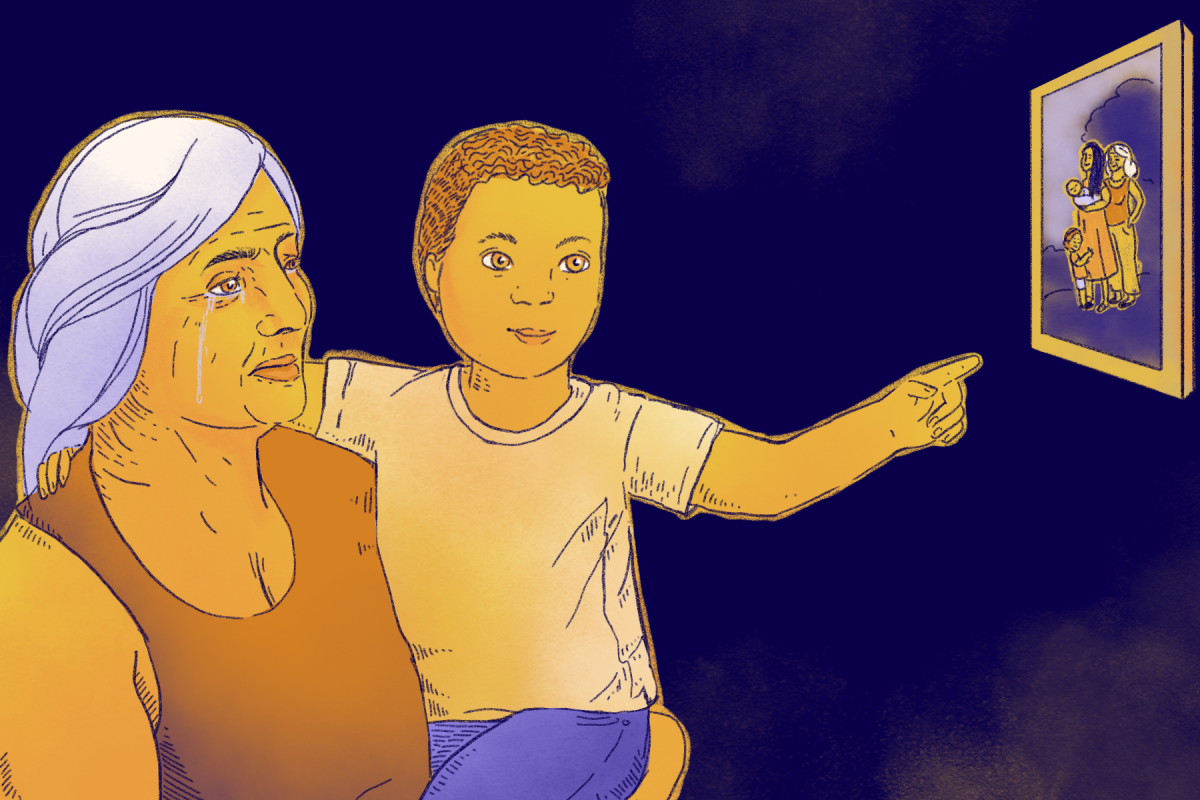

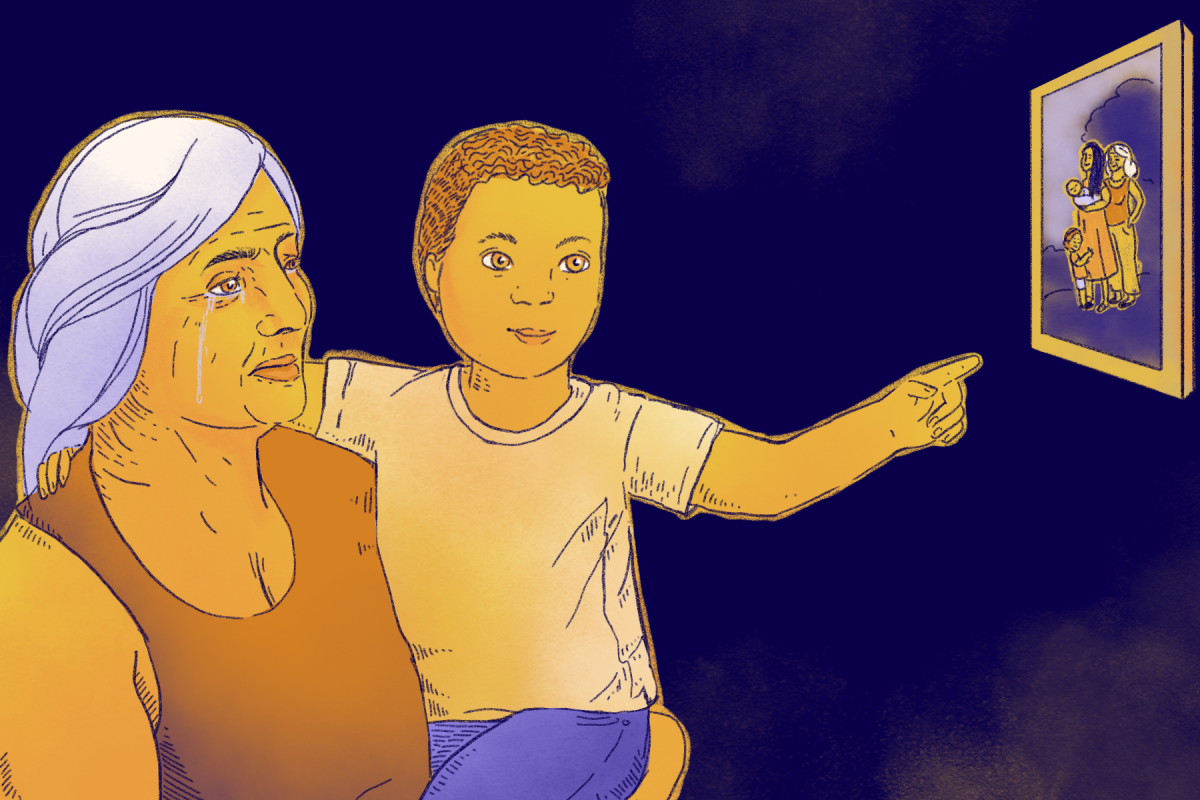

Press reports frequently state that grandmothers are left in charge of the children. (Adriana C. García Soto/Centro de Periodismo Investigativo/Todas)

By Cristina del Mar Quiles, Centro de Periodismo Investigativo and Todas

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico — Elba Santos had been searching for her daughter Angie Noemí González Santos for three days in the hills of Puerto Rico’s mountainous region when she got a text message from one of her granddaughters.

“Abuela, I’m scared,” the message read. “They took daddy to jail.” Santos, a 46-year-old Puerto Rican woman, moved to the United States after Hurricane María hit the Island, and she tells this story over the phone from her home in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

When Angie disappeared on January 14, 2021, Santos traveled to Puerto Rico to search for her. Her daughter was 29 years old and worked as an elderly caretaker.

Her three granddaughters, six, 10 and 13 years old, were at the police station at the time that their father, Roberto Félix Díaz, was arrested and taken to court to have charges filed for the murder of his wife. He, who had reported her missing days before, was the main suspect.

Santos took over the care of her three granddaughters from then on, as happens to many Puerto Rican grandmothers who deal with the same responsibility of raising the children of their daughters killed by gender violence.

In Puerto Rico, there are no reliable official statistics on the murders of women, nor are there figures that accurately reflect the impact of gender-based violence on surviving families. According to data collected by non-governmental organizations Kilómetro 0, Proyecto Matria, and the Gender Equity Observatory, since Hurricane María hit the island on September 20, 2017, 71 women have been murdered by their partners or ex-partners. Consequently, in that same period, at least 55 minors were orphaned, according to calculations by the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (CPI) and the digital media outlet Todas.

