Jimmy Badillo thinks back to his childhood with pain. The son of Puerto Rican migrants, Badillo was born in the South Bronx, the youngest of six siblings. With an abusive father and an absent mother, Badillo didn’t like spending time at home, so he sought love and attention on the streets of New York City.

He would classify his upbringing as ordinary. The friends Badillo hung out with faced similar experiences of frustration, abandonment, and loneliness. To get out of a difficult home, they found relief elsewhere.

“I was practically raised with the dealers and the winners and the pushers and the prostitutes—the people of the street,” Badillo said. “That’s where I was getting my love from. When I felt like I wasn’t getting it at home, I was getting it en la calle“—in the street.

Getting Hooked

Badillo wasn’t supposed to be born. Growing up, his older siblings would tell him how his parents didn’t want a sixth child. After his father found out that his mother was pregnant, he would physically assault her and try to get her to abort her baby.

Badillo felt unwanted from the get-go, but he eventually understood that he wasn’t a burden. He was a miracle. It would take him more than three decades to come to that realization.

A few years after he was born, Badillo and his family relocated to the Lower East Side in search of better economic opportunities. One of his earliest memories from that period happened on Avenue D and Third Street. It was 1975. Badillo was 10 years old and roaming the area with his friends when they saw police officers chasing a man on a motorcycle. He threw away a brown paper bag before speeding off. Badillo ran up to it, wanting to see if there was any money inside. Instead, he found small bags of heroin. Curious, he and his friends pulled them out and inspected them. Then they decided to try them.

“When I had that first feeling, it was a done deal. I was off to the races,” said Badillo, now 58. “I knew right then and there that could be something I could keep using to not hear my mother and father fighting, my father beating the mess out of my mother, or all the chaos. I’ll just sleep it off.”

Measuring the Drug Crisis

Badillo’s story of drug use and poverty is common among many individuals inside the Bronx community—especially Puerto Ricans. New York City has the largest concentration of Puerto Ricans in the country. In 2010, there were over 723,600 Puerto Ricans in the city, according to the latest U.S. Census data, with the Bronx boasting the highest density.

Over the years, Puerto Ricans migrated to New York City for many reasons, among them to reunite with family members, flee economic and political instability, and rebuild lives that were shattered by natural disasters back in the islands.

“This is why it impacts los boricuas,” said Badillo, using the colloquial term for Puerto Ricans. “It’s a poor man’s drug.”

