A general election was held in Honduras on November 26, 2017. The candidates were incumbent Juan Orlando Hernández and Salvador Nasralla, a former sportscaster and television personality. On November 27, Nasralla appeared to lead, holding a five-point advantage, as multiple media outlets appeared to report. The New York Times reported that “with results from 57 percent of the polling sites counted, Mr. Nasralla led Mr. Hernández by almost five percentage points;” Reuters reported that “with 70 percent of ballots counted,” Nasralla was “practically the winner,” according to Marcos Ramiro Lobo, one of four election tribunal magistrates.

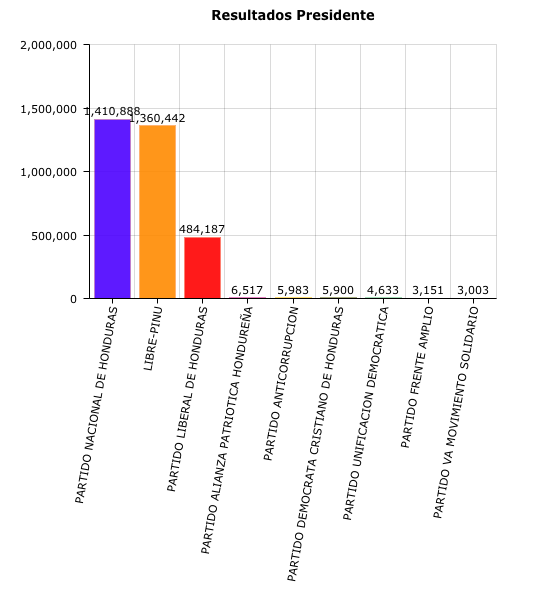

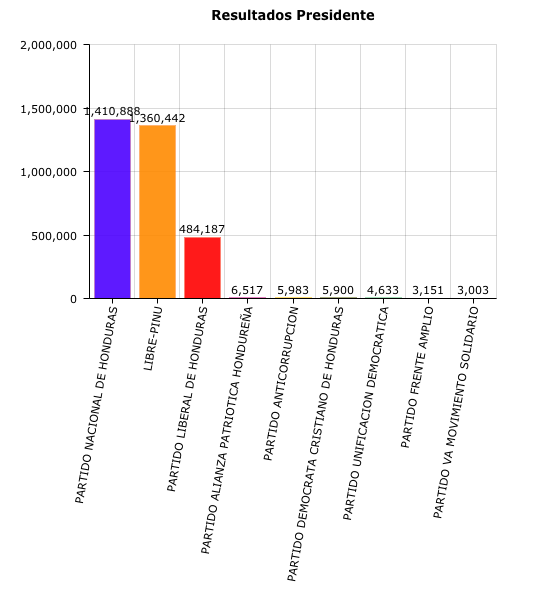

The “insurmountable” lead vanished, and on December 17, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) had declared Hernández, the President of Honduras. This is how the race shifted. (Hernández votes are in blue and Nasralla votes are in orange.)

Analysis from The Economist found that, “if results released from the TSE at each stage were a representative sample… the odds of the shift it reported from Mr. Nasralla in early results to Mr. Hernández in later ones would be close to zero.” The report states the possibilities of statistical anomalies, such as Mr. Hernández’s claim of support from rural areas, is supported by “a large number of voters living in urban areas that reported early and many living in late-reporting areas.”

Claims of electoral fraud appeared to be supported by evidence, specifically a recording, that if “authentic,” supported the allegations from the opposition. The recording featured a woman, a self-identified government employee, “teaching” techniques that included obtaining polling credential from smaller parties, allowing multiple votes for National Party voters, and altering votes during the counting process.

The New Yorker featured a compelling commentary on the counting process, that appeared to corroborate such a report. In Honduras, voting occurs at around “18,000 polling stations… about 16,000 of which have the technology to scan vote tallies… and send them to the electoral tribunal digitally.” Of these 12,000 sent results, 5,700 were unaccounted. An interview with an official hired to tabulate ballot data, relayed a general unease: “We were in the control room at election headquarters during the day, and we could see on a screen that sixteen thousand polling places were online and ready… We had the data, but the tribunal wasn’t saying anything. We didn’t know what was going on.”

International bodies that observed the election doubted the quality of the election. The General Secretariat of the Organization of American States (OAS) released a statement that claimed the “electoral process was characterized by irregularities and deficiencies, with very low technical quality and lacking integrity.” The preliminary report from the OAS Electoral Observation Mission (OAS/EOM) and a preliminary statement from the European Union Electoral Observation Mission (EU EOM) agreed, citing several irregularities in the electoral process.