There is no official record of the custodial grandmothers of these minor survivors of femicides, as confirmed by the Department of Family. These grandmothers face the challenge of raising and dealing with the trauma of their grandchildren, in addition to their own loss, with little or no support from the government. Only news stories frequently confirm that grandmothers assume this responsibility.

An estimated 44 percent of the population in Puerto Rico live below the poverty level, according to 2019 data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Women between 55 and 64 years old are the second largest population group living below the poverty level on the island.

First, The Lack of empathy

A call from the police confirmed Santos’ greatest fears.

“Start making funeral arrangements,” said the officer investigating the disappearance of Angie Noemí. Her daughter had been murdered and her body was found at the bottom of a ravine in Coamo, in the south. Santos was shocked, not only by the terrible news, but by the crude way in which it was delivered.

“That’s what he told me. You can imagine that I went crazy! The phone fell about 10 feet from me. I started screaming, screaming, screaming. I didn’t know what to do or what to say,” she recalls.

Meanwhile, at the police station, Santos’ three granddaughters received the same news. Their mother was dead. A Department of Family social worker told them.

“The older one had a panic attack. The other two cried,” Santos learned.

The grandmother said that the Department of Family arranged for the girls to have psychological therapy once a week. In addition, the Department of Justice’s Office of Compensation and Services to Victims and Witnesses of Crimes awarded financial compensation to the minors and reimbursed the funeral expenses. The Office also offered psychological support to Santos, but she opted to continue receiving the services of psychology and psychiatry professionals that were already treating her in Connecticut.

