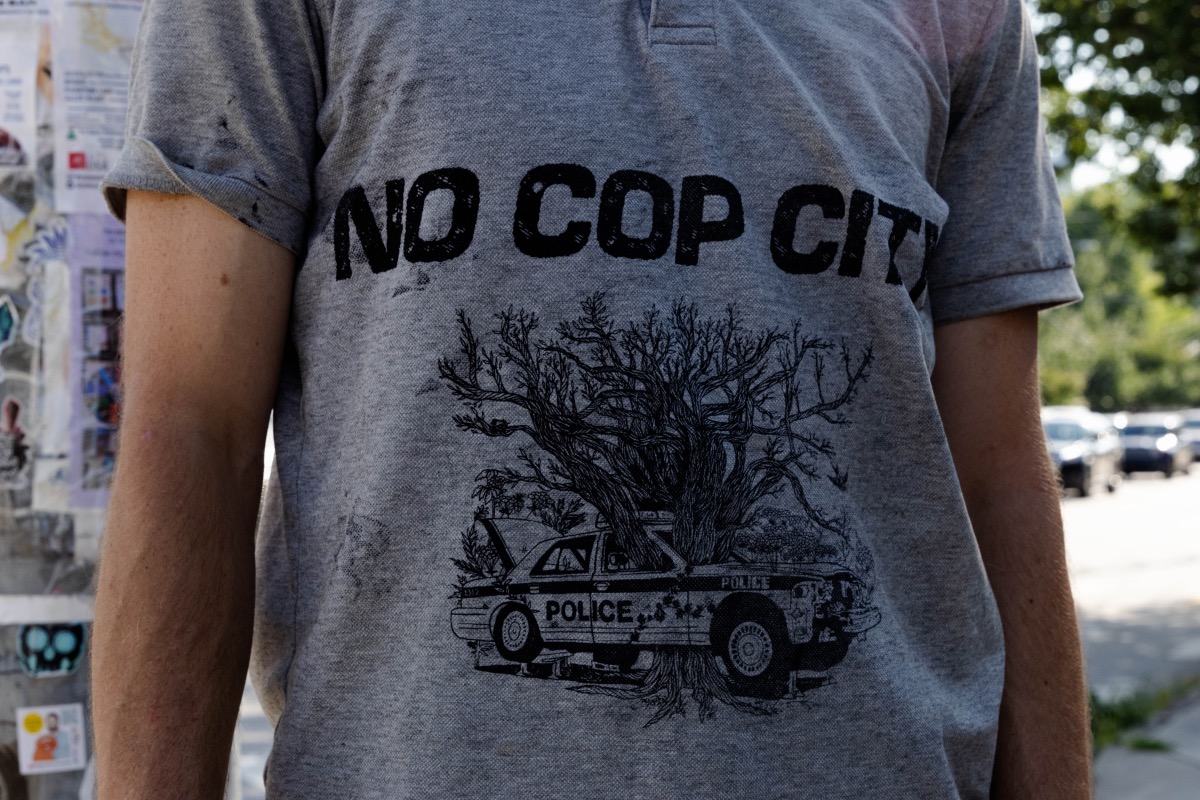

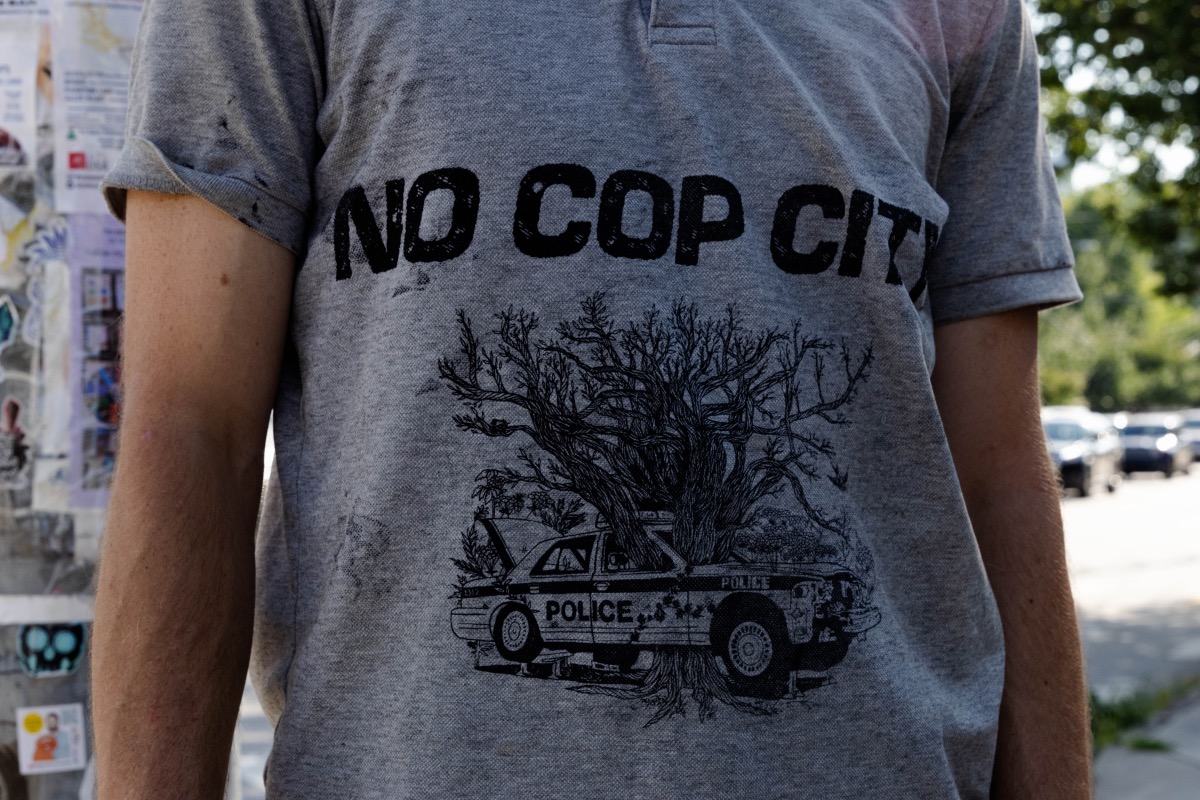

An activist wears a “No Cop City” t-shirt at a “Slow Roll for Tort” event in Atlanta, Georgia. “Slow Roll for Tort” events have become a weekly event for cyclists attempting to keep alive the memory of slain activist Manuel “Tortuguita” Esteban Paez Terán as they protest the construction of a $90 million police training facility known as “Cop City.” (Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

Priscilla Grim lay comfortably in her hammock reading and enjoying the thick foliage of the South River Forest as music blared a few dozen yards away. Once the sun had set, she began making her way over to the South River Music Festival. But as she walked through the forest, police came at her quickly and without identifying themselves.

There was a flash of lights, the sound of heavily armed men running towards her, and a burst of screams. Then she was being dragged through the darkness.

“I thought I was going to lose my life,” she recalled.

Police carried her to a nearby parking lot where they were corralling the other people arrested during a multi-agency raid on the forest. The detainees were separated into two groups: out-of-towners and locals. Grim, the out-of-towners, and a few locals were sent to DeKalb County Jail. When she asked what she was being charged with, an agent with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) told her that she and the others would find out later.

It wasn’t until she was processed that Grim learned she was being charged with domestic terrorism.

