In this Tuesday, November 5, 2019, file photo, Lizbeth poses for a portrait in a relative’s home in Tijuana, Mexico. Lizbeth, a Salvadoran woman seeking asylum in the United States, never thought she would be returned to Mexico to wait for the outcome of her case, after suffering multiple assaults and being kidnapped into prostitution on her journey through Mexico. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull, File)

By ELLIOT SPAGAT, Associated Press

SAN DIEGO (AP) — In March of 2020, Estela Lazo appeared before immigration Judge Lee O’Connor with her two children, her muscles tensed and a lump in her throat. Would they receive asylum?

O’Connor’s answer: No—he wasn’t even ready to consider the question.

But he issued a ruling that seemed promising: It was illegal to force the Honduran family to wait in Mexico, under then-President Donald Trump’s cornerstone policy to deter asylum-seekers. O’Connor said he was dismissing their case due to government missteps and scheduled another hearing in his San Diego courtroom in a month.

Paradoxically and typically, the family was sent back to Mexico to await its next day in court.

But when Lazo, her 10-year-old son and 6-year-old daughter appeared at a Tijuana border crossing for the follow-up hearing, U.S. authorities denied them entry because their case had been closed.

Lazo’s inability to have her claim even considered on its merits is one of many anomalies of the policy known as “Remain in Mexico,” an effort so unusual that it often ran afoul of fundamental principles of justice—such as the right to a day in court.

As President Joe Biden undoes Trump immigration policies that he considers inhumane, he faces a major question: How far should he go to right his predecessor’s perceived wrongs?

Biden halted “Remain in Mexico” his first day in office and soon announced that an estimated 26,000 asylum-seekers with active cases could wait in the United States, a process that could take several years in backlogged courts. More than 10,000 have been admitted to the U.S. so far.

But that leaves out more than 30,000 asylum-seekers whose claims were denied or dismissed under the policy, known officially as “Migrant Protection Protocols.” Advocates are pressing for them to get another chance.

Many asylum-seekers whose claims were denied for failure to appear in court say they were kidnapped in Mexico. Others were too sick or afraid to travel to a border crossing in a dangerous city with appointments as early as 4:30 a.m. Human Rights First, an advocacy group, tallied more than 1,500 publicly reported attacks against people subject to the policy.

