Photos courtesy of Penguin Random House

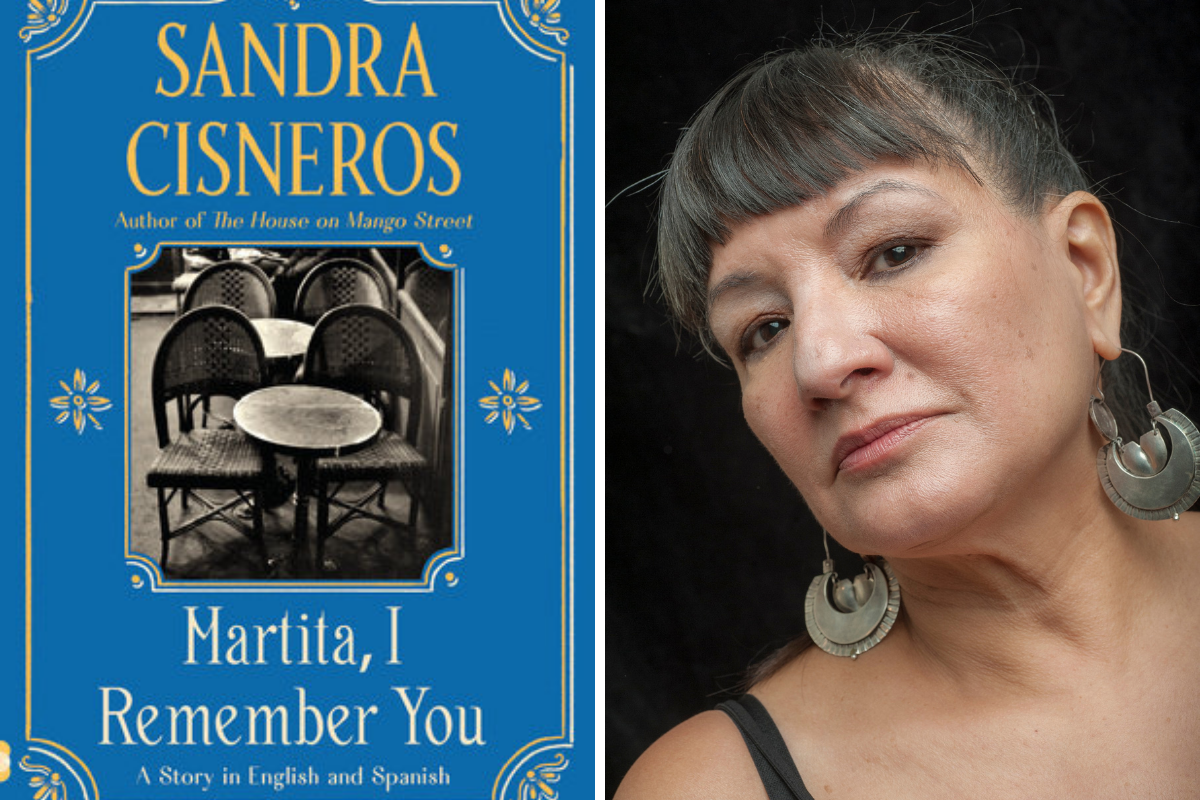

Sometimes you receive emails that are most certainly a scam or spam, while other times you receive one with an unexpected opportunity. Such is life in our modern times, and so, when out of nowhere, I receive an email full of unexpected opportunities —the chance to interview Sandra Cisneros about her newest book, Martita, I Remember You— I just had to say yes.

For many Chicano and Latinx writers of my generation, Cisneros opened the publishing world to our stories through her works of fiction —The House on Mango Street, Caramelo, Women Hollering Creek— along with her essays and collections of poetry.