“I knew that they were charging people with domestic terrorism. I knew that that was a risk, but I was literally just reading books in the forest, so it was really shocking,” Grim, a Nuyorican activist and digital marketing strategist, told Latino Rebels.

Twenty-two others of the 35 people arrested during the raid on March 5 were charged with domestic terrorism. Following her violent arrest, Grim spent “31 days in DeKalb County hell,” where she says she saw inmates severely mistreated and forced to live in miserable conditions, even threatened by staff.

The March 5th arrests came after a separate group of more than 150 or so activists in black bloc attacked a construction site and police infrastructure about three-quarters of a mile away. So far, none of the arrestees have been linked to specific actions, and many believe the multi-agency raid on the festival was the police’s “revenge.”

To date, 42 activists have been charged with domestic terrorism under a rarely-used Georgia statute for their affiliation with the Stop Cop City and Defend the Atlanta Forest movements, which aim to prevent the destruction of 85 acres of forest to build the $90 million Atlanta Public Safety Training Center —known as “Cop City“— in a majority Black community in unincorporated DeKalb County, bordering the City of Atlanta. Each of the charged faces between five and 35 years in prison, although the warrants for their arrests do not accuse them of hurting anyone or vandalizing anything. Some warrants merely cite that the accused had mud on their clothes.