A report for the OAS concluded, through statistical analysis, that “the pattern of votes, particularly in turnout rates, is suspicious,” and the proposition the National Party won the election legitimately, was rejected by the authors of the report.

***

Nasralla and the opposition alliance initially refused to recognize the results. The spokesman for the coalition, Rodolfo Pastor told Al Jazeera “our reaction is rejection and to call on the people to mobilize to make very clear that we will not accept the imposition of what the tribunal has said,” adding “if they [TSE] seek to impose Juan Orlando Hernández through this unilateral declaration, obviously a period of crisis and popular mobilization will follow.”

The United States recognized Hernández as the winner, and acknowledged “irregularities identified by the OAS and the EU election observation missions,” adding “strong reactions from Hondurans across the political spectrum underscore the need for a robust dialogue.”

Nasralla admitted defeat, with the U.S. recognition of Hernández, saying, “the situation is practically decided…I no longer have anything to do in politics, but the people, which are 80 percent in my favor, will continue the fight.” In a televised address, Hernández called for “peace, harmony and prosperity,” and as “a citizen and president-elect of all Hondurans, I humbly accept the will of the Honduran people.”

The U.S. support of Hernández has fueled the allegations of electoral fraud, as State Department officials allegedly pressured the opposition to stop protests. Nasralla claimed he was powerless in preventing such protests: “What I in my personal capacity as a comfortable person may be asking for, that is one thing… but another is what the mass of 6 million poor people want, and that is something I cannot impede — that the people will go to the streets.”

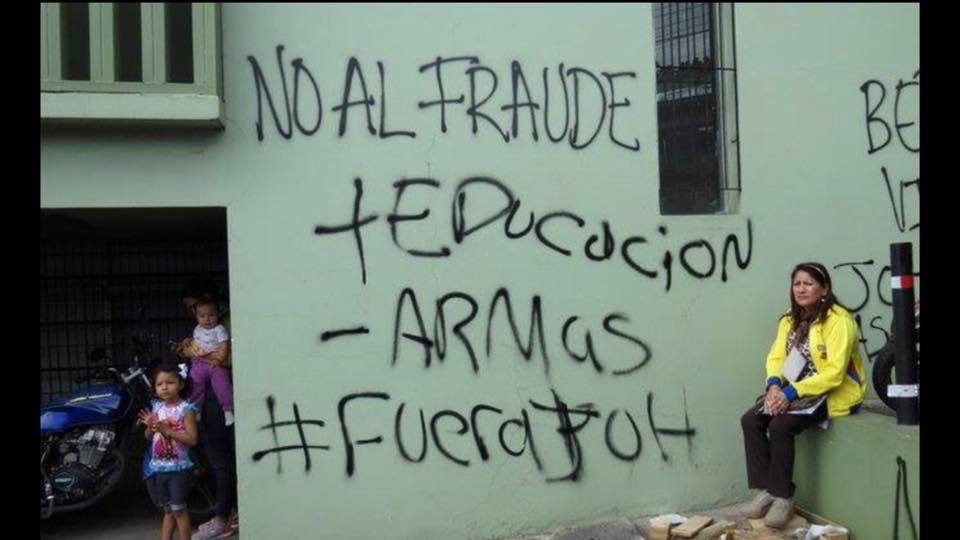

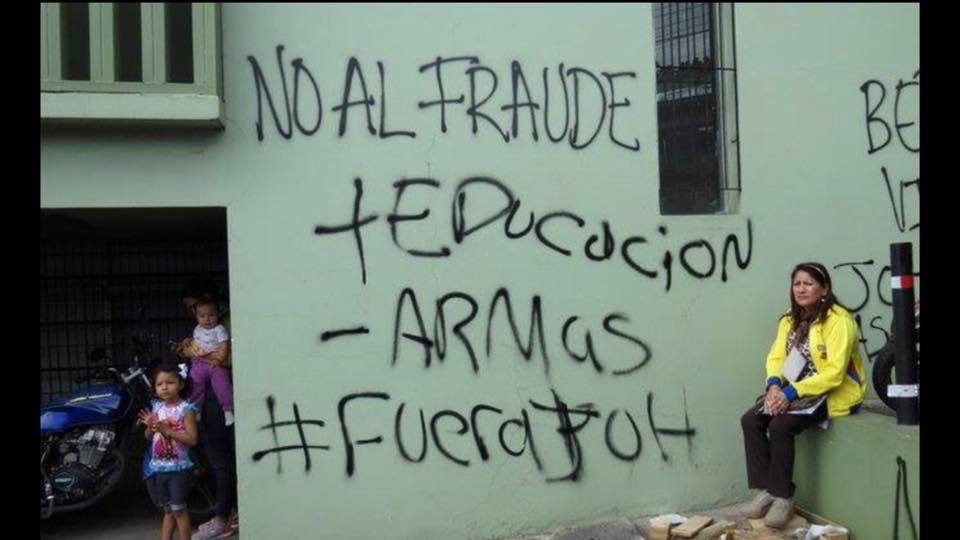

The claim, that the election was “stolen,” became a primary factor in opposition protests. The message, based on allegations of corruption, much of which was funded by the United States, has cemented a basic mistrust for Hernández by the people of Honduras.

