On October 31, 1950, a barber looked out the window and saw 40 policemen and National Guard soldiers surrounding his barbershop. “Ay coño,” said the barber, and started to prepare himself.

He dimmed the lights in his shop. He pulled some weapons from a hidden stash, and distributed them around the shop. He prayed to a ceramic statue of Santa Barbara. And then he waited.

Around 2pm, someone walked into the barbershop—a fat man in a black cowboy hat, reeking of rum and cheap cigars. “Nice hat,” said the barber, then shot it off his head.

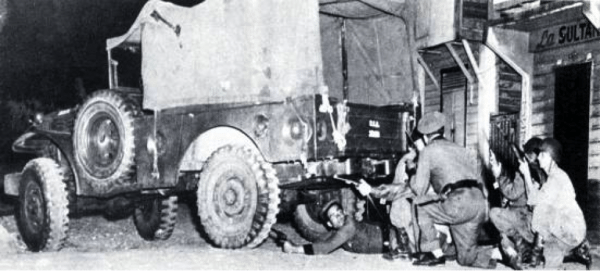

The fat cowboy was an Insular policeman. He ran out of the barbershop and hid behind a military jeep. The Gunfight at Salón Boricua had begun.

The barber was a Puerto Rican Nationalist, and his shop was a neighborhood institution in the Barrio Obrero section of Santurce. It had survived two hurricanes and six useless governors, but this was much worse. No one had ever seen something like this. As the soldiers pulled out pistols, rifles, carbines, machine guns and grenades, the word spread like fire through Santurce: Vidal Santiago Díaz, the owner of Salón Boricua, was in big trouble.

Two dozen National Guardsmen surrounded the shop. Insular policemen took sniper positions on three corner buildings. Then all at once, they fired from every direction. They concentrated on the front door, the windows, the upper balcony, and their machine guns blasted a window gate off its hinges.

But the barber would not go down. Like a caged tiger, Vidal waged a spectacular battle. He shot ceaselessly at his attackers from behind a cement column, from the windows, and even from the very doorway of his shop.

“Jesus!” yelled a soldier. “How many of them are there?”

At around 3pm, the press started to arrive. El Imparcial and El Mundo sent their best metro reporters. Over a dozen radio stations sent mobile units including WIAC, WNEL, WITA, WKAQ (San Juan); WPRB (Ponce); WCMN, WEMB (Arecibo); WSWL (Santurce); WMDD (Fajardo); WENA (Bayamón) and WVJP (Caguas). Even Mayagüez sent a radio unit, from the opposite end of the island.

The Gunfight at Salón Boricua was the first island-wide broadcast of a live news event in the history of Puerto Rico.

Just like the Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast, it had everyone on the island glued to their radio. But unlike War of the Worlds, this one was real.

The most aggressive reporter was Luis Enrique “Bibí” Marrero—and for good reason. He was born and raised in the Chícharo section of Santurce and he knew Vidal personally.

“How many Nationalists are in there?” he asked the National Guard lieutenant.

“Twenty or thirty.”

“Are you sure?”

“Stick around and find out.” The lieutenant had no reason to exaggerate, but Bibí was not convinced.

“Oye, Vidal,” he yelled.

“¿Quién habla?”

“It’s me, Bibí. How you doing in there?”

“I’m all fucked up.”

“¡Coño Vidal, te ha’ hecho famoso! Every radio station on the island is here.”

“I got a radio too. It’s got all this American crap.”

“Do you need anything?”

“Yeah, a ticket to Cuba.”

“Maybe we can arrange it. How many guys are in—”

BANGBANGBANGBANGBANG…

…and Bibí ducked for cover again.

No one was going anywhere that day. Two machine gun volleys gutted the entire building. The stucco facade crumbled. The balcony fell. Almost every door and window collapsed from the .30 caliber shots. But Vidal kept popping up —in one window after another— and firing like a madman.

The gunfight continued for three hours and hundreds of shots were fired. Vidal had an enormous stash of ammunition, hidden somewhere in the barbershop, and he wasn’t shy about using it. At one point two detectives tried to crawl in through a busted refrigerator, and he blasted them back with a shotgun. Then he started singing an aguinaldo, and people started cheering for him in the street.

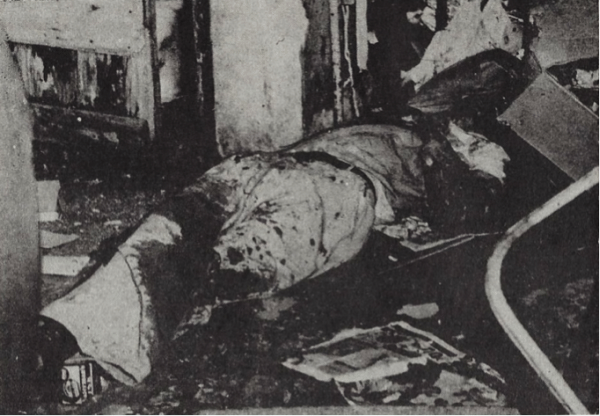

The lieutenant resented this cheering. He ordered the two Browning M1919A4 machine guns to fire continuously. All the mirrors shattered. Glass, shrapnel and chunks of cement flew all around Vidal’s head. Something sliced through his right cheekbone, and took the skin along with it. He was shot four times and lost three fingers—they flew off his left hand and landed somewhere in the blasted room.

The lieutenant yelled “Cease fire!” and grabbed a bullhorn. “Vidal Santiago,” he called out. “We don’t want to hurt you.”

Vidal laughed inside the shop. “Tell that to my hand, pendejo. You shot it pretty good.”

“You and your friends… come out with your hands up, and no harm will come to you.”

“I don’t have any friends.”

“What you do have, is one minute. Come out or we’re coming in.”

“P’al carajo, maricón.”

When a reporter translated this for the lieutenant, he ordered the machine guns to fire again. They strafed the ceiling, vaporized the barber chairs, exploded the walls into hundreds of supersonic rocks, until a staircase collapsed and knocked Vidal unconscious.

A dozen soldiers stormed into the barbershop, but they couldn’t find any Nationalists: just four walls spattered with blood and rubble covering the entire floor.

“Where’d they all go?” said a soldier, as they searched for a hidden exit or a trap door. Everyone expected 30 Nationalists to come staggering out, but the barbershop was deserted—as if they’d been fighting a ghost. Then suddenly a soldier called out.

“Holy shit! Come look at this!”

Everyone ran over and stared at Vidal, in utter disbelief. The barber was covered in blood and broken glass, apparently dead, but just to make sure, a soldier shot him in the head. Then they dragged him out by his feet.

The soldiers were embarrassed: 40 trained men —with machine guns, grenades and full military ordnance— had been battling for three hours with one barber. It was doubly mortifying because the entire island of Puerto Rico heard it live via radio. But then, as they hauled the corpse into the street, things got even worse.

The corpse opened its eyes.

The soldiers jumped and dropped Vidal on the sidewalk.

“Oh, Jesus!” yelled one.

“I thought you shot him!” shouted another.

A third ducked behind a car and started praying. The reporters ran in all directions, taking photos, grabbing their microphones, telling two million Puerto Ricans that Vidal, the little barber from Salón Boricua was still alive!

Within minutes every house, barbershop, beauty parlor, and bodega in Puerto Rico knew about the spectacular heroics of Vidal Santiago Díaz. He became an overnight sensation throughout the island, and a legendary figure in the history of Nationalist politics.

He was the barber who defied an empire, with a bullet in his brain.

***

Nelson A. Denis is a former New York State Assemblyman and author of the upcoming book, War Against All Puerto Ricans.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.