By Eliván Martínez Mercado | Center for Investigative Journalism

When Puerto Rico governor Ricardo Rosselló announced in January his intent to privatize the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA), he put a “For sale” sign on a public corporation that has already endured a failed and costly privatization fever during the administration of former Governor Luis Fortuño, also of the New Progressive Party.

After walking through the photovoltaic panels of the AES Ilumina solar farm in Guayama, which opened in 2012 as one of the largest in the Caribbean, Fortuño told the media about his new philosophy for producing energy with sun and wind: “This energy diversification strategy has as its primary purpose to lower the cost of power in the future and protect our environment.”

None of the objectives were met.

Out of the 60 projects contracted under the Fortuño administration, 11 became operational. Most sell power to PREPA at a cost between 18 and 20 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh), practically the same cost offered by the public corporation to consumers nowadays.

Former Governor Luis Fortuño at the inauguration of AES Ilumina in Guayama on October 8, 2012. (Photo courtesy of La Fortaleza)

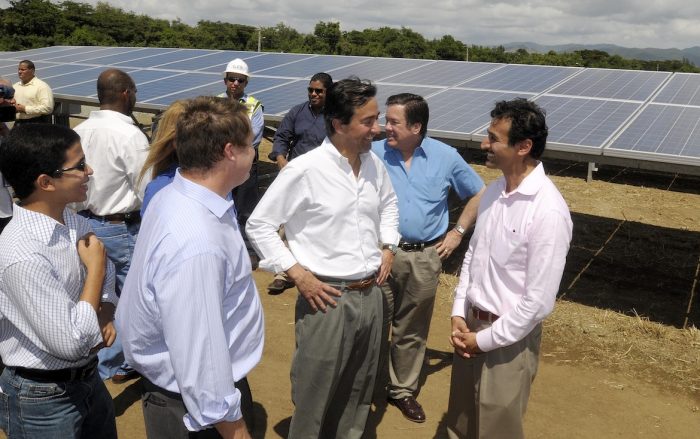

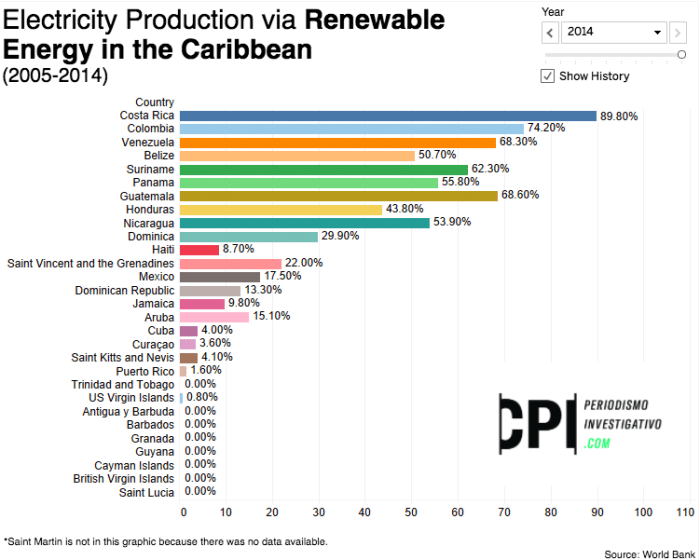

By only producing 2% of its energy from renewable sources, Puerto Rico is among the nations and territories of the Caribbean basin most dependent on such fossil fuels as oil, coal and natural gas, according to World Bank data. These fossil fuels not only pollute, but also emit greenhouse gases that accelerate global warming.

The following chart shows 2014 electricity production via renewable energy in the Caribbean. To see the entire history from 2005-2014, click here.

Fortuño’s privatizing push had a strong additional motivation: to spend, before time ran out to do so, the $7 billion in federal funds under the Recovery & Reinvestment Act, better known as ARRA funds, which in 2009 had been allocated by then President Barack Obama for purposes such as infrastructure.

So much pressure was exerted by the Governor’s Office in the decision-making circle of PREPA to achieve these renewable energy projects, that the Puerto Rico Department of Justice (DJ) described it as an undue interference and determined it was a “flawed” process, according to an agency document to which the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI) had access. The process, without contracting guidelines nor a negotiating committee, was so hurried that the government approved projects that exceeded the energy capacity that PREPA could integrate, pledging to pay for more than what the Puerto Rico’s power grid could use, in “a clear waste of public funds.”

Former governor Fortuño was not available for an interview on the matter.

Now, when Rosselló seeks to impose a ceiling of 20 cents per kWh, these renewable energy projects will take center stage during the negotiations that PREPA plans to undertake with private generators to lower their rates, as dictated by the Fiscal Plan submitted by the government to the Fiscal Control Board. Out of the 13 companies that currently sell power to PREPA, 11 are sun, wind and landfill gas. The remaining two are EcoEléctrica, which produces energy with natural gas in Peñuelas, and the AES Puerto Rico coal plant in Guayama.

