SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico — “A Puerto Rico without Puerto Ricans” has become almost cliche in talks concerning the current wave of gentrification washing over the islands. It’s a phrase so bold-faced about ridding the island of its native inhabitants that one is tempted to view it as satire, if the message behind it hadn’t become all too real for the people of Puerto Rico over the past decade.

If you type the phrase “Puerto Rico real estate” into any search engine, you’re bound to stumble upon a melangé of videos and articles promising to teach you how to best take advantage of the island’s tax incentives for foreigners. Some, like Flipping Master TV, claim “Puerto Rico is an absolute goldmine for real estate investing.”

They are all talking about Puerto Rico’s Act 60. Passed in 2019, it enables two other laws passed in 2012 that were specifically created to draw wealthy investors to the island.

The first, Act 20, stipulates that any export services campaign that establishes an office on the island can get a four percent corporate tax rate and full tax exemption on dividends. A company is not required to hire local Puerto Ricans unless its annual revenue exceeds $3 million, in which case it has to hire at least one.

Act 22, meanwhile, offers individuals a full exemption on all local taxes for passive income if they buy residential property, donate at least $10,000 to a local nonprofit, and live in Puerto Rico for at least 183 days per year to establish residence.

These tax incentives have inspired a wave of settlers to escape the comparatively stringent tax laws in the United States for Puerto Rico’s tropical paradise. Since Act 60 was first enacted, more than 4,500 individuals and businesses have relocated to the island, with the majority of them coming from the United States.

YouTuber-turned-boxer Logan Paul has become the poster child for this movement, after announcing his plans to move to the island during an episode of his Impaulsive podcast. Paul would have been paying a 37 percent capital gains tax in Los Angeles, but thanks to Act 60 tax incentives, he pays nothing.

Logan Paul and his younger brother and fellow YouTuber-turned-boxer Jake Paul moved into a $10 million dollar home in Dorado Beach. Almost immediately after moving there, Jake Paul got into hot water with Puerto Rican authorities after he published a video of him driving a motorized vehicle along the beach, which is prohibited since the beach serves as a natural habitat for an endangered species of turtle.

Uno queriendo estar tranquilo y se encuentra con este video de Jake Paul destruyendo nuestras playas. #JakePaulGoHome pic.twitter.com/BiAhOCt7W3

— Robinson Camacho Rodríguez (@RobiCamacho) May 13, 2021

A report released by the Department of Economic Development and Commerce (DDEC) revealed that Dorado is one of the top five destinations for those who received Act 60 decrees. The municipality, where a mansion recently sold for $30 million, has always catered to the island’s richest inhabitants, but Act 60 has only exacerbated the disparity between it and the rest of the island. A drive through the quaint beachside town shows that most of these palatial homes are kept behind multiple gates and security walls with their own private access to the beach.

The government has championed these tax incentives since their inception, claiming they’re essential to paying off the island’s $70 billion debt. (On Tuesday, January 18, U.S. District Judge Laura Taylor Swain signed an adjustment plan that will shave about $26 billion of that debt.) The archipelago has been in an economic recession since before Act 60 was instituted, thanks to the repeal of Section 936 of the U.S. tax code, which granted U.S. corporations a tax exemption on income generated in a U.S. territory, such as Puerto Rico. Now Puerto Rico has an unemployment rate that hovers around 7.8 percent, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

While the government favors these laws, many Puerto Ricans have harshly criticized them because they further enforce a colonial status on Puerto Rico. Most who criticize the law point to the fact that the money generated by these laws rarely leaves the rich communities established by non-Puerto Ricans . While the ultra-rich bask in the wealth afforded to them by lower or no taxes, Puerto Ricans contend with increasing rent and electrical prices, while many public services are receiving less funding than ever before.

While Act 20 has seemingly had an impact on the economy, many question whether Act 22 adds anything to the economy. A report by the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo found that the majority of Act 22 grantees “barely create jobs and represent minimal impact on the local economy.”

“I don’t think attracting tax avoiders is a good thing,” said Nobel Laureate in Economics Joseph Stiglitz while speaking at the Public Growth Policy Summit last December. “Rather than bringing in revenue, they are raising the cost of living.”