Protocols for Emergency Custody

When a femicide happens that directly impacts minors, the Department of Family gets a referral that activates a social worker who is sent to the crime scene. Glenda Gerena, an administrator at the Department of the Family’s Administration of Families and Children (ADFAN), said the agency takes emergency custody of the minors for a period of 72 hours while an investigation is carried out to determine where they will be better placed. Often it is with a relative or in an agency-endorsed foster home.

Early in the intervention, the agency seeks a physical and psychological evaluation of the minors present in a femicide scene, Gerena said.

“The number of therapy sessions will depend on how severe the impact has been and what the behavior professional determines, in this case the psychologist,” she added.

Glenda Gerena, administrator of the Administration of Families and Children of the Department of the Family (Adriana C. García Soto/Centro de Periodismo Investigativo/Todas)

The agency does not have a special protocol for grandmothers who are left in charge of their grandchildren after their daughters are murdered in circumstances of domestic violence. Investigations and cases are handled according to the Manual of Norms, Procedures and Execution Standards on the Safety Model in the Investigation of Referrals of Child Abuse. It seeks to control the danger or threat of harm to a minor by establishing a protective action plan to ensure their well-being.

The mental health needs of grandmothers who take care of their grandchildren are considered as part of the family service plan, said Gerena

Social workers and family service technicians are responsible for identifying these needs and can also recommend counseling, psychological services, and make referrals to other agencies.

However, in the cases documented for this investigation, aside from the procedures related to the custody of minors after a femicide, and providing them with mental health services at times, the Department of the Family has been absent, according to the testimony of grandmothers who took care of their grandchildren when their daughters were murdered.

The First Weeks Are the Worst

The first weeks were horrible, Santos says. Since the pandemic began, in March 2020, the girls did not go to their school, located in the town of Orocovis in the central mountainous region, where they attended the first, fifth and eighth grades. Because they did not have internet in the house where they lived, the alternative was to complete the assignments that the teachers sent them on paper and follow some modules prepared by the Department of Education.

Santos faced a new reality overnight, that of raising children again, with all that it implies. As much as she could, she helped her granddaughters with schoolwork, but she was out of practice. “It was very hard for them. Thank God, the teachers helped them a lot and that’s how they were able to approve the grade,” she said.

Outside of school, the girls were publicly singled out. The disappearance of Angie Noemí and the confirmation of her murder were widely reported on the island’s news outlets for several days. It was the first femicide for domestic violence in 2021 and fueled claims for the declaration of a state of emergency in Puerto Rico.

“We couldn’t go to a restaurant, or a McDonald’s or a Burger King because they were quickly pointing them out and even taking pictures,” Santos said.

The process of getting custody of her granddaughters compounded the mourning for her daughter’s murder and the public curiosity. It took six months, after several court hearing cancellations. Santos believes the process could have been different, faster, and less traumatic.

In July, she proposed the possibility of moving to Bridgeport, Connecticut to her granddaughters and they agreed.

“They were willing and wanted to come. And that was the only thing I expected, that they go to school, that they like it and that they study, because they need an education to choose a career that they really like,” she said.

They have been in bilingual schools since August, facing the language challenge. The girls spoke Spanish and were not fluent in English before moving.

Santos’ days are spent getting her granddaughters ready for school, cleaning the house, doing homework, and trying to deal with three different personalities. In addition, she has another son who is 17 years old.

For the girls, the memory of their mother is very present. “The little one sleeps with me every night. If she’s not sleepy, she starts thinking about her [Angie Noemí]. She says, ‘Grandma, but why did he do that to my mom? My mom was good. My mom never hurt anyone.'”

Santos is aware that she and her granddaughters will carry the pain of her daughter’s murder for the rest of their lives. She says they must learn to live with loss. “We’re working on that.”

Grandmothers Who Take On Parenting Without Help

No public support alternative exists in Puerto Rico for the grandmothers who raise these children and teens while facing their own traumas.

“I’ve gotten no help. Everything I’ve done, I’ve done alone,” said Annette Quiñones, mother of Loren Figueroa Quiñones, who was murdered by her partner on June 30, 2018. “God has been my only psychologist.”

Quiñones also assumed responsibility for her grandson, who is now five years old and who, at the age of two, witnessed the crime. She relies on her job with a delivery company to meet their needs and counts on help from her three other adult children.

The grandmother sought psychological help for the child days after Loren’s femicide. She did it on her own, because aside from the process of getting the child’s custody with the Department of Family, she has not had other support from the government of Puerto Rico.

