By Rafael Bernabe and Manuel Rodríguez Banchs

Dear Friends:

By now you have surely heard about the catastrophic impact of Hurricane María in Puerto Rico, as well as the slow and still inadequate response by U.S. federal agencies, such as FEMA.

A month after María, dozens of communities are still inaccessible by car or truck. More than 80 percent of all homes lack electricity. A third of the island lacks running water. Many of Puerto Rico’s 3.2 million residents have difficulties obtaining drinking water. The death toll continues to rise due to lack of medical attention or materials (oxygen, dialysis) or from poisoning caused by unsafe water.

The failures of U.S. agencies might come as no surprise, since the federal response (including FEMA’s) to other disasters, such as for Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, was as slow and inadequate.

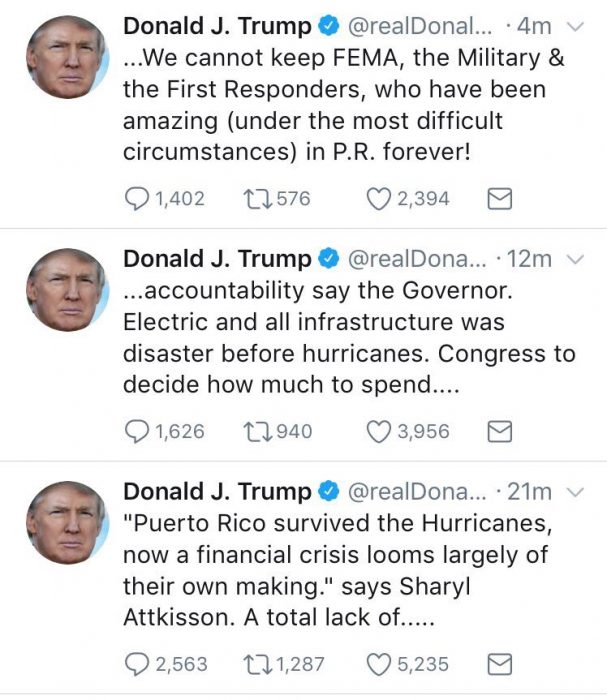

You may have also heard President Trump state that Puerto Rico was dealing with a debt crisis before the hurricane and that its electric grid had been allowed to deteriorate. As far as they go, these statements are true.

But President Trump also tweeted suggestions that Puerto Rican workers are lazy and that FEMA and other agencies cannot remain in Puerto Rico forever. This spins the notion that Puerto Ricans are themselves to blame and should not expect any more handouts. Trump aims to build a wall between us, which doesn’t come as much of a surprise either, by portraying us as a burden, as illegitimately claiming resources to which we have no right.

Through the media you may have also heard that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens as well as a nation, a people with its own identity and culture, under U.S. colonial rule since 1898. Sometimes these facts generate confusion regarding Puerto Rico’s relation with the United States.

Dear friends, contrary to what the President would have you believe, Puerto Rican workers are neither lazy, nor do they want everything done for them (as he also tweeted). They wish for the same things that most American working people want: jobs and adequate income; appropriate housing, education, health services and pensions; dependable infrastructure and livable neighborhoods, along with protection of the environment. Working people in the United States and Puerto Rico share the same interests. We have common needs. The effort to rebuild Puerto Rico should help us understand this fully, regardless of the political path Puerto Rico eventually follows, be it toward independence, statehood or some form of sovereign association with the United States. To better understand this joint agenda, we’d like to share a few historical facts.

Puerto Rico has been a colony of the United States since the Spanish-American War of 1898. Puerto Rico was legally defined as unincorporated territory, a possession but not part of the United States, under the plenary powers of Congress. Although Congress has reorganized the territorial government over the years, up to the 1952 creation of the present Commonwealth status, the colonial nature of the relationship has remained unchanged. Puerto Ricans elect their governor and legislature, but they only attend to insular matters. We remain subject to both federal legislation and executive decisions, even though we have no participation or representation in their elaboration. Since 1898, Congress has never, we repeat, never consulted the Puerto Rican people in a binding plebiscite or referendum on whether to retain the present status, become independent or a state of the Union. Having retained its plenary powers, Congress should assume responsibility for a territory it claims as a possession: yet it has often skirted that responsibility. This again should come as no surprise, as Congress has often ignored and overlooked many unjust situations in the United States (affecting workers, women, African-Americans, Native Americans, immigrants, among others), unless activism and mobilizations forced it to do otherwise.

But colonialism has an economic, as well as a political, dimension. After 1898, Puerto Rico’s economy came under the control of U.S. corporations. Puerto Rico then specialized in producing a few goods for the U.S. market. One consequence has been the constant outflow of a significant portion of the income generated in Puerto Rico. At present, around $35 billion leave annually. This is around 35 percent of Puerto Rico’s Gross Domestic Product.

This capital is not reinvested and does not create employment here in Puerto Rico. Thus, Puerto Rico’s one-sided, externally controlled and largely export-oriented economy has never been able to provide enough employment for its workforce: not when sugar production was the main industry; not in the 1950s and 1960s with light-manufacturing that came and often went; not today, through capital intensive operations, among which pharmaceuticals are the most important.

This dependent and colonial nature of Puerto Rico’s economy lies at the root of the high levels of unemployment, not the alleged laziness of Puerto Rico’s workers, an old racist stereotype now taken up by President Trump.

At present, Puerto Rico has a 40 percent labor participation rate. That is to say, 60 percent of its working-age population is out of the formal labor market; they have abandoned all hope of finding a job. Of the 40 percent that are still in the labor market, around 10 percent are officially unemployed.