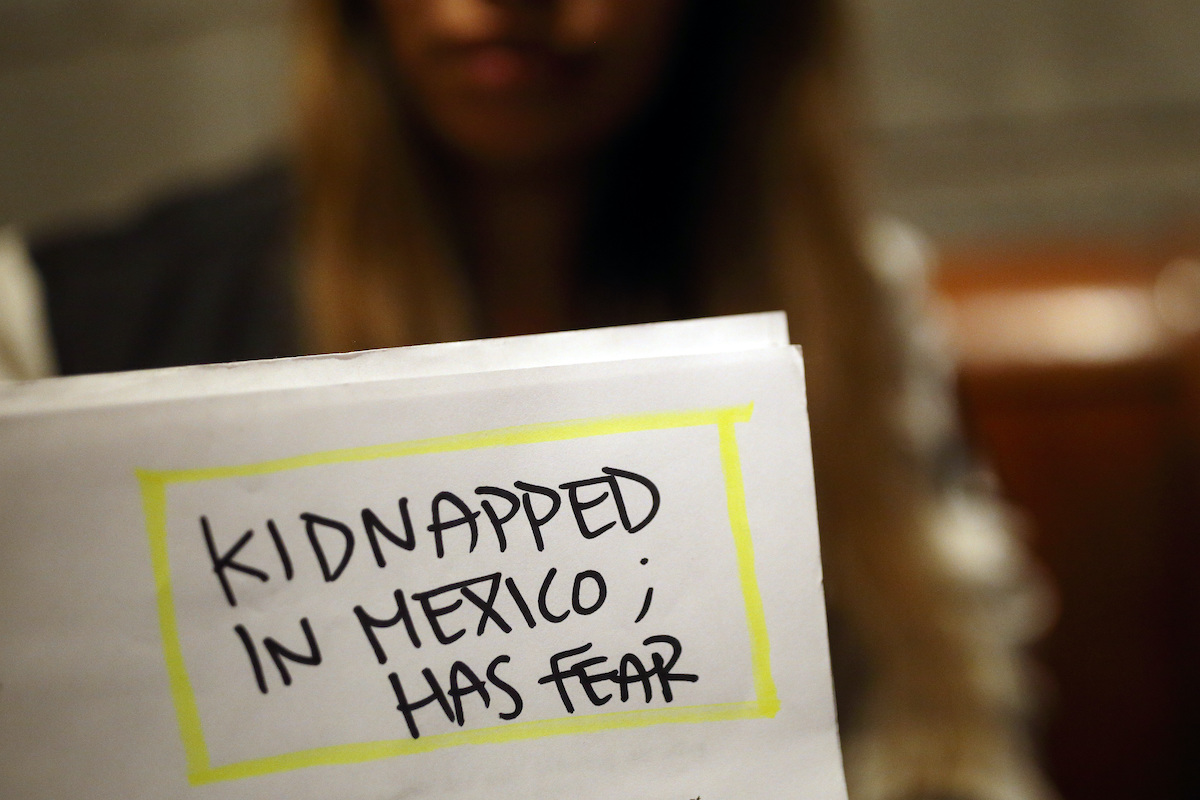

Lizbeth holds paperwork from her asylum case in a relative’s home, Tuesday, November 95, 2019, in Tijuana, Mexico. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull, File)

Then there are about 6,700 asylum-seekers like Lazo whose cases were dismissed, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. It was usually after judges found the government erred applying the policy. Many were returned to Mexico indefinitely, some after U.S. authorities filled out forms with fake court dates to make sure Mexico took them back.

In San Diego more than 5,600 cases were dismissed. When a Homeland Security attorney challenged Immigration Judge Lee O’Connor at a hearing in October 2019, he thundered that he took an oath to uphold U.S. laws, “not to acquiesce when they are flagrantly violated.”

For Lizeth —who spoke to The Associated Press on condition that her full name not be published due to safety concerns— an O’Connor ruling led to a Kafkaesque nightmare.

Lizeth said she fled Santa Ana, El Salvador, in January 2019, on the run from a police officer who demanded sexual acts. Then 31, she never said goodbye to her five children —ages 5 to 12— fearing the officer would discover where they lived.

Her freedom was short-lived. She said she was kidnapped near Mexico’s border with Guatemala, and her captors drove her in a minivan to Ciudad Juárez, across the border from El Paso, and forced her into prostitution. She escaped four months later and entered the U.S. illegally at San Diego.

When O’Connor dropped Lizeth’s case in October 2019, saying she was illegally returned to Mexico, U.S. Customs and Border Protection gave her slip of paper to appear for court on December 16, even though no hearing was scheduled. Asked about the fake court dates that she and other asylum-seekers received, CBP said at the time that they were intended as check-ins for updates on the status of their cases, but the notice didn’t say that and updates are done over the phone or online.

The Justice Department’s Executive Office for Immigration Review, which oversees immigration courts, said it does not comment on judges’ rulings.

It is unclear how often CBP issued “tear sheets” with fake court dates to get asylum-seekers with dismissed cases back to Mexico, but anecdotal evidence suggests it was common for some time. San Diego attorney Bashir Ghazialam has about a dozen clients who got fake court dates in late 2019 after their cases were dismissed and knows about three dozen more from other lawyers.

Estela Lazo stands for a portrait with her two children, late Tuesday, February 23, 2021, in Tijuana, Mexico. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull)

Carlos González Gutiérrez, Mexico’s consul general in San Diego, said he learned about the fake court dates from news reports and non-governmental organizations in late 2019, leading Mexican immigration authorities to more closely examine documents of asylum-seekers being returned to wait. The practice appears to have lasted about three months.

The judges’ core reason for dismissing cases was technical: Only “arriving aliens” should be eligible for “Remain in Mexico,” or anyone who appears at an official port of entry like a land crossing. People crossing the border illegally —who made up about 90% of those subject to the policy— are not “arriving aliens” as defined by law.

Faced with having their cases dismissed, the Border Patrol regularly left blank a place in charging documents that asks how asylum-seekers entered the country. When they reported for their first court dates, U.S. authorities amended their complaints to say —falsely— that they first sought to gain entry at an official crossing, making them “arriving aliens.”

The administration has yet to say if asylum-seekers whose cases were denied or dismissed under “Remain in Mexico” will have another shot. When asked, aides have emphasized Biden’s promise of a “humane” asylum system to be unveiled soon.