The psychologist recommended that she take him to therapy at the age of five, which he just recently turned. She said the appointment is already set.

“I work, but if I hadn’t been working, then I would go crazy,” she said about what it means to be her grandson’s main caregiver. She thinks about people who have no one to help them. “Because children need their food, their clothes, their bedding, their comfort … But the State kind of forgot this part.”

María Victoria Arroyo faces a similar situation. Her daughter, Annette García Arroyo, was murdered by her partner on July 19, 2018, and after the crime, Arroyo was left in charge of two granddaughters who are now 12 and 14 years old. She survives on the $200 monthly child support that the girls’ father, who lives in the United States, pays her, on her daughter Annette’s social security income, and on food stamps. She had to quit the job she had at a cousin’s street food place in Cabo Rojo, in southwestern Puerto Rico, when she was hit with her daughter’s killing.

In the months that followed the crime, Arroyo got mental health assistance that she arranged on her own with a town psychologist for her and her granddaughters, and that she paid for with the government’s health insurance plan. After a year of therapy, the psychologist refused to accept the public health plan to cover her services, and she gave up seeking help for herself while the girls began getting therapy from the school psychologist assigned to her school.

“I’ve had to hide my pain and keep quiet so that my granddaughters don’t suffer. I’ve had to block my suffering, but I still haven’t recovered,” says Arroyo.

A Pain That Few Can Understand

The male-dominated culture —and the gender stereotypes that it fosters— force these grandmothers to concentrate on their grandchildren’s needs, ignoring their own mental health, sometimes with consequences for their physical health, said Inés Rivera Colón, social worker and scholar of the subject of grandparents who take care of their grandchildren. Engaging in new routines presents challenges for someone who had no chance to prepare.

For Amaryllis Alvarado Guzmán, who co-wrote the book Abuelos y abuelas… padres y madres en segunda ronda with Rivera Colón, one of the main challenges is the generation gap between them and their grandchildren. It is not odd for many to suffer the frustration of thinking that they fall short of school expectations by helping children with their schoolwork, or for not keeping up with technology. This complication became much more apparent when the pandemic began, and classes moved to the virtual realm.

Puerto Rico’s Department of the Family does not have an official record of the custodial grandmothers of child survivors of femicides. (Adriana C. García Soto/Centro de Periodismo Investigativo/Todas)

Feelings of loneliness are added to the stressors associated with caring for grandchildren. Many feel that very few people can understand their pain, says Rivera Colón.

“It’s not the same to lose a child due to an illness or an accident, than to lose your daughter because a person who was her partner, who at some point declared feelings of love and affection, killed her,” she said.

She believes this aspect of the loss requires specific attention that should be part of a comprehensive plan against gender violence in Puerto Rico. Statistics need to be gathered for that specifically, she stressed.

Both professionals are founders of the Resonar organization, which provides educational and consulting services for grandparents raising grandchildren.

They agree that, in the current context, schools are the ideal setting to coordinate specific services for children who have lost their mothers because of sexist violence and for grandmothers who have had to take charge.

The Possibility of a Comprehensive Reparation

Specialized care initiatives for indirect victims of femicides must go hand in hand with reparations, says Debora Upegui, an analyst from the Gender Equity Observatory, a topic that is just starting to be discussed in Puerto Rico.

Upegui refers to the need of developing a public policy that, beyond counting the victims of femicides, educating against gender violence, and providing help so that women can get out of the cycles of violence, it also recognizes that the attention and care of the murdered women’s children and their guardians are the government’s responsibility. It has to do with what is known as comprehensive reparation, a claim that has had a greater echo in Latin American countries where indirect victims of femicides have more visibility.

“Something that should be provided is free education to the children of femicide victims because we believe that one of the most important things that can help someone have a better quality of life in the future is access to a college education,” Upegui said.

College scholarships are one of the comprehensive reparation measures that the Latin American Network Against Gender Violence included in its 2020 manifesto, as a requirement to the governments of the region to prevent, reduce, and eliminate this problem.

Other measures included as comprehensive reparations are housing vouchers, health care, loans, and seed funding for entrepreneurship.

In an interview with the CPI, prosecutor Ileana Espada, compliance officer of the Support, Rescue and Education Prevention Committee, agreed that the issue of college scholarships as a possibility of comprehensive reparation should be included as part of their report with proposals to the governor.

This type of aid, which currently exists in Puerto Rico for the children of police officers who have died in the line of duty, would not only be a measure to mitigate the disadvantage of children whose mothers were killed in a domestic violence context, but also a way to alleviate the financial burden that the grandmothers in charge would have to assume if their grandchildren aspire a college degree.

***

Cristina del Mar Quiles reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 Domestic Violence Impact Reporting Fund.