On Monday Iowa Rep. Steve King was caught off guard when DREAMer activists Erika Andiola and Cesar Vargas confronted him about his opposition to President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy, which has allowed Andiola and hundreds of thousands of others to avoid deportation, get a driver’s license and find work.

The seven-minute video offers a fascinating glimpse at the debate concerning flaws in current immigration law. While Andiola and Vargas attempt to argue from a moral standpoint, Rep. King keeps reverting back to “the rule of law.”

This introduces the question as to whether undocumented immigrants act immorally by living in the United States without government permission.

But before I talk about morality and immigration law, let me share some thoughts.

First, undocumented immigrants are in the United States illegally. No matter how or why they’re here, if their being here is not permitted by law, then, by definition, they are here illegally. After all, driving through a red light is not permitted by law, and to do so would would be illegal. (Note: This is very different than saying undocumented immigrants are illegal themselves, which would be nonsensical.)

Second, by instituting policies like Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which exempts unlawful residents of the United States from lawful removal, President Obama shirks one of his greatest constitutional duties—to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.”

Because immigration law is a civil issue and not a criminal one, I suppose a proper analogy here would be that of a judge who allows someone to break a legally binding contract (and then allows that person to enter into an illegal contract, if they work in the United States).

Rep. Steve King was right when he told DREAMers Erika Andiola and Cesar Vargas that there is something known as “the rule of law.”

Yet the rule of law is not written in stone. If American history teaches anything, it’s that the rule of law is malleable and forever changing.

The U.S. Constitution, for instance, required the federal government to pursue runaway slaves and see them returned to their masters. Subsequent slave acts made it illegal for anyone —citizens, police officers or elected official— to keep fugitive slaves from their lawful masters. Children born to runaway slaves were also deemed slaves themselves and the property of their mothers’ masters, for life.

The 18th Amendment made the formerly legal act of drinking beer illegal in 1920. By 1933 the 21st Amendment had made drinking beer legal again.

The Supreme Court deemed segregation constitutional in the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896, but less than 60 years later the Supreme Court deemed “separate but equal” unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education.

Interracial marriage was punishable by prison time throughout the South until the Supreme Court ruled as unconstitutional any race-based restrictions on marriage in 1967.

So why is that a nation of laws has seen its laws change constantly over so brief a lifespan?

It’s because, as Aviva Chomsky writes in Undocumented: How Immigration Became Illegal, “laws only exist in social context. … The law is never neutral, but rather reflects power relationships in society.”

According to Chomsky, Latinos have been criminalized through the immigration system for the same reasons that blacks have been criminalized through the justice system—to preserve the caste system outlawed by the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

Still, on a more basic level, it’s easy to see why laws change so much. Human beings are imperfect, leading them to form imperfect societies governed by imperfect laws. Incidentally, the founders of this nation echoed the same sentiment when they sought “to form a more perfect union” and provided a means of amending an imperfect document. And since the early years of the republic, it has been regularly necessary to improve the Constitution and ignore faulty laws in order to move toward the more perfect union that the founders vaguely imagined.

In that sense, the Constitution is a living document, ever evolving as American society evolves.

Dr. Martin Luther King famously distinguished the difference between laws as so:

There are two types of laws: just and unjust. … One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that ‘an unjust law is no law at all.’

This is the moral ground all DREAMers stand on. And this is the moral authority President Obama must call on when he seeks to improve the lives of undocumented immigrants outside of Congressional approval.

Yes, immigration law is the law of the land. But it is also unjust, and so long as it is, undocumented immigrants are not obliged to obey it.

Current immigration law is unjust because it makes criminals of children either for something they did under their parents’ guidance or on their own. No one who has discussed the byzantine immigration system with an average adult expects someone 17 years of age or younger to fully understand how the law works. So criminalizing a person who comes to the United States as a child, either illegally or by overstaying their visa, is the epitome of immoral.

Such a system brings to mind past laws that allowed for hereditary privileges and enslaved the children of slaves, both of which the United States now claims to be fundamentally opposed to.

The current law is also unjust in that it breaks up the families of citizens and non-citizens alike. In the case of U.S. citizens, citizenship should protect a person from seeing their family members and spouses deported to a foreign country. As for non-citizens, on the other hand, even a common sense of decency should compel government to respect the sanctity of families.

Here, again, even though he was writing about Jim Crow segregation, Dr. King’s words prove pertinent:

Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority. … Hence segregation is not only politically, economically and sociologically unsound, it is morally wrong.

By labeling an immigrant undocumented, immigration law mutilates the humanity of both the immigrant and the nativist, deforming their view of themselves and the other. It causes one side to live in fear while the other side wallows in hatred.

Immigration law also fogs the nation’s understanding of what it means to be a citizen and American by making each designation a mere outcome of birthplace and paperwork, and it prevents otherwise ambitious, hardworking individuals from reaching their full potentials.

What can be more immoral, more unjust, more unnatural to what it means to be an American and, more important, a human being than what I’ve just described?

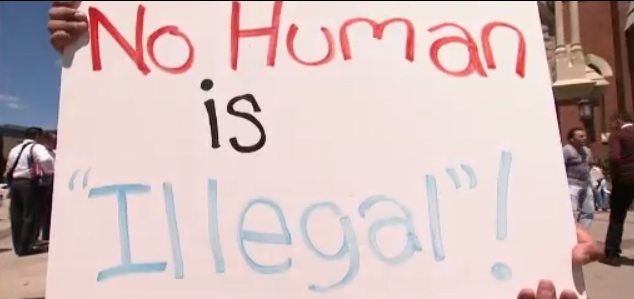

Nativists like Rep. King are wrong to dismiss undocumented immigrants like Andiola and her mother on the simple basis of their unlawful presence in this country. To do so ignores the imperfect nature of laws and their constant state of flux. When someone uses the term “illegal,” he or she forgets that these undocumented immigrants are, after all, actual human beings who deserve the respect, dignity and equal treatment worthy of all people, no matter where they’re born.

“An individual,” wrote Dr. King in 1963, “who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.”

DREAMers and other undocumented members of America’s communities continue leading brave lives of quiet disobedience, whether by confronting hostile congressmen or simply going to work and school.

For his part, President Obama has promised to do what Congress refuses to do by using his executive powers to make the immigration system as fair as any president can without help from the other two branches of government.

Let the cause be well known to all. Let their obstacles be depicted in horrific detail. And let the enemies of justice be identified by name.

Already the moral stench of U.S. immigration law floats heavy over this imperfect land. Soon, hopefully, the American people will become so offended by the rule of law that they’ll opt to change it—yet again.

***

Hector Luis Alamo, Jr. is a Chicago-based writer. You can connect with him @HectorLuisAlamo.