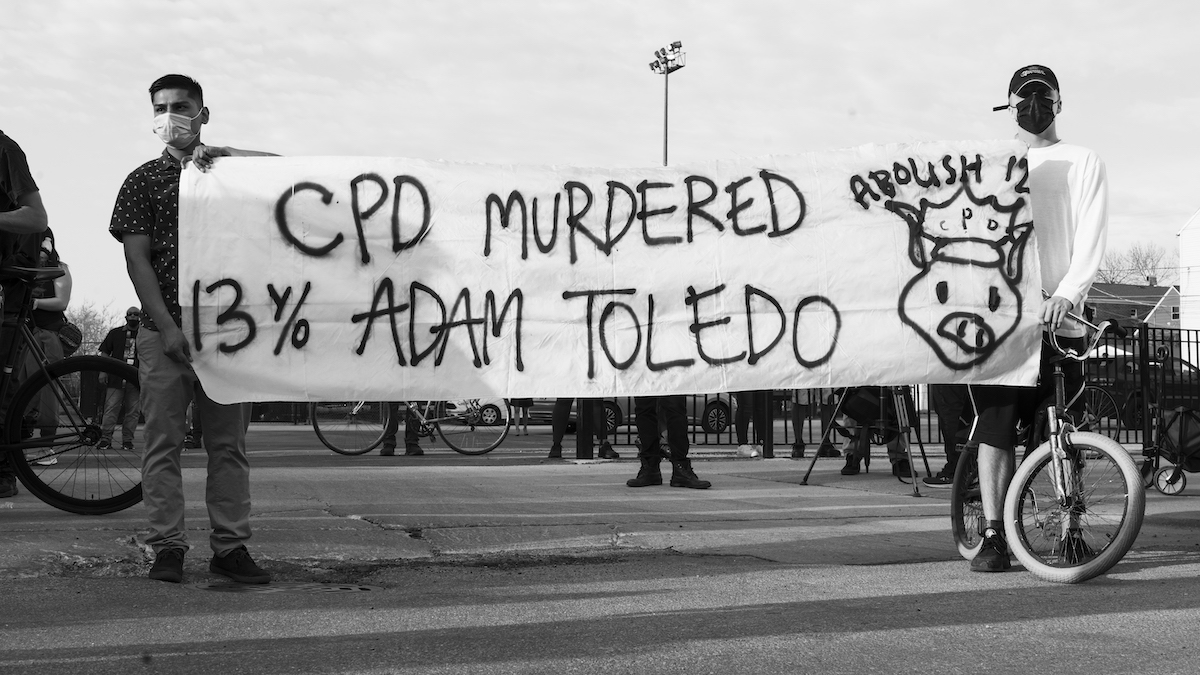

Four weeks ago, Adam Toledo, a 13-year-old child, was out late Monday night, running through an alley behind a church and high school. Adam snuck out of his room and was hanging out with Ruben Roman, a 21-year-old gang member who was armed with a Ruger 9mm pistol.

Ruben and Adam started getting chased by police, and Ruben gave Adam his pistol. Adam ran, tossed the gun behind a fence while officer Eric Stillman yelled, “Show me your fucking hands” twice. Adam complied, raised both of his hands in the air and was unarmed when he was murdered.

The police officer reported Adam as a John Doe between the ages of 18 and 24 years old. He also didn’t designate Adam’s skin complexion, hair or eye color on his incident report. Officer Stillman did fill out all of his own racial demographics in the report.

