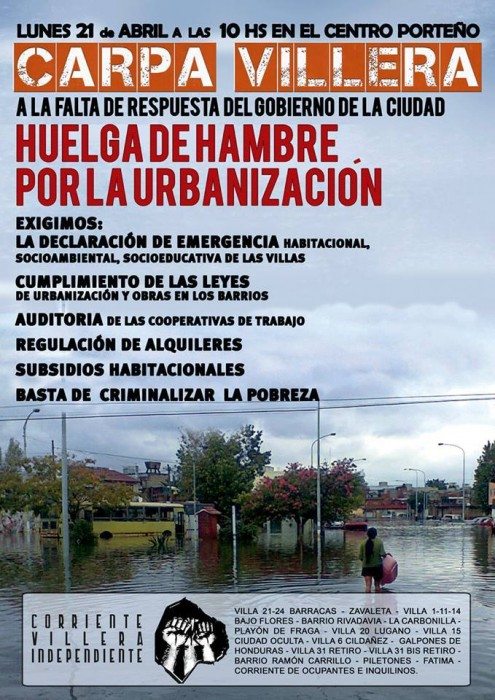

BUENOS AIRES—Neighbors and activists from Buenos Aires’ poorest villas (neighborhoods) began a hunger strike Monday in a giant tent situated around the city’s obelisk at the intersection of two main avenues. The organizing group, la Corriente Villera Independiente (CVI), is demanding their neighborhoods be urbanized by the city government.

A declaration by the CVI states, “A villera tent for the city government’s failure to respond. Hunger strike for urbanization. We demand: the declaration of a housing, socio-environmental and socio-educative emergency in the villas, enforcement of the urbanization laws and construction in the neighborhoods, authorization for work cooperatives, rent regulations, housing subsidies. No more crime against the poor.” (Villero/a is a loaded slang term used to describe anything that has to do with the poor neighborhoods.)

The group began to set up the tent at 10 a.m. Monday morning. Villa 31 resident Dora Mackoviak told Periódico VAS that the group thought they would have to confront the police, who ultimately remained silent and still.

“This is the peaceful way: a hunger strike that represents the 17 villas of Buenos Aires, to demand that the city government meet the urbanization law of our neighborhoods,” Mackoviak said.

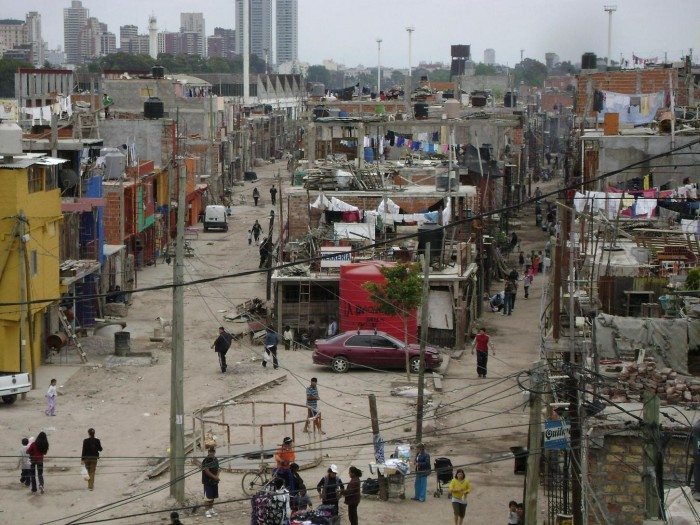

A Tale of Two Cities

Buenos Aires is truly two different cities. Buenos Aires’ largest villa, the Villa 31, is located just blocks from the city’s fanciest hotels, the Four Seasons and the Plaza Alvear. All that divides these two cities are train tracks. Villas first appeared in Buenos Aires and other major Argentine cities during the 1930s economic crisis when migrants came to urban areas in search of work.

In a Monday press conference, CVI shared its reasons for the hunger strike: “Given the two-city model promoted by Mauricio Macri (Buenos Aires City Governor) where the rich city excludes the poor, the lack of will to solve this housing problem is evident.”

