This article is the second in a three-part series looking at the attempts made by Pedro Albizu Campos and other local leaders in Puerto Rico to hold a constitutional convention in 1936—the closest the archipelago has come to breaking free of U.S. colonial rule.

It seems clear that, for Pedro Albizu Campos, leader of Puerto Rico’s Nationalist Party, all roads led to a constitutional convention—to the establishment of the Republic of Puerto Rico through a national democratic process in which elected delegates were granted the power to begin drafting both the Constitution of Puerto Rico and the conditions of a treaty to be discussed with U.S. officials.

This is an important distinction to make about Don Pedro’s political thought. Rightfully distinguished as a proponent of armed struggle in favor of national liberation, the use of violence cannot be considered his be-all and end-all considering his focus on a constitutional convention as part of the decolonization process.

Just how close Don Pedro was to effecting a constitutional convention in 1936 is truly extraordinary and worthy of a closer look.

Support for the Constitutional Convention Movement

That there was in 1936 a bonafide movement in Puerto Rico in favor of holding a constitutional convention and establishing the Republic of Puerto Rico is without question. Not only was there expressed support, but there was intentional organizing at a national level.

On May 4, less than two weeks after the Tydings Bill was introduced, several hundred people, including intellectuals and representatives from civil, social, and cultural groups, held an assembly in the Ateneo Puertorriqueño, Puerto Rico’s most preeminent cultural institution. The assembly resulted in the formation of the Frente Unido por la Constitución de la República, a broad front that regularly engaged leaders from all of Puerto Rico’s political parties in addition to other groups and organizations. The United Front’s first major public event took place the following week on May 10 in Caguas and saw about 10,000 people in attendance, with as many as 350,000 tuning in to the radio broadcast.

Newspapers began to publish almost daily accounts of events related to the constitutional convention movement. Young people were particularly active during this period. The symbolic lowering of the U.S. flag and the raising of the Puerto Rican flag became a regular occurrence, taking place at the University of Puerto Rico and other schools and prominent locations. During one instance on May 12 at Santurce’s Central High School that received front-page coverage, police clubbed students, used tear gas, and fired shots into the air before the U.S.-appointed Gov. Blanton Winship mobilized two National Guard units to intervene.

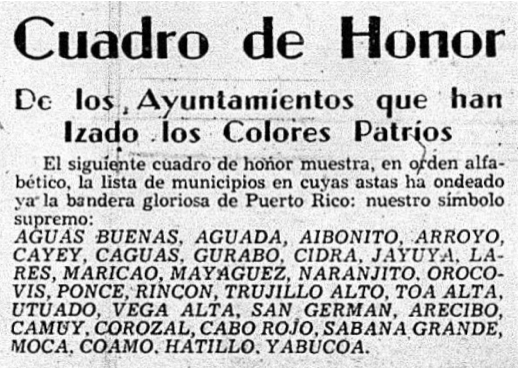

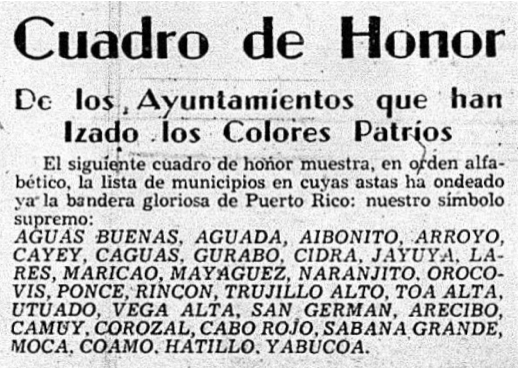

Also on May 12, the newspaper El Imparcial published a list of 30 municipalities where the Puerto Rican flag was raised in front of the local city hall. Notorious for its strong pro-independence stance despite its self-styled impartiality —the paper’s editor had been president of the Nationalist Party before Don Pedro took over in 1930— El Imparcial had started this “honor roll” in the days following the Tydings Bill, saluting more and more towns that expressed their independentismo almost every day.

In a regular column headlined “Honor Roll,” the pro-independence Puerto Rican newspaper El Imparcial celebrates the raising of the Puerto Rican flag in towns across the colony, on May 12, 1936. (Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, CUNY)

The founder of the Nationalist Party, José Coll y Cuchí, called on the public to perform such displays of patriotism in support of the convention movement in an article published on April 28, urging Puerto Ricans to raise the monoestrellada at their homes, workplaces, and anywhere they could.