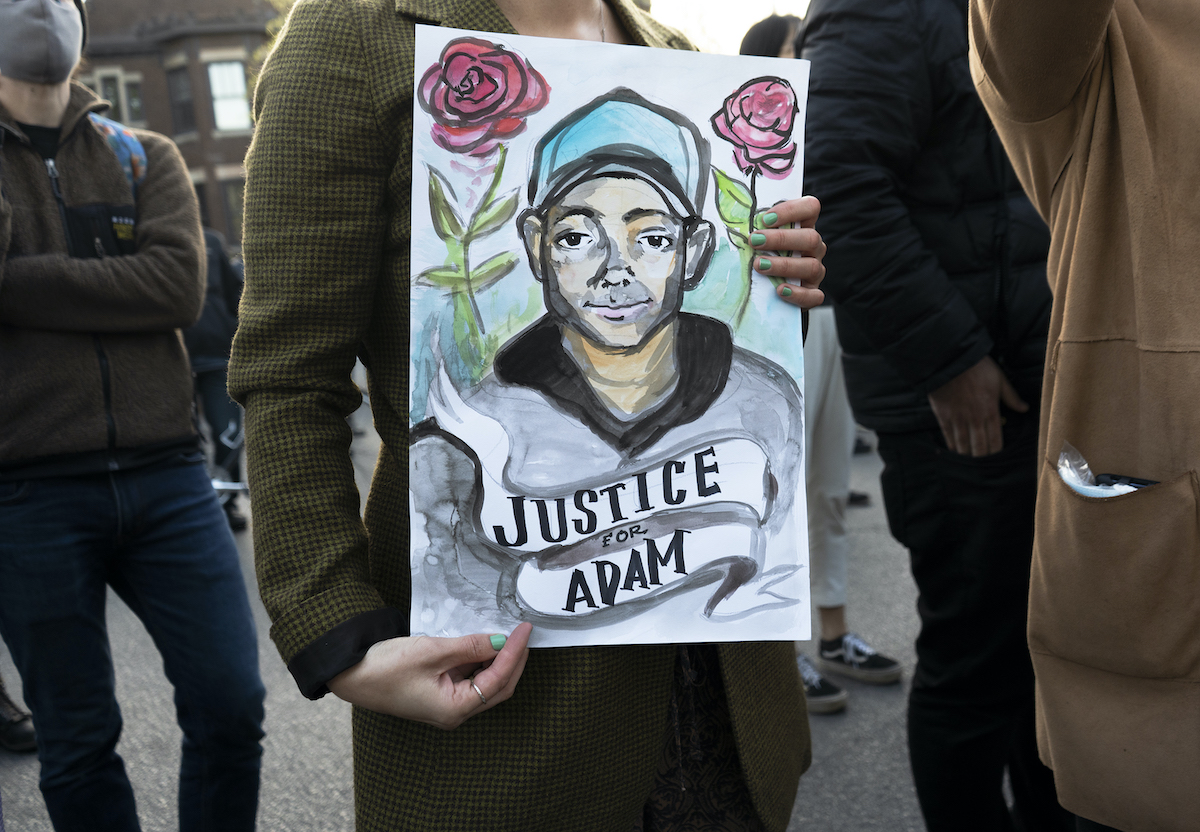

A demonstrator holds a “Justice for Adam” sign at an April protest in Chicago’s Logan Square. (Photo by Mateo Zapata/@mateoxzapata)

In addition, Chicago police waited over 48 hours to tell Adam’s family that his life was taken by police. Before the April 15 release of Stillman’s bodycam footage, James Murphy, the prosecutor at Roman’s bond court hearing, lied to the judge and stated Adam was armed when he was murdered by police. Murphy was eventually placed on leave for three days after officer Stillman took Adam’s life.

Adam’s death is not an outlier. Just days after Adam died, Anthony Alvarez was shot and killed by police during a foot pursuit on the city’s north side. Last year, Marc Nevarez was also killed during a foot pursuit in Little Village, while running from police in broad daylight. The Chicago Police Department is developing a tendency of killing Black and Brown youth during foot pursuits throughout the city and utilizing suspected gang affiliations to justify their use of lethal force.

Adam Toledo was labeled a special education student by the Chicago public school system when he was around seven years old. Adam didn’t have any severe learning disabilities but was separated from the general school population at a young age. He had “God-given talent to draw,” according to one of his former teachers. Adam didn’t grow up in Little Village. He had only been living there for a year throughout the pandemic.

We need to carefully identify the impact the last year has had on inner-city youth, and how necessary it is for our families, schools and communities to provide a space for our children that can allow them to process their traumas, challenges and overall experiences this past year.

When community residents yell, “Defund the police” throughout the streets at protests, they’re demanding for their communities to have resources such as violence prevention initiatives, afterschool programming, mental health services and creative arts instructional opportunities.

