Growing up, Speedy Gonzales was, literally, the only children’s character (cartoon, book or otherwise) who was anything like me. Since I’m not a mouse or from Mexico, the only thing Speedy and I actually share is a surname. Still the kids at school would shout, “Arriba, rriba, ándale, ándale,” as I walked by. When the boy I thought liked did it, I’d smile and force a laugh; when others did it, I lowered my head and pretended to disappear.

Last winter on Facebook it was a thing to change your profile photo to a character from a children’s book character who was most like you, and I wanted to play along, but I couldn’t think of any children’s book character who was like me or who I identified with. I posted a photo of Speedy Gonzales. Speedy was all I could think of, and I wanted to make a point about a lack of diversity in children’s literature. Not having grown up in the internet age, it was the first time that I learned that something seemingly trivial on social media could make me feel so invisible and so sad.

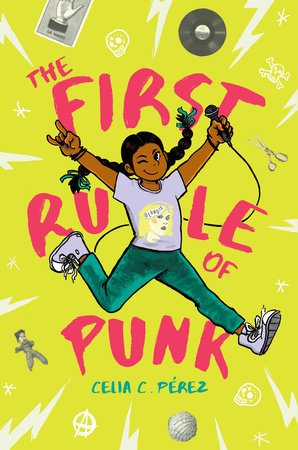

And so, in spring 2017, the news of the upcoming middle-grade novel, The First Rule of Punk by Celia C. Pérez, came as wonderful surprise. I was on social media, of course, and I came across an article announcing the upcoming release of the book which contained jpeg of the cover art—an illustration of a brown-skinned pre-teen with braids and a Blondie T-shirt. The title jumped out at me too because it’s similar to the title of my own book, and because it’s a kids’ book about a punk girl. This point bears repeating: a kids’ book about a brown-skinned girl and punk rock.

As I read the article, clicked around the webpage, enlarged the image, scrolled the page, and read as fast as I could, not realizing that I was holding my breath until I exhaled loudly about to cry. My heart pounded in my chest—not once in my life had I seen a book (fiction) about someone so much like me. There are books by Xicanas about Xicanas who have had some of the same feelings that I have had, like Teresa in Ana Castillo’s Mixquahuala Letters or Esperanza in House on Mango Street, but never so many experiences, never a punk rock Latina teenager.

When I got an advance copy of the book in summer, I read it in two sittings. I took pictures of myself with the book and posted them on social media, told all my friends about it, and ordered copies for my nieces whose parents are from Mexico.

I gave it to them for Christmas, here is a book that will help you understand your wild, pre-menopausal, punk rock, drum-playing, f-word-wielding tía.

Since reading the book last summer, I have thought a lot about it, fixated on the idea that such a book can even exist. I haven’t quite gotten over the fact that a major publisher, Penguin Random House, would even publish a book like The First Rule of Punk for young people. What’s more is that the book was published just after the election and inauguration of a proud white nationalist—the current president of the United States.

It doesn’t surprise me that publishing houses are more progressive than the office of the presidency, but I do know that because they are in the book-selling business, that they do sometimes underestimate what the American public will read, and who is doing the reading.

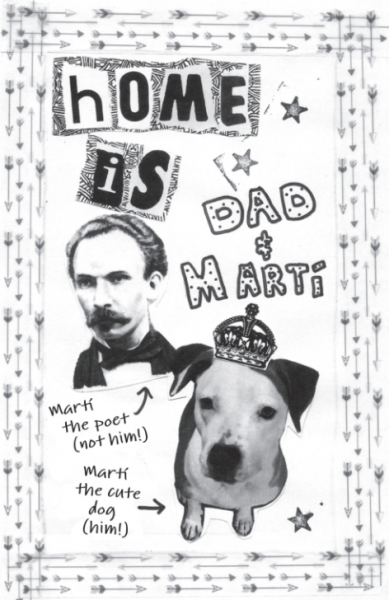

Artwork from The First Rule of Punk

Fortunately for book publishers, punk, or the idea of it, the commodification of teen angst and silver studs on clothes when you’re feeling edgy (now ubiquitous in the fashion industry) has become mainstream. As a writer who has published a book on the topic of punk, I have benefited from the commodification of punk rock, and from the ways in which punk, teen angst, and resistance movements are better understood, but when I was growing up in the 1980s, punk rockers equaled gay, kinky, homicidal, or worse, communist.

Still it’s hard to imagine that while author and librarian Pérez was busy writing her middle-grade book about young Malú, the middle school Latinx with a type-A Mexican-American mom, and a laid-back white American record-store-owing dad, a self-serving, megalomaniacal white supremacist was making a run for the White House.

While Pérez was busy adding beauty to the world, making girls like me visible (girls who are currently middle-aged women who had to wait this long for such a thing to happen), our now president was calling Mexicans rapists, demanding walls, Muslim bans, and regarding anyone who opposed him who were inspired by European punks to form anti-fascist groups in the 70s and 80s as deranged radicals.

It’s hard to reconcile.

It’s especially hard to reconcile because while I no longer feel invisible, there is a sense of déjà vu. From 1983–1989, I was Malú or Maria Luisa, a weirdo, musical, punk rock Latina, living under Ronald Reagan, the cowboy president. I was bullied by peers and teachers (yes, teachers) for being brown, shabby, and poor. Mr. Rundle, my racist and classist teacher who wouldn’t do anything about the boys who tripped my chubby, poor, orphaned white friend, instead asked if I was Italian, and scoffed when I said, “No, I’m Mexican,” and the school janitor who said, “You’re pretty bold for a Mexican girl,” when I accidentally stepped on her freshly mopped floor, were no doubt emboldened by the cultural climate—by Reagan, who had once fought Indians on the big screen, called my mom a welfare queen, and sowed fear about foreigners, the Cold War, Russians, and commie American traitors.

And while I’m not mixed race like Malú, I am a third generation Mexican-American, a Xicana, who sounds white, speaks weak Spanish, and who even now at 48t spends a lot of time listening to her inner punk girl. My inner punk girl is the angsty teen inside me who turned to punk at 13 after being othered, ridiculed, and bullied. Like Malú, but in real life, I started the band Bitch Fight in 1985 with my school friends: a mixed-raced Xicana and a white girl. All three of us were poor and had single moms who paid for their groceries with food stamps.

See us, hear us, come to terms with the fact that we exist—it’s what Bitch Fight, demanded.

Growing up under such circumstances and with what would have been an 8 on the ACE score, it would have been a great comfort to have read about a girl like Malú and because positive messages about girls like me did not exist when I was growing up, is probably why I turned to punk in the first place. Punk is good place to go when you’re not feeling heard, when you need a song that matches how you feel inside. Literature is good for this too. And so finally we can have both, and young girls who like art, making zines, who are marching band nerds, like weird music, and/or who aren’t conforming to gender norms have their own book. And thanks to Celia C. Pérez, I have Malú, a character who is like me from literature whose photo I can post on social media the next time I need it.

Artwork from The First Rule of Punk

***

Michelle Cruz Gonzales, a Xicana writer, writes memoir and fiction. Born in East LA in 1969, MCG grew up in Tuolumne, a tiny California Gold Rush town. She played drums and wrote lyrics for three bands during the 1980s and 1990s: Bitch Fight, Spitboy, and Instant Gir. Currently, MCG is at work on a satirical novel about forced intermarriage between whites and Mexicans for the purpose of creating a race of beautiful, hardworking people. She lives with her husband, son, and their three Mexican dogs in Oakland, California. She tweets from @XicanaBrava.