Editor’s Note: A previous version of this piece was published on Dr. Rodríguez’s blog.

Nate Cohn in The New York Times opened a racial pandora’s box with his article on the whitening of Latinos. He received responses from a number of interested observers of Latino issues—from Latino Rebels to academics such as Amitai Etzioni and Manuel Pastor. Today Cohn retorted with another article in which (kicking and screaming) he insisted he was right. Unfortunately, the study which was the stage for this still debate has not been released. One proposed nuanced, preliminary understanding of the study by D’Vera Cohn of the Pew Research Center was lost in the initial barrage of articles.

When an issue —usually the province of nerdy academics writing for peer-reviewed journals not read by the public— releases this much energy, it is because Nate Cohn hit a raw nerve at the core of decades of debate within and without the Latino community about Latino inclusion.

This debate, which began immediately after the end of the Mexican American War in 1846, was initially fought through isolated acts of armed insurrection, through the legal and illegal expropriation of Mexican land grants held by wealthy Mexican, Hispano landowners (including the intermarriage with Anglos, which had the same outcomes). In the end, and some argue that by the 1880s in California, Mexicans had been neatly positioned in a fuzzy category at the bottom of the United States’ racial hierarchy but still somewhat in a higher rung than African Americans. Later, as the Mexican community had changed with immigration from Mexico, many of whom were recruited by U.S. corporations in mining and agriculture, the struggle took another political character as an insider group. Then the strategies were labor/trade union struggles and other activities to gain civil and human rights.

Ironically, after all these years, Latinos are, as a group (an important distinction) still in the same spot. Recent data on home ownership, academic achievement, school expulsions, children in foster care, racial profiling have African Americans in the bottom experiencing the most intense discrimination and Latinos somewhere in the middle between whites and some Asians groups.

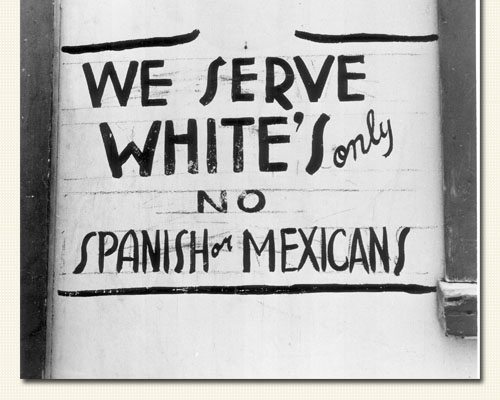

Because of this intermediate position in the racial hierarchy, for years, especially during the 20thcentury, the first major Latino (mostly Mexican) advocacy organizations, like the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), rather than joining with African Americans in challenging the entire racial structure chose to try to collectively wiggle their way into whiteness. One individual informal way of doing this was by identifying as “Spanish” rather than Mexican, which was a strongly racialized term.

Mexican American novelist Américo Paredes wrote in his novel George Washington Gomez than in Texas there were wealthy and poor blacks, but only wealthy Spanish and poor Mexicans. Class has always had a pivotal role in racial and ethnic identification among Latinos. For other Latinos —like Puerto Ricans in the Northeast— the strategy was not that overt. It was more subtle through the self-identification as “Spanish” to establish a difference from African Americans. Cubans on the other hand strongly identified as not-black given their social context in the Florida Deep South. The organization Marti-Maceo, founded in 1899 on José Martí’s anti-racist values eventually became segregated in 1900.

One aspect of the process of the incorporation or not of Latinos into the mainstream of the United States (white middle class) is the need to differentiate between individual racial/class mobility and collective. It is obvious that some individual lighter skin Latinos have crossed over into whiteness (some have returned, depending on whether it was strategically advantageous to be Latino). The focus, it seems to me, is what is happening to Latinos/Hispanics as a collective?

Historically, the “white” strategy has backfired, one not very well-known historical event is the Hernandez v. Texas case decided by the Supreme Court. Since Mexicans were legally considered white (not socially), Mr. Hernandez was accused of murder and was judged by a jury of his peers. Since Mexicans were legally white, his jury was entirely white. In fact, in Jackson County where the trail was held, not one Mexican American served in a jury in 25 years. Mexican American lead attorney Gus Garcia was able to get the Earl Warren Court to unanimously agree that the 14th Amendment protected other classes beyond the black/white binary. Being formally white did not entail the privileges whiteness entails to individuals in the United States.

The reality is that many individual Latinos have traversed the whiteness border depending on their class, education and color. In “Shades of Belonging” (2004), Sonya Tafoya found that self-identification as white is influenced by whether the person is foreign born (more likely to choose “other” in 2000 census), or native born. Being a citizen, native born with higher education increases the probability of individuals choosing white. As this study and others have found, they are also more likely to vote for the Republican Party. Does this mean they are living a “white” life or are they aspiring to truly be “white?”