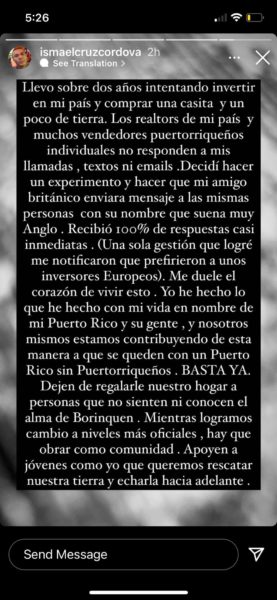

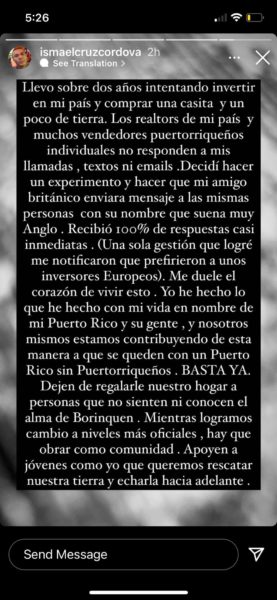

Screenshot of Ismael Cruz Cordova’s post on Instagram in which he details his attempts to invest in real estate in his homeland. (Ismael Cruz Cordova/ Instagram)

“The realtors of my country and a lot of individual Puerto Rican vendors don’t respond to my calls, texts nor emails,” said Ismael Cruz Cordova in post on Instagram. The young Puerto Rican actor currently resides in the United States and wanted to “invest in his country” by buying “a little house and a bit of land” to call his own. He conducted “an experiment” in which he asked a British friend with a ” very Anglo-sounding name” to call the same vendors. His friend got callbacks from every one “almost immediately.”

Many others have faced similar circumstances when trying to return to the archipelago after leaving to pursue better job opportunities not afforded to them by Puerto Rico’s rapidly constricting economy.

Pablo Defendini, reacting to Cruz Cordova’s message, posted an email exchange he had with a Puerto Rican realtor, who asked if he spoke English after Defendini wrote him in Spanish. “If I speak to them in Spanish they blow me off; if I speak in English no,” he tweeted. His post was met with others sharing their own experiences of being disregarded in favor of English-speaking renters or buyers.

Esto me está pasando a mi, ahora, que estoy buscando apartamento en San Juan. Si les hablo en español me pichean; si les hablo en inglés no. https://t.co/e40g1ml34u pic.twitter.com/hthWbiTEtY

— Pablo Defendini (@pablod) January 3, 2022

Meanwhile, in private Facebook groups like Act 60 / 20 / 22 Puerto Rico Tax Incentive Forum (Heavily Moderated) and Puerto Rico Act 20 / 22 Real Estate, there are dozens of properties listed at exorbitant prices. Among these, the most eye-catching to the Puerto Rican public has been the sale of lands bordering the archipelago’s tropical forest. A “spectacular 225 acres of land” at the foot of El Yunque National Forest were recently sold for more than $2.2 million dollars. El “Charco del Hippie,” a popular swimming hole in the area frequented by hundreds of families on the weekends, was one of the main selling points for the property. The advertisement explicitly stated that it was ideal for “short term rentals” and that tax incentives for Act 20 and Act 22 investors could apply.

Browsing Airbnb shows that a substantial amount of the archipelago’s apartments and houses have been converted into short-term rentals by tax incentive grantees. Many of these are priced at more than $80 per night, far out of the price range for most Puerto Ricans, over 40 percent of whom live below the poverty line. Clearly, such properties are geared to Puerto Rico’s wealthy elite who, thanks to the incentives, are primarily foreigners.

Gov. Pedro Pierluisi has maintained that the incentives help the archipelago and its people. But he’s faced harsh criticism due to the financial gains his family has enjoyed because of the law. His daughter-in-law Blanca Hebé Pierluisi, a real estate agent, is the administrator for the private Facebook group Act 20/22 – Puerto Rico Real Estate Guide. Meant to “inform individuals of the local real estate practices in Puerto Rico,” the group boasts 5,000 members. Some comments implore her to speak to her father-in-law to “stand up to the IRS” and block audits of their tax incentive grantee status.

Such Facebook groups, which rapidly became private after facing criticism from Puerto Ricans, are the main space where Act 60 grantees congregate to share tips and advice. But there are more sinister features to these groups. One group proudly claims it will ban anyone who attempts to “shame a decree holder into silence based on their perceived racism, prejudice, colonialism, stereoptypes [sic], hateful statements/opinions.” Another group posted a person asking if it was “racist” to pay Puerto Ricans less than their American counterparts because of the local job market.

@coquitomami There’s so much more to this issue. This only scratches the surface. Support & listen to boricuas?? #greenscreen #puertorico #colonialism #mifamilia

The comment making the case that Pierluisi “stand up to the IRS” because “tax decree holders did a lot to get him elected” highlights a mounting concern for many Puerto Ricans, in that investors and their money hold increasing sway over the archipelago’s politics going forward.

Ultimately, the influx of rich foreigners brought to Puerto Rico —and the exodus of Puerto Ricans not afforded the same luxuries as their foreign counterparts— has caused a displacement crisis with no end in sight. The archipelago’s government continues to cater to Act 60 grantees, making it so that places like Dorado, Palmas del Mar and Rincón are well maintained while the parts of Puerto Rico where locals who don’t apply for tax incentives live —and where their families have lived for generations— continue falling deeper and deeper into disarray.

