Inside Marcial Ayala’s quaint studio in Cusco, Peru, his finished, vibrant, and glamorous paintings hang on one wall and satirical sketches of Michael Jackson, Abraham Lincoln and Jesus hang on another. There’s a bookshelf, filled with books, magazine cutouts and small paintings. Against a wall by the door, his larger paintings rest, as well as empty frames waiting for his new work to fill.

When I ask Ayala to describe his art —that spans graphic design, paint, and collage— he says simply: “an insult to society.”

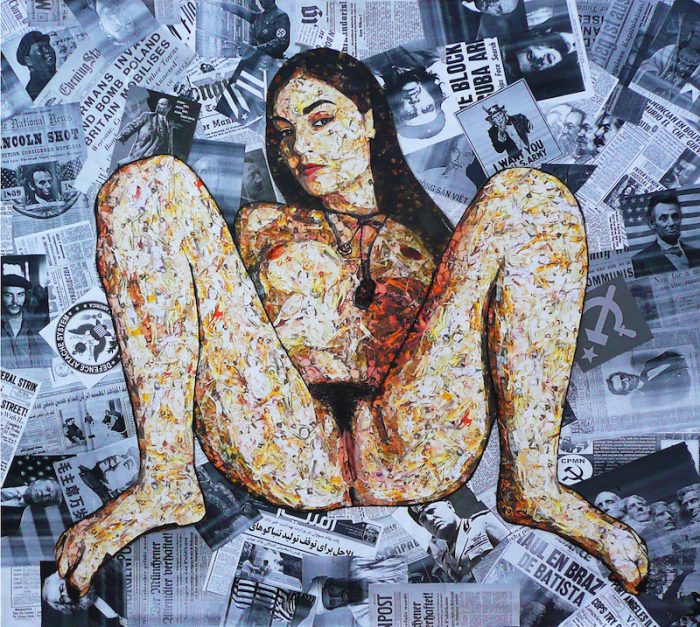

Peruvian women are center canvas in the majority of his art. Ayala portrays them as sexually liberated, like in “Sasha Grey,” where he collaged tiny images of pornography to craft the woman’s body. Hot pink yarn bunch at her crotch, and she lounges, legs open, on a bed of international newspapers that capture some of the world’s most polarizing figures, such as Che Guevara, Osama Bin Laden and Donald Trump.

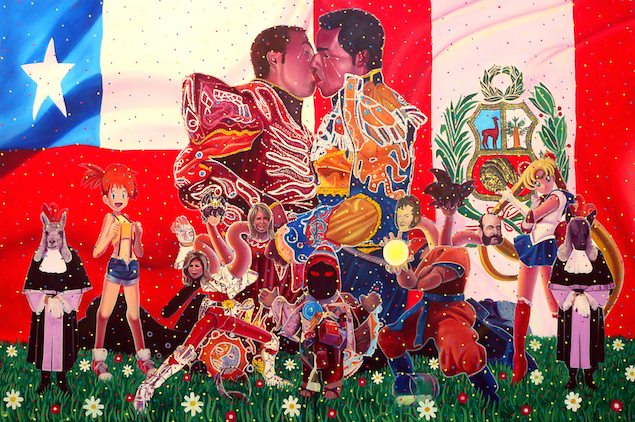

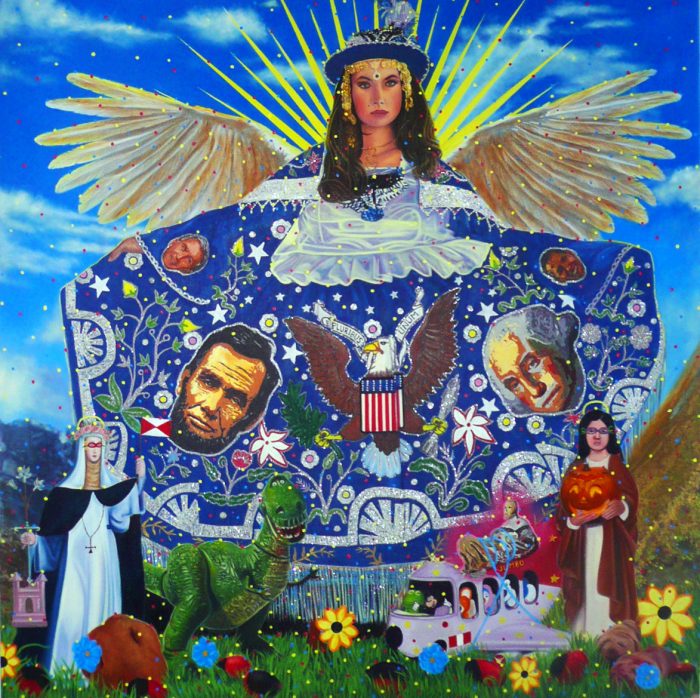

Other themes in his work are lesbianism, communism and religious satire. For Ayala, there’s a clear mission to provoke, and to challenge “the political, religious and sexual repression” that he said defined his upbringing in Peru.