While Georgia law enforcement has repeatedly claimed that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has classified the Stop Cop City and the Defend the Atlanta Forest movements as “domestic violent extremists,” DHS denies classifying any specific group as such. However, DHS does use the term in referring to individuals “who seek to further social or political goals, wholly or in part, through unlawful acts of force or violence.”

An activist holds a sign that reads “Forest defenders not domestic terrorists” at a rally at DeKalb County headquarters during the Stop Cop City movement’s sixth week of action in late June. (Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

Attempting to justify the charges against the activists, Nelly Miles, director of the GBI’s Office of Public and Governmental Affairs said: “Although DHS reports that they do not classify or designate any groups as domestic violent extremists, the description provided by DHS for a domestic violent extremist does in fact describe the behavior of the individuals of the group in question which is being investigated by the GBI multi-agency task force.”

“This law should not be on the books —let’s make sure that it’s said without question— for the reasons that it’s being used right now,” said Chris Bruce, policy director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia. He remembers speaking at hearings and challenging state legislators when the domestic terrorism law was being expanded to include property crimes in 2017, knowing that it would likely be used to target protesters.

While proponents of Cop City say the facility is necessary to train police and fire services, opponents say it will only be used to further militarize police against social movements, as has been evident by the repression against the Stop Cop City movement so far.

“A lot of times protestors are protesting and exercising their constitutional rights. When the government does not agree with it, they’re trying anything and everything they can do to intimidate individuals,” Bruce said.

However, police repression did not start or end with the raid on the music festival.

In addition to the 42 charged with domestic terrorism, three activists with the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, which helps pay bail for protesters and find them lawyers, were arrested on racketeering charges. Three activists are facing felony charges for handing out flyers.

On January 18, during a multi-agency raid on the forest, Venezuelan and Indigenous eco-activist Manuel “Tortuguita” Esteban Paez Terán was killed while sitting cross-legged with their hands up, according to an independent autopsy requested by their family. Police originally said Tortuguita had fired at them first, but body camera footage appears to point to friendly fire. A report by the DeKalb County Medical Examiner’s Office found that Tortuguita had no gunpowder residue on their hands and declared the death a homicide.

After their death, Tortuguita quickly became the movement’s martyr and galvanized the fight the Stop Cop City and Defend the Atlanta Forest movements, turning what was originally just a local struggle into a flashpoint for American politics and an international fight for police abolition. For Latinx activists whose family histories are marked by U.S. imperialism, it’s a stark reminder of how the imperial boomerang will eventually come back home.

The Imperial Boomerang

While there is some debate as to whether Tortuguita was the first land defender killed by authorities in the United States in recent decades, their murder was still “unprecedented.” Many point to it as a “chilling evolution” of the way that eco-activists throughout Latin America have lost their lives while fighting to protect the environment.

More than 1,700 eco-activists were killed over the last decade while “trying to protect their land and resources,” according to Global Witness. Over 75 percent of the killings occurred in Latin America, with Brazil and Colombia being the most dangerous countries for environmentalists.

The criminalization of environmental activism has been a widespread strategy across the region. “The most obvious form of criminalization is enforcement of criminal penalties for actions that at most warrant administrative sanction,” Moira Birss wrote in a 2017 issue of the NACLA Report on the Americas, in which she explains that limits and restrictions on protest can also be part of the strategy, including arbitrary detention, unduly elevated charges, lack of due process, and stigmatization by public officials—all of which have been deployed against the Stop Cop City movement.

After the Atlanta Solidarity Fund was raided on May 31 and three of its members charged with racketeering, Bruce remembers worrying that the ACLU would be hit with similar charges for its continued defense of the Cop City movement. He explained such police tactics as a dangerous escalation that attempts to usurp the constitutional right to bail that deviates from the original intention of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act: going after gangs and other criminal enterprises.

Sheriff’s deputies prepare flexicuffs in case they need to quickly apprehend activists during a protest at Fulton County Jail during the Stop Cop City movement’s sixth week of action in late June, Atlanta, Georgia. (Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

Palta, a Chilean activist who immigrated to the U.S. as a child, stood only some feet away from the violent arrest of Victor Puertas, an Indigenous immigrant activist, during the March 5th raid. Palta remembers being horrified by the way police tased Puertas and choked them before dragging them away—likely to the same group Grim was taken to.