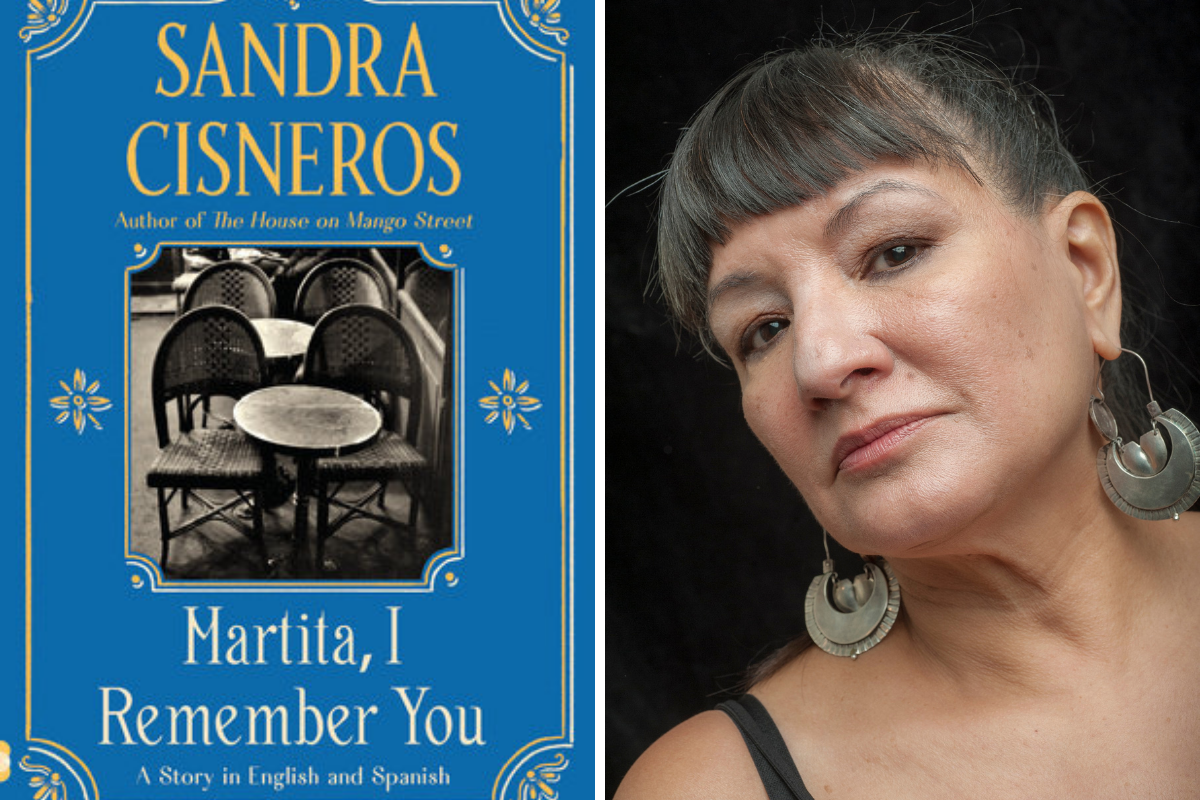

Martita, I Remember You, a novella about Corina, told through a series of letters between her and her friends recounting their youthful travels and missed opportunities, is an expansion of the Latinx narratives that she first shared with the world in the mid-1980s.

As with most things in a COVID-19 era, we meet over Zoom —me in Denver, Sandra from her home in Mexico— and over the course of almost an hour, we discuss her book, new projects in the works, and finding alternate reality versions of yourself in your work.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Sandra Cisneros: You know, I’m excited because yesterday I finished my book of poetry and in the next couple of weeks, this book is coming out. So, it’s a very productive time for me. I have a lot of projects I’m working on right now, besides introducing my new child.

Manuel Aragon: Your new child, Martita I Remember You is out. Tell us about the book.

Sandra Cisneros: Okay. This is a short story that I began when I was writing Women Hollering Creek. I began it in the 90s hoping to make that part of the collection, but it really didn’t fit in cause the stories in Women Hollering are about the Southwest or about Mexico. And this one just kind of was this weird duck. It didn’t belong.

At the end of 2015 in Mexico, I’m always working on lots of things, but trying to see what sparks, what, what comes to life. I took this out of storage, and I said, oh, that’s a pretty good story. It’s very dense. But it didn’t want to be longer. And it, it is what it is, a novella as some are calling it. I finished it during the pandemic last spring.

Manuel Aragon: It’s written as an epistolary novella, right? Its letters back and forth immediately transported me into the world of Corina, Martita, and Paola. Why did you choose that format of kind of the found letters that trigger the remembrance of the past?

Sandra Cisneros: When I began the piece, I didn’t realize that that first part was going to be like a letter, a letter that she never sends. I didn’t realize until I got to the end and said, oh, the whole story is a letter, isn’t it? You know how sometimes you write letters, or you say things to people, “Oh, I should’ve said this.”

You never mailed that letter. It’s all in your head. So, it’s kind of this interior monologue that the protagonist Corina is writing a letter that she never sends because you know, sometimes in the old days, when we wrote real letters, you know, you would wait until you had some good news. We would wait until like, you know, things aren’t going bad.