How Colonialism Blocked Independence

The atmosphere presented Don Pedro with an incredible opportunity to push the Puerto Rican people to assert their nationhood. He described Puerto Rico as a legally constituted nation that had been occupied militarily by the United States since 1898.

A Harvard-educated lawyer who had studied international law, Don Pedro’s based his argument on an article in the Autonomous Charter granted to Puerto Rico by Spain in 1897 that had declared the Constitution of Puerto Rico unalterable “except by virtue of a law and at the request of the Insular Parliament.” In light of this, Don Pedro reasoned the following concerned the Treaty of Paris of 1898, which ended the Spanish-American War and resulted in Spain ceding Puerto Rico to the United States:

“Said treaty is null and void as far as Puerto Rico is concerned… The Treaty of Paris was not negotiated by the plenipotentiaries of Puerto Rico and was never submitted for ratification by our National Parliament.

“The Commander of the Yankee invaders feigned, at first, respect for our national Government and Parliament, but finally took off the mask and dissolved both by force. Since then Puerto Rico has been under the military intervention of the United States.”

Don Pedro had been considered a person of interest by U.S. authorities for some years prior to the 1936 constitutional convention movement. Plans to aggressively neutralize the Nationalist Party seem to have begun in earnest with a series of political appointments beginning in October 1933, when U.S. Army Colonel E. Francis Riggs, whose work in Nicaragua advising future dictator Anastasio Somoza resulted in the assassination of nationalist opposition leader Augusto Sandino, was made chief of police. In January 1934, former U.S. Army Gen. Blanton Winship was appointed governor of Puerto Rico, with former Gov. James Beverly providing a letter of recommendation in which he said Winship had “the necessary toughness to fulfill his duty, the same if it is favored by public opinion or not.” Also appointed during this period were both a prosecutor and a judge for the District Court of Puerto Rico, Aaron Cecil Snyder and Robert Archer Cooper, respectively.

U.S. authorities finally began the legal prosecution of Don Pedro on March 5, 1936, when they arrested him on the charge of seditious conspiracy. This came almost two months before the Tydings Bill was introduced in Congress and the constitutional convention movement got underway. Nevertheless, it can be presumed that the desire of colonial authorities to imprison Don Pedro became even greater once the bill created an unexpected outpouring of public sentiment in favor of independence—and especially in the moment that Don Pedro was receiving considerable publicity from his trial.

Reports from the U.S. military point directly to the interest the colonial authorities had in staying updated on everything taking place. In his weekly report on “Subversive Activities” dated May 7, 1936, Colonel Otis R. Cole, commander of the 65th Infantry Regiment in Puerto Rico, wrote:

“It is believed that if the bill is passed by Congress and the plebiscite held, an overwhelming majority of the Puerto Ricans will vote in favor of independence… If independence is granted to Puerto Rico, the ensuing lack of organization of the government during the beginnings of its independent life, together with the terroristic methods used by the Nationalists, will give Albizu Campos more than a fair chance of becoming the head of government.”

Intent on putting Don Pedro in prison, a second jury composed of 10 Americans and two Puerto Ricans was hand-selected by the prosecution after an initial jury of six Puerto Ricans and five Americans could not arrive at an agreement concerning the verdict. On July 31, the new jurors delivered their verdict: guilty.

It is easy to question the timing of Don Pedro’s conviction and wonder if it was at all connected to his success in calling for a constitutional convention and being the leader of a growing movement for independence. Don Pedro himself seems to have felt the timing of his conviction was not coincidental. When visited by his wife in jail before being sent to Atlanta Penitentiary, Don Pedro said the U.S. knew what they had in their hands. “If they had left me six more months in the streets I would have made the Republic.”

With Don Pedro in prison, his influence over both the Nationalist Party and the constitutional convention movement was greatly weakened. As the November elections approached, political leaders fully committed to the electoral campaigning they had already begun to place focus on. The convention movement faded into history.

Fearing the increasing displays of nationalistic pride sweeping across Puerto Rico in 1936, colonial authorities derailed that year’s constitutional convention movement to establish the Republic of Puerto Rico, thus ensuring U.S. colonialism would endure. In the 10 years after the movement was defeated, the Partido Popular Democrático was founded and the “Commonwealth” status was developed by its leader, Luis Muñoz Marín.

—

You can help raise funds for the author’s next project, a book of translations of Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos’ writings, by donating to and sharing his GoFundMe campaign.

***

Andre Lee Muniz is a Boricua from the projects of South Brooklyn, the creator of Remembering Don Pedro, and the author of ‘Vida y Hacienda: The Life and Legacy of Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos.’ Instagram: @RememberingDonPedro