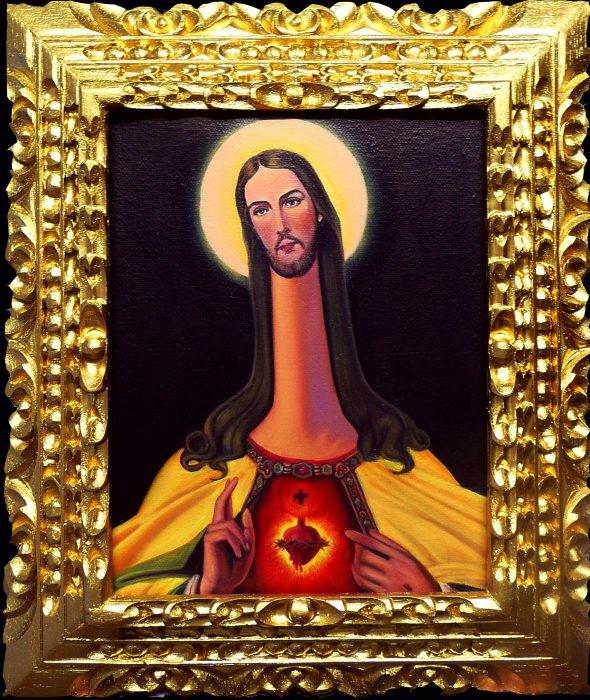

Minus the obvious skill of his work, it’s hard to believe the 33-year-old Ayala started his artistic journey with classic painting in high school. Although he was first inspired by, and has always been interested in religious paintings, that quickly transitioned into the more erotic, satirical and contemporary art most reflective in his work today. Ayala’s motivation is personal expression and provocation.

“Before, people were more ignorant,” Ayala says candidly of Peruvians, “and the people lived with a lot fear and with a lot of complexes.”

“There there was a very strong racial complex,” he continued. “Before the social classes weren’t as mixed. The whites in one place, the mixed people in another place, the indigenous in another. There was a lot of racism.”

No topics are too taboo. What inspires Ayala most, “more than the images, is the want to respond to society,” he said.

Despite Ayala’s penchant to interrogate the status quo in Peru and ridicule any and every political and religious figure worldwide, he admits that things are evolving. “We have changed a lot,” he said. “The internet has been very important for that change.”

Ayala believes a cultural and artistic revolution in Peru is underway, though, Lima receives most of that recognition. Meanwhile Cusco’s artists are repeatedly overlooked.

“If you go and visit the private galleries of Lima, you look at the list of artists, there isn’t a single one from Cusco,” Ayala said, and even though he’s adamant about the thriving artistic talent in Cusco, it’s a city often described as “historically rich,” yet rarely artistically.

But the Cusco area is not just a place for tourists to rest their heads on the way to Machu Picchu, or a central point to visit the Inca ruins that surround the city, but rather a haven for contemporary and radical art, Ayala says.

Despite the impediments of being an artist from Cusco, Ayala has certainly been one of the frontrunners to break through. In 2003, the same year he began his training at the School of Fine Arts Cusco, Ayala became a finalist in the Siart Bienniel, an art competition in Bolivia. Since then, he’s shown his work in Lima many times and won third prize in the “Passport for an Artist” contest in 2011, which allowed him to travel to France and participate in an exhibition in Paris. Two years later, he won first prize in an art competition organized by the Brazilian embassy in Peru.

Yet Ayala’s solo success has not stopped him from spearheading a larger movement: to move Cusco’s marginalized artists to the country’s center. In 2013, in collaboration with a diverse group of Cusco artists, the artistic collective “Uku Pacha” (meaning under world in Quechua, the language of the Inca empire) was formed, and its artists have showcased together in Cusco and Lima. But Ayala and Uku Pacha still labor for Cusco’s proper recognition as a cultural center for contemporary art.

Title: FREEDOM GUIDING THE PEOPLE 3

Technique: Collage on Wood (By Marcial Ayala/Used with permission)

Nevertheless, Ayala is paving the way. This year, his work was featured in a solo exhibition in the city’s Museo Municipal de Arte Contemporáneo. His art is visible, and so his advocacy for Cusco’s artists, and his goal of breaking down the elitist barriers that keep Lima’s galleries closed is palpable.

But not without a little humor. When I ask Ayala, how much of his work —filled with hyperbole, insult and erasure—is satire?

He grins: “all of it.”

***

Rachel Leah is a culture writer for Salon and in general, explores news through the intersections of race, class and gender. She tweets from @rachelkleah.