You don’t want to tell people about that. Plus, you can’t even repeat it to yourself, let alone put it on paper. And, then we lose touch with people because sometimes the bad chapters are, are very long. I think I couldn’t finish this when I was younger because I needed to, I needed to go through loss, time was necessary. You know, it was kind of like bread that needed to rise.

Manuel Aragon: Where do you blur your lines between fiction and your own reality?

Sandra Cisneros: Well, some of it is, you know, some of it is me. A lot of it, the Chicago parts and my father, but you know, not the marriages or the children or the disastrous relationships or the spontaneous abortions.

Those I gathered from other women that I’ve been privy to hear their confidences. So you know, it began from some personal place and then it just went off. And next thing I know, I, I could tell you, I know where this came from and it’s not my life, but I know whose life it is. A lot of strands when I write I start from something heartfelt. I borrowed people’s dreams, the Bengal tiger dream. I borrowed someone’s nervous breakdown, borrowed watching a sparrow, take the dust bath.

You know, people tell you those things. And those are what I call buttons. And, you know, they’re just little schemes that you have with nothing that goes before and after. And when you need them, you’ve got your jar buttons. So, when you get stuck, look, look for your button jar. And that’s what I do.

Manuel Aragon: In the book, when Corina leaves Chicago and decides to head to Paris to chase her dream… I think for so many of us, especially when we’re from our communities, we dream of these places that we must go in order to be taken seriously as an artist.

Sandra Cisneros: Well, that’s because we don’t know how to become artists because our tíos and our comadres and mothers and fathers, or our cousin Louie can’t necessarily help us. And there’s nobody that can get you in, for those of us who don’t have those connections or didn’t grow up in New York, we’re clueless. You know, we look at the movies you know, we look at the dates at the closures of the prefaces of the city is where writers lived. So you think if you go to this city that you’ll find the key, you know.

I felt I needed to go to San Francisco where it was happening for Chicana writers. But once I got there, I said, no, this isn’t what I was dreaming of. The dream is wrong. I have to go back.

Manuel Aragon: As I read Martita, Corina feels like you to a point. And then it shifts and becomes, it’s an alternate reality version of you. I love thinking about it from that aspect because all of us have these moments that I guess are like, make or change it.

Sandra Cisneros: Well, I didn’t know where the story was going to take me. I had to wait 30 years to find it, to wait for the I character who was me, to take off and become not me.

Do you remember your childhood phone number (Sandra shares her number)? That’s funny, right? (She pretends to call the number) Am I there? Hello? Could I talk to you? Sort of like Martita.

Manuel Aragon: What are the projects that you’re focused on these days?

Sandra Cisneros: Okay. I just finished my book of poetry. And that’s coming out next fall. And I’m working on an opera with Derek Bermel of The House on Mango Street.

We’ve already premiered like a suite of the songs, but now we’ve expanded it. So we’ll see it performed and workshop it. So I hope it will be done soon. There’s a television show. It’s still in the initial stages. What else am I doing? I think those are some of the projects. I know there’s more, but I can’t think of it right now. Yeah.

I’m working on essays, and everybody always wants me to write a novel, but they don’t realize that writing a novel it’s like going, you know, volunteering to go to prison for 10 years. Why would you want to go to prison for 10 years? I know how long it’s going to take. So I was like, oh, don’t send me back to solitary confinement.

Manuel Aragon: Who are you currently reading?

Sandra Cisneros: Oh well, I’m rereading a lot of books. There’s a lot of things on my bedside right now. I’m reading Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz Loaded: A Disarming History of the Second Amendment. About the amendment, violence, and how our country got here.

I love Jaime Cortez’s Gordo that comes out this month at short stories. You’re going to love it. That’s such a good collection. I just laughed. I cried, you know, it was just painful and beautiful and really good writing.

I just saw a book by Alberto Ledesma Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer, a graphic novel about being an undocumented young person. Which lead me back to the poem Solito, Solita by Javier Zamora. And I had his book poetry, Unaccompanied, on my bedside too, but I’m rereading that.

I just thought of a writer that you might like since you liked short stories, Christine Granados, do you know her? She conjures El Paso in a really incredible way. And she’s one of those Texas writers that are ignored because they write short stories or they don’t publish the right genre, but she’s someone to watch.

Manuel Aragon: Well, thank you so much for giving me this time.

Sandra Cisneros: Thank you. Nice to meet you. I look forward to meeting you on the page.

***

Manuel Aragon is a Latinx writer, director, and filmmaker from Denver, CO. He is currently working on a short story collection, Norteñas. His work has appeared in ANMLY. His short story, “A Violent Noise,” was nominated for the 2020 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers. Twitter: @Spacejunc.