Just when I was getting to like Pope Francis, he shows himself to be a real man of the Church after all. I guess the signs were always there.

Jorge, meek and mild—who washed the feet of convicted female prisoners after becoming the infallible Vicar of Christ—is the same guy who said he wouldn’t consider allowing anyone with a uterus to preach from the pulpit.

The same Frankie from Flores who claimed it wasn’t his place to judge gays and lesbians (those seeking the Lord, of course) is the same man who, as Archbishop Bergoglio, called Argentina’s legalization of same-sex marriage “a scheme to destroy God’s plan.”

Here’s the pontiff who criticized Islamic fundamentalists who use religious doctrine as a basis to commit acts of terror, but then suggested that the staff at Charlie Hebdo brought the recent attack on themselves for insulting the religion of others. He even pretended to punch a papal coordinator who was standing next to His Holiness, saying his strike would only be “natural” had the coordinator said something about the papa’s momma.

I guess no matter how progressive the Pope claims to be—white smoke could emit from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel, whereupon the College Cardinals announce they’ve chosen MSNBC’s Chris Matthews to be the new bishop of Rome—at the end of the day, he’s still head of one of the most reactionary institutions in the history of the mankind. Even as the People’s Pope, Frank’s still a minion of the magisterium.

Now Pope Francis’ decision to canonize Junípero Serra, an 18th-century California missionary, reveals either a loyalty to papal powers that be, a cultural and historical callousness, or both.

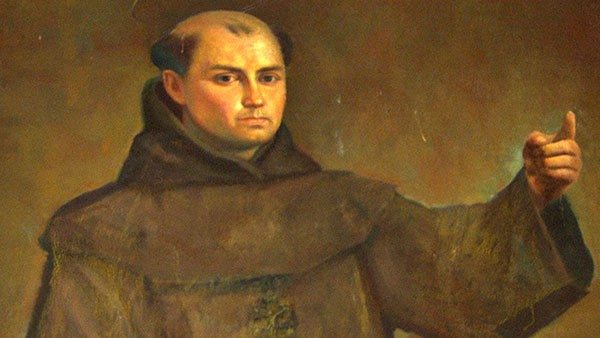

Born on the island of Majorca in 1713 (on my birthday, no less), Serra was one of the most pious members of one of the strictest orders of Franciscans friars, known to mortify his body with whips, burning candles and shirts lined with metal wires pressed against his flesh. Upon arriving in Vera Cruz in 1749, he’s purported to have traveled the 200 miles to Mexico City on foot as affirmation of his unshakable piety—though he would badly injure his leg during the trip and walk with a painful limp for the rest of his life. As “Padre Presidente” of the California missions, Serra was responsible for the sickness, dispossession, torture, enslavement, death and overall misery of hundreds of thousands of indigenous people.

Of course, some people don’t see it that way. For those hoping to gloss over history—especially the bits about how the self-proclaimed civilizers descended on the New World and “behaved like ravening wild beasts,” to quote another famous friar living in another century—Serra can only be viewed as what the Church will soon make him: a saint.

Responding to criticism to Pope John Paul II declaring Serra venerable in 1985, Thaddeus Shubsda, a California bishop, released a report in which five historians claimed they’d encountered no evidence that Serra had treated the natives unkindly. One of the so-called scholars argued that the Franciscan friar had played “a very important role in at least initiating the whole family tradition in California,” while another academic held that, prior to Christendom’s glorious arrival, the benighted tribespeople had possessed “no sense of morality” and “no idea of a social compact.” A third historian speculated that the natives had not yet developed the concept of private property—a common pretext for theft in colonial times—and yet a fourth expert described them as being on the verge of starvation before the Spaniards showed up.

Shubsda’s report has since been further refuted by the real history work of bona fide historians, and based on primary and secondary accounts, we can partly piece together the savage history of colonial California—savagery on the part of the colonizers, mind you.

By Spanish law, missionaries were allowed to treat the newly converted as children, and Franciscan friars heeded the Good Book’s warning against sparing the rod. While Serra almost certainly never whipped or beat a native himself, he founded and oversaw nine missions from San Diego to San Francisco where corporal punishment was administered faithfully. In an oft-quoted passage from a 1780 letter to the governor of Las Californias, who was concerned with the harsh treatment of the natives at the hands of Serra’s men, Serra explains “that spiritual fathers should punish their sons, the Indians, with blows appears to be as old as the conquest of [the Americas]; so general in fact that the saints do not seem to be any exception to the rule.”

To make sure the conversions stuck, neophytes were forbidden from ever leaving the walls of the mission, thereby ensuring those who had already been baptized never mixed with the soon-to-be baptized still living on the outside. The punishment for runaways was more of the same: one woman of the Chumash people recalled how her grandmother had been “a slave of the mission” and was whipped so many times that the lacerations in her butt cheeks were crawling with maggots.

All this lead to the decimation of California’s indigenous people. Though hard figures are difficult to come by when dealing with such a time and place, one estimate shows a loss of one-third of the native population in the 50 years following the start of Serra’s missionary work, falling from around 300,000 in 1769 to around 200,000 in 1821. Another estimate suggests that, just 100 years after Serra’s death in 1784, only one-sixth of the population survived.

What should be clear to the God-fearing and the faithless alike is that Serra and his men didn’t introduce civilization as much as hasten the death of one. Their charity was smallpox and The Plague. The cross they carried before them was formed with rifles and swords. At the very least, they initiated a wholesale massacre of the mind and of the flesh.

And this is what the Vatican and its pop-star Pope label as saintly? This genocidal sadist is who the Church chooses to elevate as a moral exemplar for its flock of 1.2 billion strong?

I may be a doomed atheist—non serviam, I say proudly—but I still have more than enough goodness in me to know the difference between a saint and a criminal.

Which is more than I can say for Pope Francis.

***

Hector Luis Alamo is a Chicago-based writer. You can connect with him @HectorLuisAlamo.