It seems obvious that skin color may be a factor on whether people identify as white, as Tanya Bolash-Goza in her “Dropping the Hyphen? Becoming Latino (a)-American through Racialized Assimilation” (2006) shows that experiencing discrimination leads Latino to be less likely to identify as “Americans” (code for “white”) and more likely to self-identify with a hyphen as Mexican-American. So the color of a person’s skin will still be a factor in how society incorporates or not individuals and groups into the middle class white fold. In their 2010 study “Latino Immigrants and the U.S. Racial Order: How and Where Do They Fit In?,” Reanner, Frank et. al. state:

Some Latinos will be successful in the bid to be accepted as ‘white’ – usually those with lighter skin. But for those with darker skin and those who are more integrated into U.S. society, we believe there will be a new Latino racial boundary forming around them.” So in their view skin color and the length of experience with the system of race (native born versus foreign born) will determine their sense of membership in racial categories.

But the recent study by Laura Pulido and Manuel Pastor, “Where in the World Is Juan—and What Color Is He? The Geography of Latina/o Racial Identity in Southern California,” adds another dimension that is crucial. First, they find again that the longer Latinos experience the racial system, the clearer it is to them that they will not be part of the most favored status.” But another novel contribution is space—space does matter. As geographers they have reminded us that we develop a social identity in the context of community and that segregation is a power force in shaping the dynamics of the social construction of identity. The more time we spend interacting with others in similar conditions to us, the more similar we become. These are conditions that lead to identifying as “Some other Race. (SOR):”

Latinas/os living in area that have a higher percentage of people of color and are more racially segregated are more likely to identify as SOR, while those living in the most suburbanized areas are much more likely to identify as “white.” If these are the factor on which the social construction of a racialized identity are hinged, there will be no “whitening” in a massive scale anytime soon. That would entail a radical transformation of U.S. society and an incredible process of upward social mobility for Latinos.

Another possibility which is mostly discounted by Pulido and Pastor is the Bonilla-Silva thesis of a new reconfiguration of our racial architecture away from the binary system that now prevails (from “From Bi-racial to Tri-racial: Towards a New System of Racial Stratification” in the USA.”) Bonilla-Silva argues that what might happen, and the data on segregation could support this, is a tri-racial system with whites at the top, Latinos as a “buffer” between whites and African Americans at the bottom. This buffer would be made up of Latinos who could “pass” as whites while darker skinned Latinos would join the lower stage with African Americans. This also depends on a robust process of upward mobility for Latinos which remains to be seen.

This debate has usually had Mexican Americans as a core centerpiece of what this country portends for Latinos. Being the largest Latino group and the one who has had the longest experience in this country, it is reasonable for their experience to be instructive and determinative for the entire Latino experience. This is the reason why some moderate and conservatives have focused on Chicanos and have argued that Mexicans will be fully incorporated. One classic version of this thesis is Peter Skerry, whose bookMexican Americans: The Ambivalent Minority in 1993 also caused a roar when he said that Chicanos were on the same assimilation path of European Americans. His title was in some sense interpreted as a backhanded attack at Chicano activists by implying that Mexican Americans wanted to assimilate, a process challenged by many Chicanistas. Time proved him wrong, since in 2014 we are still debating the process of the full incorporation of Latinos.

In the end Mr. Cohn cites professor Sanchez from Latino Decisions: “Gabriel Sanchez, an associate professor at the University of New Mexico and a director of research for the polling group Latino Decisions, interpreted the upward swing in white identification as consistent with the possibility that well-assimilated Hispanics might become “for most social purposes, white.” Professor Sanchez is right. However, that was not the issue—of course assimilated Latinos will identify as “white.” The issue is how broad the process of whitening is? Will it encompass a large proportion of Latinos? Will it continue to be a minority experience among Latinos?

My perspective, unless there is a radical transformation of U.S. society and economy: it will be a minority experience for Latinos.

This not an abstract issue since a transformation like this will change the nature of politics in the United States. “White” Latinos are more likely to vote for the Republican Party and support conservative causes (with some exceptions). As Garcia-Bedolla showed in “The Identity Paradox: Latino Language, Politics and Selective Dissociation” (2003), assimilation tends to divide the community and disempower Latinos. This study shows how more assimilated Latinos were more likely to vote in favor of Proposition 187 and distance themselves from Latino immigrants. This proposition would have expelled undocumented children from school and deny health care among other public services. Fortunately, the California Supreme Court found it unconstitutional on two grounds, violation of 14th Amendment (due process) and a violation of the supremacy clause that establishes the federal government’s primacy over immigration issues.

***

Victor M. Rodriguez is a Professor at California State University, Long Beach and author of Latino Politics in the United States: Race, Ethnicity, Class and Gender in the Mexican American and Puerto Rican Experience in the United States. (Book link here.) You can follow Dr. Rodriguez @rodrigvm.

There’s a book on this nonsense? Lol

I really liked your article , your article is very petrified me in the learning process and provide additional knowledge to me , maybe I can learn more from you , I will wait for your next article article , thanks

http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan

http://yakuza4d.com

http://yakuza4d.com/home

http://yakuza4d.com/daftar

http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main

http://yakuza4d.com/hasil

http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi

http://beritamedannews.blogspot.com

http://www.cintaberita.com

http://yakuza4d2.com

http://yakuza4d2.com/promo

http://yakuza4d2.com/daftar

http://yakuza4d2.com/cara_main

http://yakuza4d2.com/hasil

http://yakuza4d2.com/buku_mimpi