“A Puerto Rico without Puerto Ricans” is becoming more of a reality every day.

***

Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco is a freelance journalist, mostly focused on civil unrest, extremism, and political corruption. Twitter: @Vaquero2XL

You are addressing the issues true and real, but think, the other people, not Puerto Rican, like me, who bought a modest home will contribute to the economy, I will eat in your restaurants, shop at your mom’s store, buy furniture at your brother’s store, I am respectful and try to fit in, on this beautiful island.

It is your government that is selling out Puerto Rico, it is your Governor who has a zero program, helping not rich people of the island being able to acquire a home.

You can’t stop greed, but you can control it. Elect a Governor that represents you and how you want your island to be.

Trust me, Pierluisi is hugging the rich and the previous Governors almost killed Puerto Rico!

its not going to attract millions like we have to put up with here. here on the mainland we are being told to deal with millions coming uninvited and mostly unwanted. we have to pay higher taxes to help feed, educate and house these people. this is the future we are being told. now its hitting home. its not pretty.

bec of the millions coming to the states for the benefits we now have million of low income citizens suffering bec there are only so many benefits and jobs to go around.

You wrote “A company is not required to hire local Puerto Ricans unless its annual revenue exceeds $3 million, in which case it has to hire at least one.” Actually, if they’re annual revenue exceeds $3mil then they are required to hire at least one “local” and since it is a requirement for them to become bonafide residents, then the decree holders themselves are considered “local” and so many of them, most of them, hire themselves to be in compliance. They are not required to hire any Puerto Ricans at all, under no circumstances, just one ‘local’ – which can be them or their spouse, or their child, etc. So when you read the number of jobs that have been created under the acts, remember that many, if not most of those jobs they created are actually for themselves. Their contribution is minimal. It’s a horrible deal for the Puerto Ricans. These incentives do vastly more harm than good for the Puerto Rican people on the island.

[…] with incentive laws, has spurred an increase in property value and is one of the reasons for the displacement acceleration. This adds to what he considers an endemic problem: the gap between the median home price on the […]

[…] has also been displacement of locals by overseas buyers shopping for up land, getting edge of the controversial Act 60 searching for effective tax breaks offered by the government. The lack of a delivery area, or in […]

[…] has also been displacement of locals by foreign investors buying up land, taking advantage of the controversial Act 60 looking for beneficial tax breaks offered by the government. The lack of a delivery room, or indeed […]

[…] has also been displacement of locals by foreign investors buying up land, taking advantage of the controversial Act 60 looking for beneficial tax breaks offered by the government. The lack of a delivery room, or indeed […]

[…] has also been displacement of locals by foreign investors buying up land, taking advantage of the controversial Act 60 looking for beneficial tax breaks offered by the government. The lack of a delivery room, or indeed […]

[…] been displacement of locals by international buyers shopping for up land, profiting from the controversial Act 60 in search of helpful tax breaks provided by the authorities. The lack of a supply room, or […]

[…] on its knees to real estate predators and the ultra-rich by supercharging a tax incentive law, Act 60 (former Act 22). As a result, Puerto Rican communities are being subjected to break-neck […]

[…] up the island of Gathia to real estate scammers and the super-rich by imposing a tax incentive law. Law 60 (Previous Law 22). As a result, Puerto Rican communities are subjected to a harsh process of […]

[…] on its knees to real estate predators and the ultra-rich by supercharging a tax incentive law, Act 60 (former Act 22). As a result, Puerto Rican communities are being subjected to break-neck […]

[…] knees to actual property predators and the ultra-rich by supercharging a tax incentive legislation, Act 60 (former Act 22). Because of this, Puerto Rican communities are being subjected to break-neck […]

[…] aux prédateurs immobiliers et aux ultra-riches en imposant une loi d’incitation fiscale, Acte 60 (ancienne loi 22). En conséquence, les communautés portoricaines sont soumises à une […]

[…] और अति-अमीरों के लिए एक द्वीप खोल दिया, अधिनियम 60 (पूर्व अधिनियम 22)। परिणामस्वरूप, […]

[…] on its knees to real estate predators and the ultra-rich by supercharging a tax incentive law, Act 60 (former Act 22). As a result, Puerto Rican communities are being subjected to break-neck […]

[…] on its knees to real estate predators and the ultra-rich by supercharging a tax incentive law, Act 60 (former Act 22). As a result, Puerto Rican communities are being subjected to break-neck […]

[…] up the island of Gathia to real estate scammers and the super-rich by imposing a tax incentive law. Law 60 (Previous Law 22). As a result, Puerto Rican communities are subjected to a harsh process of […]