Puertas is the only person charged with domestic terrorism who remains incarcerated, since Georgia law states that any domestic terrorism charge must be tied to an underlying felony and the felony jeopardized his immigration status. After being held without bond for the 90-day legal maximum, Puertas was immediately transported to Stewart Detention Center, notorious for its poor conditions, by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). While they remain there to this day, Puertas has not been criminally indicted and the court has presented no evidence against them, their lawyer told NowThisNews.

Although officials have not publicly stated whether ICE will use Cop City to train its agents, Palta believes its facilities will inevitably be used to teach ICE and other agencies to target immigrants. And with the possibility of being charged with a felony for merely innocuous things —like attending a music festival— jeopardizing their immigration status, Palta fears it will push immigrants further into the margins of society.

ICE did not respond to Latino Rebels’ request for comment.

Although local opposition to Cop City abounds, Georgia officials have continually pointed towards “outside agitators” as the ones inciting direct action against the planned police facility. The trope has long been a staple used against social change protests, particularly throughout the civil rights movement.

For Latinx activists, however, the “outside agitator” narrative holds double meaning, as many of them or their families were forced out of places in Latin America due to U.S. imperialism. The outside agitator narrative serves to protect imperialism and settler colonialism, explained Grim, who was raised in Georgia. Her family left Puerto Rico “to escape colonialist violence at the hands of the United States,” she wrote in a May essay for Scalawag.

“If we are going to move past the system that’s in front of us right now, we all have to work together. All of our grievances are connected at the end and this is certainly as true in Puerto Rico as it is in Atlanta,” she told Latino Rebels.

Meanwhile, the Atlanta Police Foundation (APF), a multi-million-dollar nonprofit that funnels money into the Atlanta Police Department and owns the lease for the land where Cop City is to be built— has said it plans to recruit 43 percent of Cop City trainees from outside Georgia.

Georgia’s Role as Imperial Training Ground

The United States has often used Latin America, dubbed the “empire’s workshop” by historian Greg Grandin, to test out new weapons and strategies—particularly in the 20th century.

Georgia itself has a strong link to the criminalization of Latin Americans and the ensuing spread of violence across the region. Since 1984 it has been home to the School of the Americas (SOA), now called the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC). Best known for its connection to various U.S.-backed military dictatorships throughout Latin America, its alumni include “dictators, death squad operatives, and assassins,” as Vanderbilt professor Lesley Gill wrote in his 2004 history, many of whom have committed a long list of human rights abuses and crimes against humanity.

The facility also played a significant role in exporting policing techniques and strategies to Latin America.

“American interference has ruined my family,” Palta said, explaining how their family lived through the U.S.-backed Pinochet dictatorship in Chile and moved to the U.S. in the early aughts hoping for a better life.

Although Gen. Augusto Pinochet did not attend the SOA, he was held in high esteem by it and the U.S. government. A ceremonial sword he gifted the school hung in the commandant’s office until the early nineties, and multiple SOA alums ran concentration camps in Chile and participated in the so-called “Caravan of Death,” a Chilean Army death squad.

“I was once told that fascism is imperialism turned in on itself, that fascism is the domestic form of imperialism, and that helped me put into perspective what the implication of Cop City is,” said Christine Stonebraker-Martinez, co-director the InterReligious Task Force on Central America and Colombia, a Cleveland-based peace and human rights group that has campaigned to close WHINSEC for years.

While officials have not made any public links between WHINSEC and Cop City, Stonebraker-Martinez fears that Cop City could eventually play host to similar programs as the military school. They point specifically to the Georgia International Law Enforcement Exchange, which arranges for Georgia law enforcement to train with other government security forces. The controversial exchange between Georgia law enforcement and the Israeli Defense Force is often called the “deadly exchange” by critics.

WHINSEC did not respond to Latino Rebels’ request for comment.