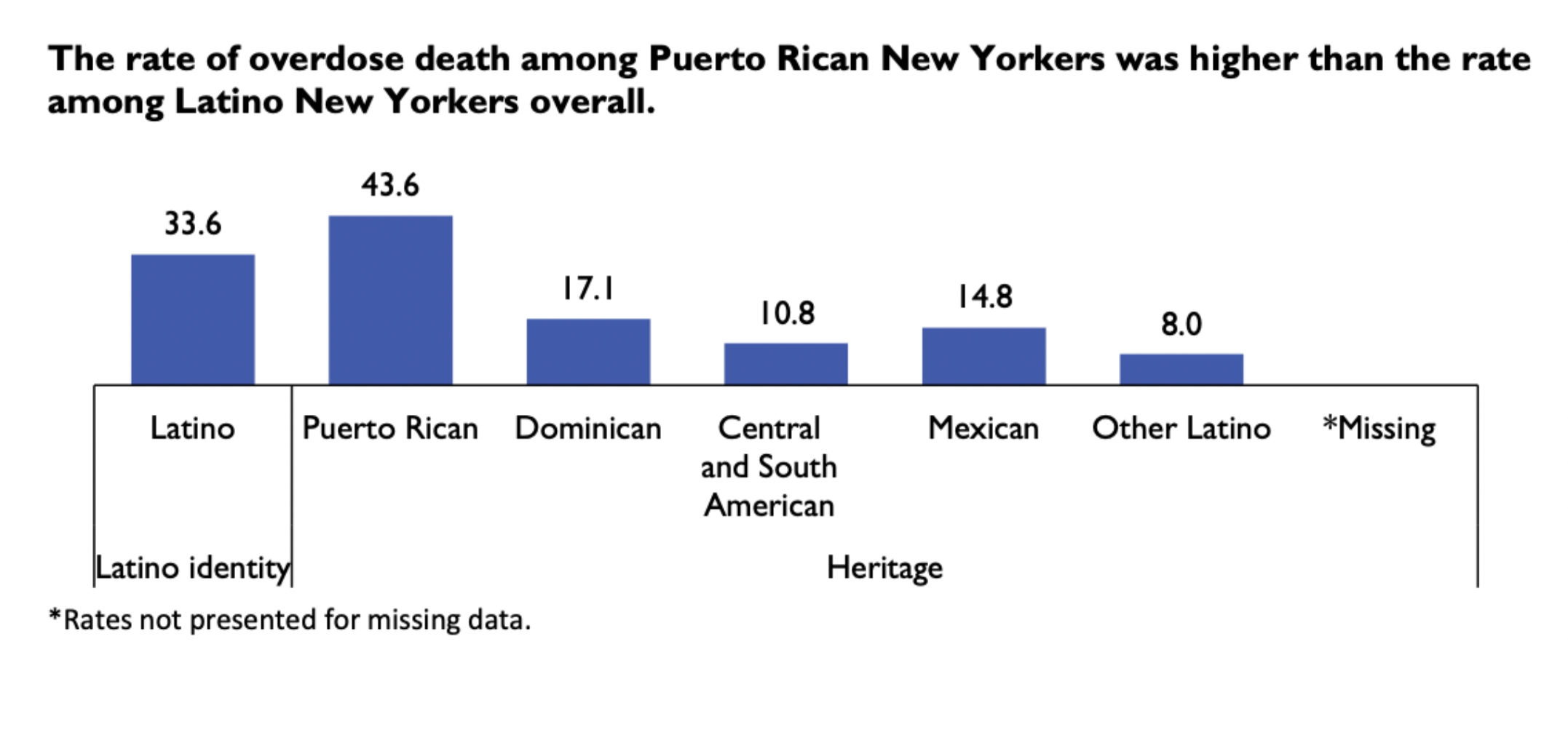

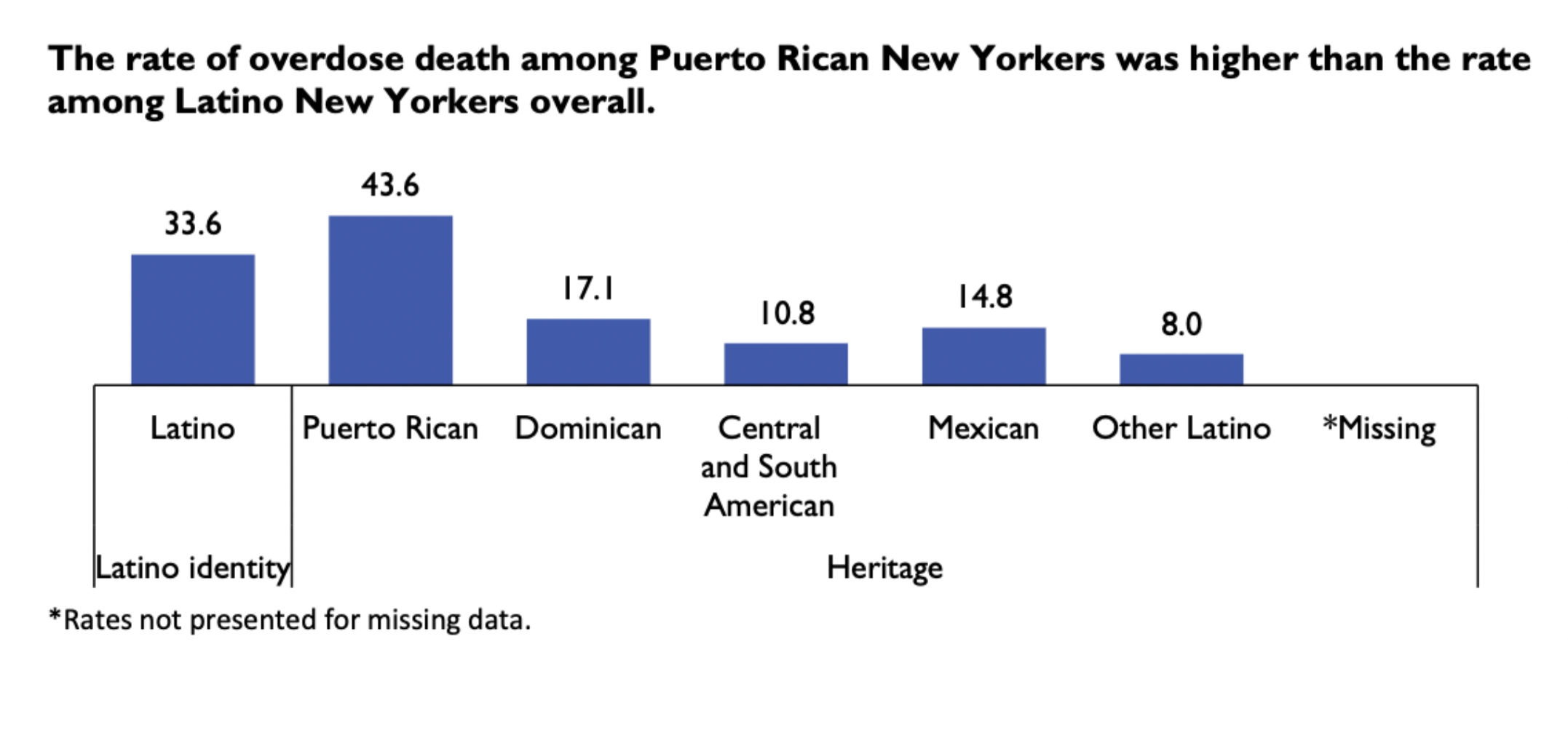

But the actual magnitude of heroin use within the Puerto Rican community in New York City has largely gone underrepresented. City data categorizes opioid use statistics into general demographics like Latino, Black, or Caucasian. But the category “Latino” can mean many things, and it shouldn’t be compressed into one uniform group because it runs the risk of undermining the impacts on one specific demographic.

In New York, the Latino community represents more than 20 unique countries of origin or other heritage groups, according to data from the Department of Health. Puerto Ricans are just one of many.

“We are pushing really hard for the New York City Department of Health to disaggregate ethnicity data to specify Latinx groups,” said Camila Gelpí-Acosta, a researcher at the City University of New York. “It’s an abstract, misleading category that doesn’t help anyone—Latinx people are extremely heterogeneous.”

It was only until recently that the city released disaggregated information for the first time, after people like Gelpí-Acosta had been pushing for the move for years.

The Department of Health carried out a 2020 survey analyzing overdose deaths among Latino New Yorkers, and the results spoke for themselves: Puerto Ricans represented the highest number of opioid deaths by a landslide. Out of 635 reported fatal overdoses, 232 were Puerto Ricans, followed by Dominicans, who only accounted for 89 of such deaths.

The rate of overdose deaths among Puerto Rican New Yorkers was higher than the rate among Latino New Yorkers overall.

Source: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

“This is about saving lives, and we can’t save lives if we don’t know who we are targeting,” said Gelpí-Acosta.

