Editor’s Note: Originally published at Chicago Now.

In order to be politically active, we have to believe in our political efficacy: we have to believe that our votes make a difference.

In October, the Pew Research Center reported that 23 million Latinos were eligible to vote in 2012, but only 11 million voted. Pew projected that 27 million Latinos would be eligible to vote in 2016.

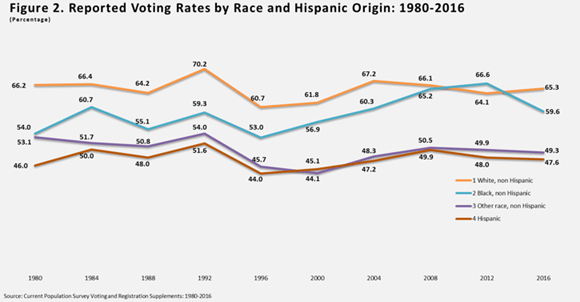

Last week, the United States Census Bureau released information about November’s Latino vote. Only 47.6% of Latinos eligible to vote actually voted. In 2012, 48% of Latinos voted. The sleeping giant still hasn’t woken up. Unless significant changes happen in education and jobs, voting rates won’t change.

In order to be politically active and work for change, we have to have experienced a transformation ourselves. This transformation really only comes through a stable job that leads to good income and stable life. Or through education, which can open up new opportunities.

Latino communities struggle in both of these areas.

It’s true. More students graduate from high school: the drop out rate now is around 12%. When I started teaching twenty-one years ago, we talked about a 50% drop out rate.

Today, more Latinos enroll in college: 35%. But a 2014 survey of Latinos in their mid to late 20s found that only 15% earned a bachelor’s degree or more. Only 11% of low-income, first-generation college students who enroll in college earn a degree. In college, we face a new drop-out rate.

Research (and common sense) tells us that the more educated a person is, the more progressive (or liberal) he or she is.

What makes a difference in college completion? According to most of the research about college success from the University of Chicago’s Consortium on School Research: look at how many students who enroll in a college actually graduate.

An easy way to increase this is to provide support systems, such as student mentors, to help students navigate the complicated world of college life.

One change our Latino families can make to improve education outcomes is to look at how we spend our money. I’m hearing over and over from many high-achieving Latino students that “FAFSA didn’t give me anything.” Or “My parents don’t have money.”

But then I find out that a sister had a quinceañera that cost thousands or that the son was given a new car. Materialism and consumerism have manipulated our thinking so that a college education —perhaps because it’s not tangible— becomes a luxury.

And then there’s credit card debt. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that Latino customers were contacted by debt collectors about credit cards more than whites. While 54% of Latinos contacted discussed credit card debt, less whites contacted discussed the same issue: 44%.

In terms of debt, the difference between what Latinos owe and own is around $13,000. The difference between debt and assets for whites: around $134,000.

The median income for Latinos is around $13 an hour. For whites it’s around $19.

Systemic issues perpetuate this inequality and lack of political efficacy. So does spending thousands on a quinceañera instead of a college degree.

Add to this the fact that many Latinos still work toward establishing roots. The Latino community outside of the Southwest U.S. or in communities like South Chicago is relatively young. People also still hold strong ties to their native land.

When people are asked “¿De dónde eres?” “Where are you from?”, many people on Chicago’s Southwest side still mention a Mexican state—even if they’ve been in Chicago for decades, even if they probably will not return to their native town to live.

I’m not encouraging turning their back on their homeland. Identity is personal. But I think that also gets in the way of seeing themselves as a political force in the U.S.

Plus, it’s difficult to organize around issues. The African American communities, wherever they are in the U.S., have a tie to a common history in this country. For Latinos, every ethnic group has had a different reality. Mexican is not Cuban and that’s not Guatemalan.

There are differences based on generations, too. My Latino students even if they are first generation live a different reality than mine when I was their age.

Bottom line: an obstacle to increasing the Latino vote lies in the strong division between survival and sustainability.

We need to see a college education as a priority worth investing in—worth buying. And Latino students need to major in viable degrees—don’t major in psychology. There’s nothing worse than getting a college degree that opens few doors for a low-income, first-generation college student.

A stable income from a marketable degree would help with housing—and housing needs to become affordable. Even the researcher who once advocated for “creatives” to move into cities now sees the damage this has done. Richard Florida’s solution: raise the minimum wage so it takes into account the cost of living and provide affordable housing near public transportation.

Finally, we need leadership —especially Latino leaders— to build movements around the multitude of issues affecting our communities. Too often, Latino leadership is about politics: whose side are you on? One thing Latino leaders accomplish in politics (and the nonprofit sector) is dividing people.

We find one Latino leader and grab on to that person with all our hopes. Charisma often trumps qualifications.

To help young people make this distinction, teachers can create opportunities for learning that goes outside of the classroom through writing, art, organizing. Last academic year, a teacher at Roosevelt High School in Chicago helped students organize to improve school lunches. Like they did there, students need to learn about the steps to political action.

And it would help if parents learned some English. While it’s not the official language, it makes a difference. People who plan to live and work and thrive in the U.S. benefit when they speak English.

Learning some English would also give them access to other media outlets. Most Spanish media is soaked with sensationalism and info-tainment. There are few easily accessible options in Spanish that provide deep analysis and insight on Latino issues.

Stable jobs, affordable housing, access to get through college, political awareness—these are the ways to increase the Latino vote.

Because when people see their effort transforming their own lives, they will see voting as a need and a personal responsibility—not as something that’s done by someone else, somewhere else.

***

Ray Salazar’s White Rhino Blog is at Chicago Now. The blog also has a Facebook page. Follow Ray on Twitter @whiterhinoray.