By Evelyn Milagros Rodríguez, University of Puerto Rico, Humacao

I’ve always been fascinated by storms, particularly Puerto Rico’s own history of them. I think it’s because I was born in September 1960 during Hurricane Donna. In its wake, that storm left more than 100 dead in Humacao, the city where I am now a special collections librarian at the University of Puerto Rico.

In 1990, Israel Matos, the National Weather Service Forecast Officer in San Juan, told me that, “The tropics are unpredictable.” That comment only increased my interest in storms. Now, with the people of Puerto Rico still reeling from Hurricane Maria more than a month after it hit the island, his words seem prescient.

Today I have —if not the honor, then the duty— to describe, firsthand, what it is to live through the aftermath of the worst storm of this brutal hurricane season.

Academic Crisis

Since the storm, I haven’t been able to go to work at the library on the Humacao campus. At 88,000 square feet and three stories, the biblioteca is the biggest building on campus, and it’s among the worst damaged by Maria.

The library at the University of Puerto Rico, Humacao. (Evelyn M. Rodríguez, Author provided)

It’s mold-infested and the roof is leaking, so there’s a lot of work to be done in both repairs and cleaning before students can use it. The mold has gotten into our collection —from books and papers to magazines— and most of the furniture and computers will have to be replaced.

According to the general damage report for the University of Puerto Rico, the infrastructure in all 11 campuses of the university system suffered severe losses.

The Humacao campus, located on the island’s eastern side, was the hardest hit, with damages calculated at more than $35 million. Classes will start again on October 31.

Students at the Río Piedras campus, which has been partially closed since Hurricane Irma skirted Puerto Rico on September 6, have had only a week of class so far this year.

Five weeks after Hurricane Maria, all the campuses have now reissued their academic calendars and classes are resuming, though in some places the first semester will run through January to make up for lost time.

A Culture of Catastrophe

Starting on September 20, Hurricane Maria swamped Puerto Rico with 20 inches of rain and battered it with 150 mph winds for over 30 hours.

The resulting humanitarian crisis has been widely reported worldwide: power generation is only at about 30 percent and there is not enough drinking water.

Communications —radio, television, telephones and internet— are now recovering slowly, after weeks of near nonexistence. Having said that, it took me more than two weeks just to write this article, between finding somewhere to charge my laptop and locating an internet connection strong enough to research the data and send a file by email. Eventually I discovered a Starbucks near my house with both electricity and Wi-Fi. Nothing is easy.

What outsiders are unable to see, perhaps, is that an entire culture has arisen around the catastrophe caused by Hurricane Maria—one with typically catastrophic traits: material scarcity, emotional trauma, economic catastrophe, environmental devastation.

Puerto Ricans are now facing a dramatically different way of life, which means our relatives and friends in the diaspora are, too.

Nothing about life resembles anything close to normal. An estimated 100,000 homes and buildings were demolished in the storm, and 90 percent of the island’s infrastructure is damaged or destroyed. Not only are there shortages of water and electricity but also of food, highways, bridges, security forces and medical facilities.

It’s unsafe to venture outside at night. An island-wide curfew was lifted last week, but without streetlights, stoplights or police, driving and walking are dangerous after dark.

The official tally of missing people varies, with police tallies ranging from 60 to 80 right now. Considering Puerto Rico’s hazardous conditions and limited health care services, that number is sure to rise. We are well aware that epidemic diseases, including leptospirosis and cholera, could come next. Health concerns are further stoked by the delays and disarray of the various federal agencies tasked with handling this emergency.

A deep uncertainty looms over our futures. There is post-traumatic stress involved in surviving in an overwhelming situation like this, so as a people we’re now waking up to that psychological pain, too.

The Outlook From Here

In short, Hurricane Maria has changed the modern history of Puerto Rico. For those who, like me, are curious about such things, the last storm of this caliber was San Felipe II, in 1928.

Known in the U.S. as the Great Okeechobee Hurricane, that massive storm was so destructive that it basically plunged Puerto Rico and Florida into the Great Depression a year before the rest of the country.