Mass unemployment depresses wages, which deepens inequality, and creates high levels of poverty. This helps explain the persistence of the wide gap in living standards with the U.S. mainland. After more than a century of U.S. rule, Puerto Rico’s per capita income is half that of the poorest state, Mississippi. Around 45 percent of the people in Puerto Rico live under the poverty level.

Lack of employment has resulted in considerable migration to the United States, with the Puerto Rican population stateside now at 5 million. Historically, Puerto Ricans have been incorporated into the U.S. working class as one of its discriminated and over-exploited sectors, along with African-Americans and other fellow Latinos. Deeply connected and concerned with the situation of their homeland, they are also part of a multiracial and multinational U.S. working class.

Given the levels of poverty, it is not surprising that many in Puerto Rico participate in federally funded welfare programs. That is to say: considerable public funds are spent to partially mitigate the dire consequences of a dysfunctional colonial economy. To put it otherwise: the present situation, while profitable for a few corporations, is a disaster for both Puerto Rico and U.S. working people. Therefore, it is in the interest of both that Puerto Rico acquires an economy capable of providing for its inhabitants without requiring such compensations.

Since 1947, certain exemptions from federal and island taxes was one of the means of attracting foreign investors. Yet, in 1996 Congress began phasing out the federal tax exemption, which was completed in 2006. Make no mistake: tax exemption was never able to guarantee development or employment.

But Congress replaced an inadequate mechanism with, well… nothing.

A broken crutch may be of little help to a limping person, but simply removing it is even worse. As a result, manufacturing jobs have fallen by more than half since 1996. Puerto Rico’s economy has shrunk since 2006. More than 250,000 jobs have been lost; 20 percent of the jobs that existed a decade ago have vanished.

But Congress does not bear all the blame. As Puerto Rico’s economy collapsed, its government did not re-evaluate its priorities. It did not seek, for example, to recuperate a larger portion of the profits leaving the island through taxation or other means. Instead, it took on massive debt. Meanwhile, electrical and other infrastructure was allowed to deteriorate, often to generate support for privatization. The situation could not be sustained: by June 2015 the government had to admit that its debt is unsustainable and would have to be renegotiated.

Congress then adopted the Puerto Rico Oversight Management and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA). It created a non-elected, federally-appointed control board, with broad powers over Puerto Rico’s state finances. It provides no funds or measures for economic recovery. It enables austerity policies that deepen poverty while perpetuating the present depression. In other words, it is anti-democratic, colonial, socially unjust and economically counterproductive. Under the fiscal plan it certified, no growth is foreseen until 2024! Again, this may not come as a surprise: this has been the formula (layoffs and cutbacks) applied against working people in dozens of budget crises, from New York City in the mid-1970s to Detroit in the recent past.

Proposed government cuts come after other austerity measures such as new sales taxes (IVU, 2006); mass government layoffs (Law 7, 2009); attacks on public sector labor rights (Law 66, 2014); reduced public employment through attrition (90,000 jobs eliminated since 2006) and rescinding labor rights in the private sector (2017).

What does Puerto Rico need? We need an adequately funded program of economic reconstruction (including the transition to renewable energy), the powers to carry it out and a true process of political self-determination. Congress can and should provide funds for reconstruction, which also requires the cancellation of Puerto Rico’s public debt. This debt was already unsustainable; to collect it now would be criminal.

You might rightfully ask: why should Congress allot billions for reconstruction in Puerto Rico, when it does not do so in the states? Our answer: it should do so in the states as well! After all, working and poor people in the United States are suffering the social and environmental consequences of decades of neoliberal economic policies. As much as we do, American working people need a vast program of economic reconstruction, geared toward creating jobs and addressing social needs.

We draw inspiration from the many movements with similar objectives in the United States: to tax corporate profits, for job programs, urban reconstruction, expanded social services, universal health insurance and free higher public education, renewable energy, student debt cancellation and relief for indebted families, reduced military in favor of social spending, to organize workers and revitalize the labor movement, to end all forms of racist, sexist, homophobic or xenophobic discrimination. We in Puerto Rico need these movements as much as you do. We count on you to build and expand them. And we ask that you include Puerto Rico’s needs for economic reconstruction, debt cancellation and self-determination in your demands and proposals.

The limitations of one-sided dependent development are not the result of restrictions on movement of capital between Puerto Rico and the United States. They are, if anything, the result of the unfettered action of private interests. In other words, the dogmas of privatization, deregulation and free trade fundamentalism are part of the problem, not the solution. We need a planned reconstruction of our economy, with broadened public and cooperative sectors. Such plans must be elaborated in Puerto Rico, not by federal programs or agencies beyond our control or supervision.

The same holds true in the United States, where budget deficits are not the result of over-generous social programs, but of low corporate taxes, and, after the crisis of 2008, of government debt to bail out the banks from their own speculative excesses.

Over the years, much of the product of our labor has left the island, not unlike much of the wealth created by U.S. workers is taken by a fabulously rich corporate caste. This harsh reality demands that the fight against these ills —colonial and class exploitation— advance jointly. To those who threaten “No bailout for Puerto Rico” we respond: it is high time we invest in the people of Puerto Rico and of the United States—and stop protecting the privileges of banks and large corporations!

Let us work together then for justice: justice for working people in the United States and for immediate and adequate hurricane relief, as well as lasting economic reconstruction, debt cancellation and self-determination in Puerto Rico.

Sincerely,

Rafael Bernabe

Manuel Rodríguez Banchs

***

Rafael Bernabe is a researcher and professor at the University of Puerto Rico. He is the author, with César Ayala, of Puerto Rico in the American Century: A History Since 1898 (2007). Manuel Rodríguez Banchs is a labor lawyer and social justice advocate. Both belong to Working Peoples Party in Puerto Rico.