Chrissy Stonebraker-Martinez, co-director of the InterReligious Task Force on Central America and Colombia, speaks at a faith coalition rally for Victor Puertas held outside the Stewart Detention Center in Georgia during the Stop Cop City movement’s sixth week of action in late June. (Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

Latino Rebels spoke with multiple Latinx land defenders who echoed Stonebraker-Martinez’s concern that officers trained at Cop City would look and emulate the ways in which police departments and militaries repress social movements in other countries. Part of the worry comes from seeing how weapons and technology originally deployed abroad by the military are now used by police departments through the 1033 program, a Department of Defense program that transfers surplus equipment from the U.S. Armed Forces to civilian law enforcement agencies. While hardware has passed hands between foreign and domestic security forces, police have also used military tactics to an increasing degree, as seen throughout the 2020 George Floyd protests.

“The federal government is desperate to quell civil unrest. We see how that has been handled overseas. No mystery on how it will happen here,” said Cassian, a Latinx forest defender.

Seeing more military strategy and hardware mixed with an urban warfare training center in their city, many activists can’t help feeling that police are preparing for war at home.

“I didn’t sign up for a war, but I felt like I was drafted into one because I had two dozen SWAT with long rifles pointed at my head at 7:30 in the morning,” Stonebraker-Martinez said, referring to a police raid on the Lakewood Environmental Arts Foundation on March 11 of this year.

Only one person was arrested during the raid for a traffic ticket in a neighboring county. Activists found their tents and supplies destroyed as well as multiple vehicles with their windows smashed when they came back.

A Tired Community Continues Forward

For Palta, simply being Latine has been a “specter that weighs on (their) mind” since Tortuguita was killed earlier this year. Even though their parents have green cards, they worry about what could happen if their involvement in the movement became widely known.

Palta remembers a sign in the forest that read “You are now leaving the USA” and feeling like they had “politically” left the country once they had walked past it. To them, being in the South River Forest with other forest defenders was the first time they felt truly accepted.

The forest has been closed since the March raid and no official date has been given for reopening. Now, forest defenders face the challenge of organizing in the city, where police have more resources and know the terrain.

Building community has been an integral part of keeping the Stop Cop City and Defend the Atlanta Forest movements together through everything they have endured. Activists attribute the resilience of the movements against the continued police repression to the strong connections their members have established with each other.

“Atlanta is a special place. Even as I was getting arrested, I knew that everyone had my back, that I would not be left behind or forgotten because I had experienced the solidarity of this movement already,” Puertas said in a letter dictated to Rev. Nolan Huber-Rhoades and read aloud by Huber-Rhoades during a faith coalition visit to Stewart Detention Center during the movements’ sixth week of action in late June.

The activists saw a big win when a federal judge granted a 60-day extension for a referendum effort to put the land lease to the Atlanta Police Foundation on the ballot. The City of Atlanta is currently appealing the judge’s decision.

In court filings the City of Atlanta attorneys had previously said the effort was “futile,” with Mayor Andre Dickens saying it would be “unsuccessful, if it’s done honestly.”

Activists confront police at a rally outside Cadence Bank in Atlanta, Georiga, which is providing the Atlanta Police Foundation with a construction loan. (Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

As far as those charged with domestic terrorism, things are looking up. Defendants have not been indicted, and DeKalb County District Attorney Sherry Boston recused herself from the prosecution, telling WABE-FM that “it is clear to both myself and the attorney general that we have fundamentally different prosecution philosophies.”

While a lot of the movement’s energy is focused on the referendum, that has not stopped its members from continuing to engage in direct action.

During the sixth week of action, multiple Atlanta Police Department motorcycles were torched and several cars had their windows smashed. Across the United States, land defenders have also engaged in solidarity actions and targeted harassment of the companies involved in funding and building Cop City, including UPS, Bank of America, and Brent Scarborough. Multiple sponsors and contractors associated with Cop City have dropped out of the project, including Reeves Young Construction, Quality Glass Company, and most recently Atlas Technical Consultants.

“If you build it, we will burn it,” forest defenders have vowed countless times.

The Stop Cop City and Defend the Atlanta Forest movements have remained resilient against police repression, springing back and receiving even more attention after every confrontation. Even though they no longer have the South River Forest as a staging location, forest defenders promise to continue fighting against the construction of Cop City on multiple fronts. Many believe that if the movement is victorious, it will serve as a springboard for similar movements across the world, which are fighting their own battles against authoritarianism and environmental destruction.

“We’ve fought for too long, we’ve struggled so much, for this to just be about Cop City,” said Palta.

***

Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco is the Caribbean correspondent for Latino Rebels, based in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Twitter: @Vaquero2XL