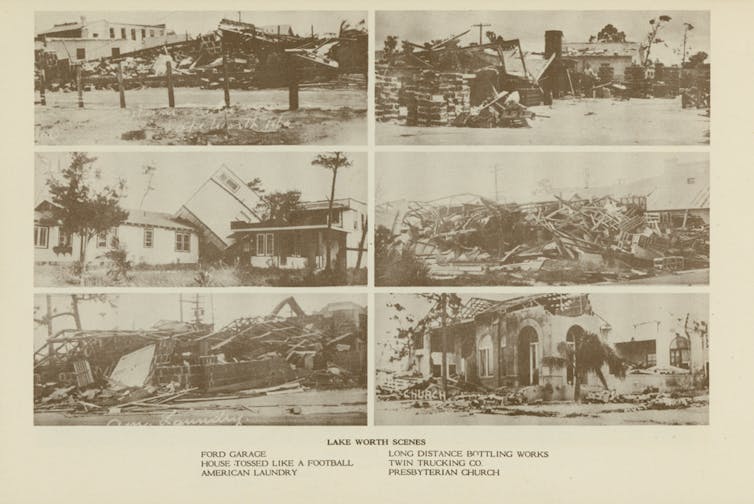

The aftermath of the Great Okeechobee Hurricane in Florida, 1928. (NOAA)

In some ways, though, Puerto Ricans are well prepared for these challenges, for the history of the island is one of uncertainty and trouble.

Puerto Rico has never had a sovereign government. Instead, it has always been bound to some other larger and more powerful state. First it was Spain, which colonized our territory in 1508.

Then, since the 1898 invasion, it’s been the United States, a country with which Puerto Rico enjoys a tricky political relationship. That’s very clear right now, as the Trump administration wavers in coming to our aid.

Mired in Uncertainty

Even before the hurricane arrived, Puerto Rico was facing uncertainty around another major challenge: bankruptcy. Considering lost pensions, jobs and savings, the real financial costs surely exceed by billions the official sum of $123 billion in unpaid government debt.

Hurricane Maria has deepened this economic crisis, creating a ripple effect that touches everyone across all levels of society.

Everyone is mired in uncertainty. What is the solution to this cascading set of problems? How long will recovery take? What could actually make life better for us? What will we miss? Will anything ever be the same?

Among all this concern and confusion, though, some things have become clearer since the storm. On this once-green island, the hurricane blew down and shredded thousands and thousands of trees.

The sky is more visible now. Houses once hidden are exposed, and we discern entire communities that that we rarely saw before.

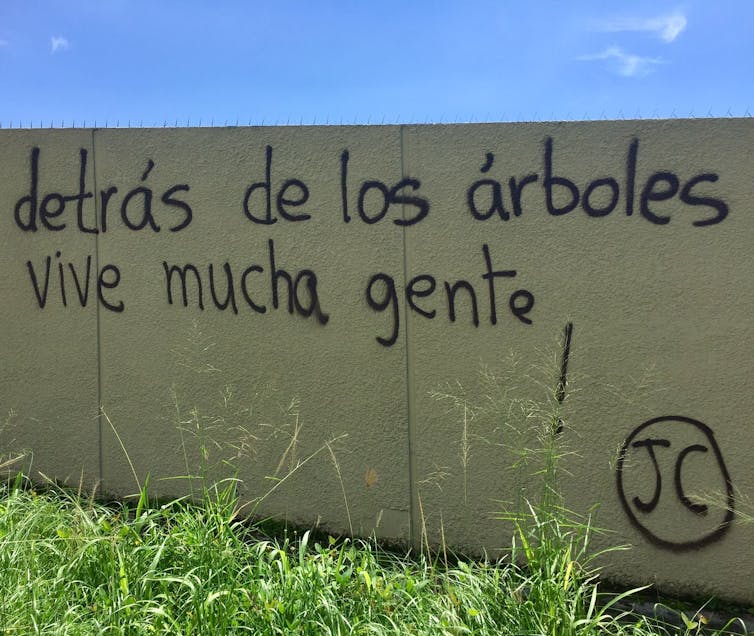

A graffiti-scrawled reminder in Puerto Rico: ‘Behind the trees live a lot of people.’ (Evelyn M. Rodríguez, Author provided)

There’s graffiti popping up across the island, written by someone identified as “JC,” who reminds Puerto Ricans, as a kind of consolation, that “Behind the trees live a lot of people.”

Just as new environments are created in areas opened up by the hurricane, with trees and plants sprouting afresh, over time we’ll find that our current uncertainties also fade and transform. A brand new way of life is emerging among all Puerto Ricans—those who stayed, those who left, their relatives and their friends.

![]()

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.