Rafael Klejzer, one of the CVI’s representatives, was the one who formalized the strike. “We are tired of visiting offices, ministries and secretaries. The history of CVI is written in the street, in every block and walkway of our neighborhoods. It is a current that was born among the repression against the American Indian and the lack of response to the housing crisis in Buenos Aires,” he said. Behind him is the CVI’s banner featuring the faces of Che Guevara and Padre Carlos Mugica (a villero priest who was murdered for his activism against inequality in 1974).

“After so much struggle and waiting in vain, we decided to start this hunger strike with a list of demands having to do with the creation of a city Ministry of Housing that would eliminate villas and the housing crisis altogether,” Klejzer said. Activists and neighbors stressed another demand: the authorization to work in individual, neighborhood co-ops.

To close, Klejzer asked for an end to the criminalization of the poor. “If you want drugs, go to Puerto Madero and the gated neighborhoods of Tigre (wealthy areas in Buenos Aires): that’s where narcotraffic is generated in Argentina. Just because we are poor workers does not mean we are criminals. It hurts every one of us that our children are stopped and questioned when they leave their neighborhoods.”

Neighbors will rotate through the hunger strike every five days. The strike will be indefinite until city officials respond to what the CVI has proposed. The organization has planned activities for the week including open radio, panels, talks, cinema debate and live music.

“Why are we doing this?” Klejzer asked, “Because we are sure that Macri’s (city) government will let us die here.”

Support for the Cause

Luis Zamora, lawyer and representative of the Autodeterminación y Libertad (Self-Determination and Liberty), political party, is one of the CVI’s biggest supporters. “I support them and fully agree with their demands,” he told independent media, lavaca. “They are bringing Argentina’s biggest drama to the surface: housing. It is a dramatic problem and it is important that they [strike] at the center of the city.”

Zamora focused on the use of the city’s budget. “Housing rights should be taken care of by the budget to guarantee that everyone has a roof,” he said. “But they are in campaign mode. Macri is not worried about how to urbanize the villas, he is worried about how to become president.”

La Garganta Poderosa, a villera work cooperative, said it is also supporting the hunger strike. “We fully support this initiative from the 15 assemblies that are part of La Poderosa and La Garganta as a villera work cooperative. We give them all the tools we have to bring our historically neglected neighborhoods’ claims to the table. They have shown that they have tried communicating by all means possible, shouting from the villas for true emergency and urgency to resolve the housing crisis and regulate the working conditions in our neighborhoods.”

Enough is Enough

Leo, a resident of the Villa 31 and CVI activist, said: “They are treating us as if we don’t exist. They always say they are going to do something, but it’s a lie. Enough with the lies. Living in the trash disgusts us and that’s why we’ve come to this decision. We are sick of the construction work they never do, of the flooding, of the meter of water in the houses and of the sick kids. Housing is the most urgent. The villas have had enough.”

The 1998 law that established urbanization of the villas was never realized. In 2009, a law was passed guaranteeing urbanization of Villa 31 including paved streets, electricity, gas and new schools. It has yet to be fulfilled.

***

Taylor Dolven is an “infinitely curious journalist” based in Argentina. You can follow her on Twitter @taydolven. She is part of a growing independent media movement in Argentina, miarevista.com.

The anti-religious but, http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html above all, anti-Christian efforts which distinguish the present epoch have a character of concentration and universality which marks the stamp of the Jew, the supreme patron of the unification of peoples, because he is the cosmopolitan people par http://www.cintaberita.com excellence; because http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html the Jew prepares by license of the libre-pensÇe, the era called by him ‘Messianic’ – the day of his universal triumph. He attributes its near realization to the http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html principles spread by the philosophers http://www.cintaberita.com of the eighteenth century; the men at once unbelievers and cabalists, whose “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html work prepared the Judaising of the world. The character of universality will be noted in L’Alliance-isrÇlite-universelle, in the Universal Association of Freemasonry, and in the more recent auxiliaries, L’Alliance-universelle-religieuse, http://dokterpoker.orgopen to those who are still frightened off by the name of Israelite and finally in the Ligue-universelle de l’enseignement.