Support has come, not only from the United States, but, according to a report from The Guardian, the United Kingdom sold Honduras £ 300,000 ($419,000) worth of telecommunications interception equipment, used to “intercept, monitor and track emails, mobile phones, and online messaging services such as WhatsApp.”

Amnesty International has claimed that the Honduran government has used these “dangerous and illegal tactics to silence any dissenting voices in the aftermath of one of the country’s worst political crisis in a decade…”

The government has deployed U.S. trained forces against protesters, and installed a curfew that was denounced by numerous human rights organizations. Security forces enforced the curfew with brutal force, as 200 people were arrested, and another 20 were injured.

Activists alleged violent intimidation tactics used by security forces, with 35 protestors killed by such forces since the November 26 election. The conflict has continued, as Hernández’s inauguration approached on January 27. Security forces clashed with protesters, as opposition leaders refuse to accept Hernández’s “mandate.”

“We have to stay in the streets,” said Manuel Zelaya, the former president of Honduras removed from office in a 2009 coup, “if they move us from one spot, we have to move to another. We need to be permanently mobilized to keep up the pressure and prevent the dictator from installing himself.”

***

The events that followed the contentious election act as a reminder that the events that occurred in 2009 hold a continuous influence on the Honduran political landscape. The by-product of Zelaya’s proposed non-binding constitutional referendum, the political crisis in Honduras has shown little signs of fading.

The United Nations condemned the coup, and diplomatic cables from former U.S. Ambassador to Honduras Hugo Llorens identified the events as such, stating: “The Embassy perspective is that there is no doubt that the military, Supreme Court, and National Congress conspired on 28th June in what constituted an illegal and unconstitutional coup against the Executive Branch…”

June 29, 2009 in Honduras (Yamil Gonzales)

The White House, and the administration of former President Barack Obama, had called what transpired “illegal.” It represented a problem for the Obama administration, and inaction allowed for the issues that caused the coup to ferment. In 2015, the issue that prompted Zelaya’s removal, the non-binding referendum that opponents saw as a power grab, was ruled constitutional.

Several human rights groups, such as Human Rights Watch, reference several instances of human rights violations committed by officials of the government and security forces. The Human Rights Watch report cites blatant police abuses and corruption, and attacks on journalists and human rights activists.

Eight years later, Hernández has solidified power, as the main components of the government, the judiciary and the electoral commission appease the president. Honduras, according to The Economist, ranks 92nd out of 113 countries on the measure of constraints on government powers.

Recommendations that called for new elections, from the OAS, and from Human Rights Watch, which requested that “Honduran authorities…take action to ensure the credibility of the country’s general election,” were unheard. Washington’s blessing, the tendency of the United States to ignore apparent electoral fraud, spoke volumes, even as numerous analysts claimed the election was “illegitimate.”

It has prompted serious questions as to the state of politics in Honduras, and of course, by extension the role of the United States. An analysis from Foreign Affairs recounted a “long genesis,” whose solution lies in remedying the “underlying problems of democratic institutional order and social inequality.”

The re-election of Hernández has allowed for continued dominance by the ruling National Party, however, the administration of Mr. Hernández does not hold a mandate. Hernández was expected to win the highly contentious election by 15 points, a result of a 56 percent approval rating. However, there is a deep-seeded mistrust in government.

Juan Orlando Hernández, president of Honduras. Credit: Daniel Cima/CIDH (Source: Flickr)

Sofía Martínez Fernández wrote for the International Crisis Group that “doubts over the probity of the electoral process reflect broader concerns as to the increasing power of the executive branch.” The inauguration of Hernández, held on January 27, did not assuage fears of further corruption, and other abuses of power.

The founder of the Committee of Relatives of the Disappeared (COFADEH), Bertha Oliva, summarized the situation in Honduras: “I’m obliged by my position to be positive, I’m here to raise hopes and be positive, but I can’t. We are in an undeclared civil war, where we’ve lost the hard-gotten gains of decades of campaigns, we’ve lost it.”

***

Nathaniel Santos Hernández is a graduate of the University of Maine, Orono, with a degree in Anthropology. You can follow him on Twitter @saint_nate12.