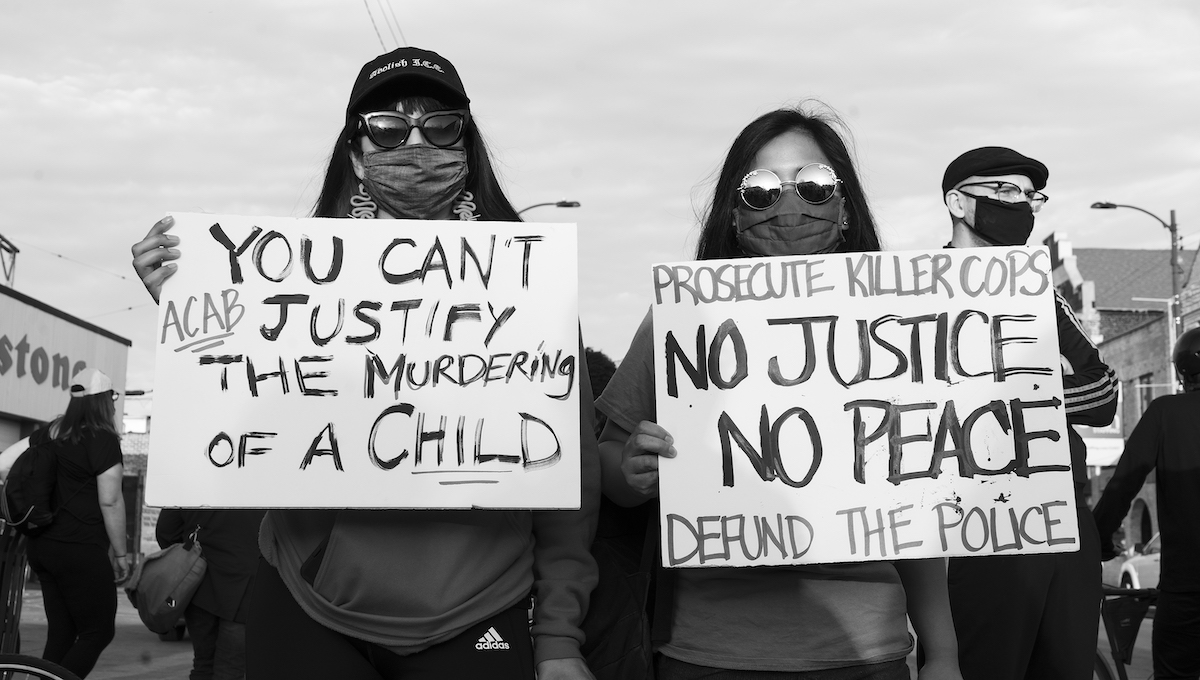

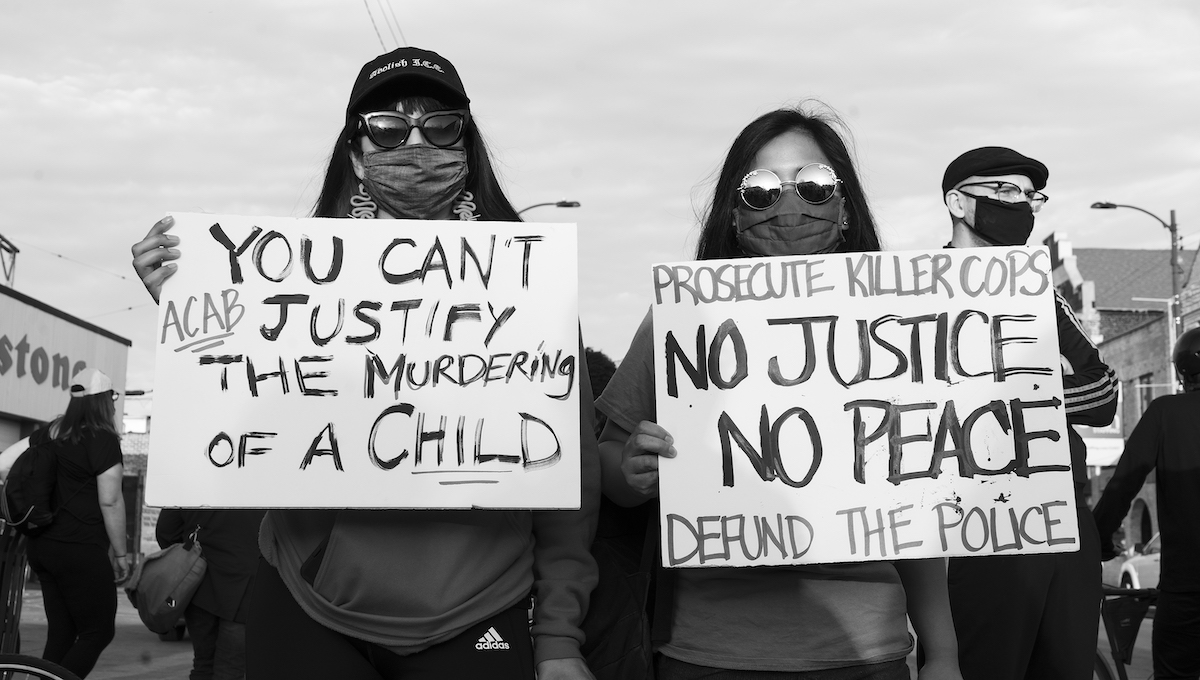

Demonstrators hold signs during an April protest in Chicago’s Little Village. (Photo by Mateo Zapata/@mateoxzapata)

Yet, such demands are still not being met. Mayor Lori Lightfoot allocated more than half of the city’s COVID-19 federal relief funding to the Chicago Police Department, totaling $281 million. Black and Brown communities in Chicago had the highest COVID-19 contraction and death rates along with initial unequal access to vaccines. Funding our communities needs to be prioritized instead of continuously increasing CPD’s budget.

Police are not preventing crime in Chicago—they’re perpetuating violence.

Demonstrators hold signs during an April protest in Chicago’s Little Village. (Photo by Mateo Zapata/@mateoxzapata)

I was 15 years old the first time a gang member handed me a pistol. We are all capable of transforming our lives and outgrowing the adolescent need to prove your manhood by participating in criminal activity. Chicago’s children deserve to exist in peace and have the opportunity to grow up safely instead of being treated as lost causes.

***

Mateo Zapata is a Chicago-based photojournalist. You can following his latest works on his Instagram: @mateoxzapata.

[…] who has been chronicling the community response to Adam’s death. Recently, Mateo wrote the following piece for Latino Rebels: “Reflections From Chicago, 4 Weeks After the Death of Adam […]