Gelpí-Acosta’s research spans more than 20 years of study both in Puerto Rico and in New York City. One of her studies on injection risk norms and practices among migrant Puerto Ricans who inject drugs in New York City found that, from 2000 to 2015, Puerto Ricans were at the highest risk of overdose, accounting for 67 percent of all overdose deaths.

Gelpí-Acosta, who is originally from Puerto Rico, founded her own harm reduction center in the island 14 years ago. Her research is unique, and today she continues to spearhead comparative studies on the opioid crisis and its impact on the Puerto Rican community.

Getting Clean

In 2002, during his second time in prison, Badillo experienced hope for the first time in the form of a person. He enrolled in GED classes to alleviate some of the boredom he experienced. At the time, Badillo had a fifth-grade reading level and difficulty writing and doing math. He was disinterested and amused himself by throwing books around to get a reaction out of his professor.

“He wanted to teach me in the midst of the anger and all the things I would do to discourage him from being next to me,” Badillo said. “His resilience to not stop and just see right through what I was trying to portray, and to see the little boy hurt and scared inside of me, made me say, ‘Hey, this guy cares enough about me, let me give him a chance.’”

But it was actually Badillo who was given a chance. His recovery process started around that time, and he soon began experiencing major withdrawals. The prison administration declined to facilitate his rehabilitation, so Badillo had to stop using cold turkey.

“It was hardcore. I thought I was going to die in there,” he recalled. “But there was this nurse called Mrs. B who would always be there and pray with me. When I would throw up, she would bring me crackers and bread.”

Along the way, he found his major source of hope: God. At the time, Badillo was facing a 15-to-30-year prison sentence.

“I did one thing I never did in my life, which is bow down and pray to God,” he said.

