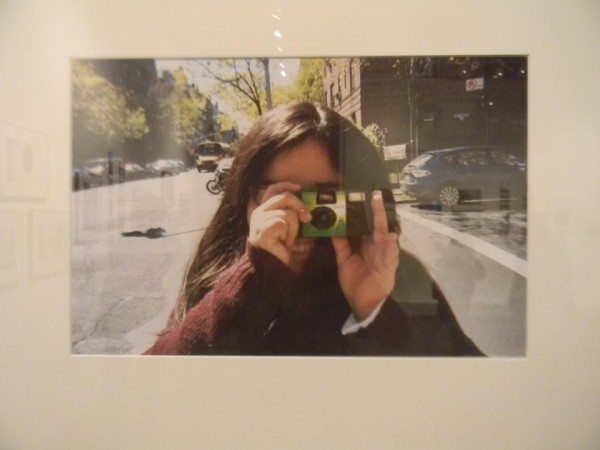

Being a single mother is a challenge. Immigrant mothers face those challenges every day, and they also have extra hurdles to jump. To document these aspects of their lives, an inter-generational photography workshop organized by Mano a Mano, NYC (Mexican Culture without Borders) gave cameras to immigrant parents and their children born in the United States.

Last Saturday, at The Grady Alexis Gallery in Harlem, Luz Aguirre who grew up in Mexico was there with her daughter Eve, who grew up in NYC.

“As a single parent, you know everything about your kid, but you forget to tell them about yourself,” said Aguirre.

The project also allowed mother and daughter to further bond. Running her household and holding a full-time job, Aguirre told me how stressful it gets, and how little time there is to actually share memories and interests on a daily basis:

As we were taking pictures and displaying them, I was able to tell Eve about my own interests; my love for writing in Spanish, for example. Sometimes you get home and it’s all about your kid, you forget yourself completely. But there were things I got to share with her about myself.

Aguirre feels very close to her daughter, she speaks to her in Spanish, but her daughter mostly answers in English. What Aguirre found interesting about the project were the differences in perspectives between herself and her daughter:

For the project we had to photograph a theme about our idea of Mexico and America. When looking at the final images, we saw how my idea of Mexico and her idea of Mexico were completely different.

The exhibition was presented as the product of an Inter-Generational Photography workshop led by Rafael Gamo Fassi and Susana Arellano Alvarado. The project began with an interest for documenting the cultural differences.

“We planned the class after we heard, from a conversation, that one of the biggest problems in the Mexican community is the cultural clash; parents born in Mexico and their children born in the United States” said Gamo Fassi, an architect and photographer.

As the class developed, the visions of parents and those of their children, captured in images, revealed their different perspectives, but it also brought them together.

“We asked parents and children to photograph the same subjects, and at the end of the class, parents and children presented their photography. We recorded their dialogues. Children got to hear stories about how their parents came to the United States, and how their lives were in Mexico,” explained Arellano Alvarado, who also implemented this project with children and parents in different parts of India.

Rosali Arteaga wants to be a doctor when she grows up, and participated in the project with her mother, Martha Ponce. Rosali, who enjoyed going out to take pictures with her mother, was raised bilingual:

We speak in English more than in Spanish. But sometimes we use Spanish.

Ponce explained how wonderful it was for her to share time with her daughter through this project:

I learned that you need to make friends with time. This project gave us an advantage because we were able to share experiences. I invite parents to be a part of their children’s lives, because that’s the key to their success.

The exhibit also included a poetry reading by NYC’s only creative writing group led entirely in Spanish. “Los Lunes,” named after the day the group gets together, is a bilingual group with writers coming from every part of Latin America. Daisy Flores, a member of the writing group who was also raised by Mexican immigrant parents, read her piece titled “The Unspoken:”

I don’t know what it is, but it’s difficult to look at you in the eyes or even your face when I’m in the same elevator as you or when I see you riding your bike with your 10 deliveries or when you pour water on my glass or pick-up my dirty plate. I feel as if I have to pretend I don’t know, as if I’m blind and dumb. A spectacle for you and myself because I lie. And it’s a mixture of ache and helplessness on my part. Because I do know. I know first hand that I need you to be where you are with your long hours, unfair pay, solitude, and sacrifice to be in my cubicle typing away my stupid memos.

That’ s what it takes to help out your wife who cleans, babysits, and cooks for a family that is not her own so your kids can have new clothes for school and fit in, on the surface anyways. Because they too see and play dumb. They look every day and see you come home tired to drink a cerveza and forget your day in the blue light of the TV. When you can’t help with their tareas, when they have to translate for you. They know. Your hijos look at this and they will want more, not sure what more, but definitely not this. They will ache too but continue on as best as they can, go to school, graduate, travel forget a little of what they’ve seen so that when they are on the elevator, street, and restaurant they will not look but they will know the fate they escaped

Flores’ poem is a reminder and a written portrait of those considered first generation immigrants who remain invisible in NYC. They are servers, delivery boys, construction workers, housekeepers. They are mothers and fathers of children who speak English, and raise their kids through their less-visible labor, providing their kids with opportunities they never had; such as attending college or learning english. The exhibit shows how these socio-economic and generational differences are present. As children of immigrants grow, adapt, and face new challenges, this exhibit allows two generations to stop, capture moments, and tell their stories through photography.

***

Carolina Drake is a writer and reporter based in Brooklyn, originally from Argentina. She writes about Latin America and NYC. Follow her @CarolinaADrake.

[…] Mexico to NYC: Through Photography, Immigrant Single Moms and Children Share Stories […]