Shortly after, Badillo was resentenced and released after serving only three and a half years. His sense of hope continued to grow. When he was released in 2005, Badillo came out with a different mindset and a new purpose that involved continuous drug counseling, learning new coping mechanisms, and developing a social support network.

After almost a year into his release, Badillo regained custody of his eldest son. Two years after that, he was reunited with all three of his boys.

Today, Badillo lives in Dutchess County with his wife and continues a life of recovery. In 2016, he became a staff member at Cru Inner City, a faith-based organization that partners with inner-city churches to provide support and resources to vulnerable communities.

Every day, Badillo, who currently works as a project coordinator, travels to different boroughs in New York City to help people who lead lives like the one he used to live.

“I don’t have to be a product of my environment, and I refuse to,” he said. “When I realized that someone cared enough about me, it made me realize I don’t have to die in the streets. I don’t have to get high if I want to escape from something. I can go speak to another brother going through something.”

Though Badillo managed to recover, many of the issues he experienced linger today. Through his ministry work, he continues to see drug use, domestic violence, poverty, and loneliness in the same neighborhoods he grew up in.

“I think the only thing that changed is the time of day—literally,” he said. “It’s the same concept.”

Badillo believes the only people who can fix the deeply entrenched issues of drug use and poverty in the Bronx are the community members themselves. And he’s not the only one who shares this approach.

Tackling the Crisis

Every weekend, including holidays, Tamara Oyola-Santiago and Alexis del Río rent a car and fill the back with boxes stuffed with kits containing sterile syringes, fentanyl testing strips, Narcan, and wound care items. They head over to their local church at around six in the morning and pick up pre-packaged meals. Then they hit the streets of the Bronx, targeting abandoned buildings, overpasses, public parks, and secluded areas, where people who inject drugs tend to be.

Originally from Puerto Rico, Oyola-Santiago and del Río started working in the harm reduction sector in the capital city of San Juan, before relocating to New York City in 2007. When they moved to the Bronx, they quickly recognized the disproportionate impact that injection drug use had on Puerto Ricans.

In 2018, with nothing changing and overdose numbers only increasing, they decided to take matters into their own hands. Together with the help of Nelson González they founded Bronx Móvil. This harm-reduction program on wheels, which initially received no government funding, distributes essential services and resources to individuals impacted by the opioid crisis in the Bronx.

“This is a project that I felt has been maturing in our minds since we migrated,” said Oyola-Santiago. “The lack of culturally and linguistically centered care, the lack of 24/7 harm reduction, the lack of harm-reduction services that were mobile—we witnessed that from the get-go.”

Bronx Móvil has since served as a safety net for people who inject drugs when city harm-reduction initiatives and non-profits can’t provide around-the-clock care for an around-the-clock disease. Most harm-reduction programs across New York City are only open from Monday through Friday, and they tend to close at 5 p.m. During holidays, they remain closed.

“What we’re doing is the most logical approach,” del Río said.

Of all of Bronx Móvil’s participants, between 70 and 80 percent are Puerto Rican. Some are native New Yorkers with Puerto Rican heritage, while others migrated from the island.

The leaders of Bronx Móvil strategically plan the routes they take when they go into the community, specifically targeting neighborhoods that are disproportionately impacted by the opioid crisis. Among them are Mott Haven and the Hub in the South Bronx, plus Kingsbridge in the northern point of the borough.

Like Badillo, the members of Bronx Móvil agree that action must be taken now, with or without sufficient resources or support from the New York City Department of Health.

“We operate when we know there are either limited or no services, and we are mobile because we are literally meeting people where they are at,” Oyola-Santiago said. “And we’re also meeting people where they’re at mentally, psychologically, and culturally.”

Badillo wants to give support to those that can’t get it from anywhere else. He says the root of all issues is usually a lack of love.

“When I went through my transition, I thought that God was going to pick me up from hell, which he did, and drop me off in the Hamptons somewhere,” Badillo said. “But he dropped me off exactly where he picked me up—but this time I was fully equipped.”

Badillo repurposed his story and now defines his life as a miracle. Under the worst circumstances, he eventually fueled his outcome with hope and love.

Through his work and his story, Badillo wants to continue making miracles happen.

“When people see us, they know there’s hope there. They know that with Jimmy, they’re not going to get a bag of dope—they’re going to get a hug, they’re going to get an ear to listen to,” he said. “They just want to be heard.”

***

Camila Grigera Naón is an Argentine-American journalist and currently a student at Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia University. Twitter: @c_grigera

[…] Credit: Source link […]