A 2009 executive order by Gov. Fortuño and Act 82 of 2010 mandated the country to switch to renewables in order to deal with the volatility of oil prices. But the Windmar Renewable Energy solar panel plant, in the municipality of Ponce, turned out to be one of the most expensive projects selling energy to PREPA, charging 20 cents per kWh.

Windmar belongs to Víctor González Barahona, an entrepreneur who has managed to position himself in the residential, commercial and governmental renewable industry. Besides the Fortuño projects, the company has placed solar panels in a dozen facilities of the Aqueduct & Sewer Authority, including the treatment plants on the islands of Vieques and Culebra.

Windmar sells photovoltaic systems to residences in Puerto Rico and the state of Florida and also installs solar panels rented by Sunnova, the Texas corporation that dominates the residential renewable market on the island and is being probed by the island’s Energy Commission for overbilling and offering equipment that stopped working after the destruction caused by Hurricane María.

The company entered the renewables group in a hurry: “The contract was made without permits. When the businessman heard Gov. Fortuño say that he was going to move to renewable energies, he challenged him to connect his project to the grid because PREPA didn’t wanted to do it. Fortuño accepted it, signed it and approved it the next day. It is an example of how things should not be done,” said Juan Alicea, a former PREPA executive director who renegotiated contracts and stopped renewable projects when he took over the public corporation in 2013.

González Barahona has another project in Ponce, Windmar Vista Alegre, which sells energy to PREPA at 19 cents per KWh. “Nobody has told me that they want to lower the price,” González said about the two Windmar facilities that sell power to the public corporation.

The company proposed another five renewable projects that are among the group of those that failed to materialize, such as a wind farm in the municipality of Guayanilla, that lacked permits and intended to build on a property with archaeological sites. The company had sought to develop utility-scale projects since 2002, before Gov. Fortuño, during the administration of former Gov. Sila M. Calderón.

“One of Fortuño’s Biggest Mistakes”

PREPA was already in the middle of a fiscal crisis and lacked the money to develop new infrastructure when it looked for private investors with whom to sign the energy purchase contracts, namely Power Purchase and Operating Agreements (or PPOAs). The cost of the energy that PREPA was selling had skyrocketed to 30 cents per kWh. Faced with high oil costs, Fortuño’s projects offered rates that seemed competitive in 2012. But in 2016, it was evident they were no longer viable: as the cost of oil went down, PREPA could sell electricity at 17 cents per kWh, cheaper than projects such as Windmar.

Nine of the 11 renewable plants have a rate escalator —which implies that prices rise annually between 1% and 2%— as well as 20-year contracts. This guarantees that the rates go up, doing away with the alleged expectation to lower energy costs.

Moreover, nine of the 11 contracts included about 3 cents in renewable energy credits, or RECs (Renewable Energy Certificates), which are added to the cost of each kWh. These credits can be sold by a company that generates clean energy to another company or utility that, because of its use of dirty energy sources, needs to increase its score in environmental compliance.

The industry, in general, creates a market and self-regulates its prices, explained Efraín O’Neill, an energy systems researcher at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus. But in the case of Fortuño’s projects, PREPA fixed the price. “PREPA did not have to go into that of setting prices; it betrayed its fiduciary duty to the country, because the developer must fight for those RECs in the market, but PREPA gave it to them automatically,” O’Neill told the CPI.

The kWh costs of solar projects around the world, which in 2012 fluctuated from 20 cents to 37 cents per kWh, have dropped dramatically to 1 cent to 3 cents per kWh, demonstrating the important switch in the industry toward cost reduction and that Fortuño’s project prices are now obsolete, according to data of the Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century, a Paris-based organization that brings together the business, government and nonprofit sectors. As for wind energy projects, their cost fluctuated from 5 cents and 17 cents per kWh, but nowadays average 10 cents per kWh. Pattern Energy, the windmills company that operates in the municipality of Santa Isabel, today invoices PREPA at 16 cents per kWh.

Pattern Energy windmills are located in Santa Isabel. (Photo by Leandro Fabrizi Ríos | Center for Investigative Journalism)

“One of Fortuño’s biggest mistakes was those renewable projects,” said Francisco Rullán, executive director of the State Office of Public Energy Policy (OEPPE by its Spanish acronym), an entity that advises the commonwealth’s Executive branch. “If the issue was the price of energy in Puerto Rico, why didn’t the price go down? The reference price that the renewables gave was exaggerated. We have to learn from these mistakes to not repeat them,” Rullán told the CPI.

The request for an interview with Fortuño made by the CPI, which was not responded, was made through his spokeswoman, Michelle Cuevas. The lawyer and former governor works at the multinational firm Steptoe & Johnson, from where he has lobbied and intervened in energy projects that began during his administration, such as the plan to bring natural gas to the Aguirre power plant in Salinas and the Energy Answers incinerator in Arecibo.

The Puerto Rico government won’t cancel any of the 11 renewable projects that are already in operation, but will seek to lower their rates because they are considered too high, Rullán said. “Obviously we always have the good faith that it can be done without litigation. It will be renegotiated but without discouraging other renewable energy projects,” he explained. “Simply to create the awareness that there must be private investment, or much more private investment in renewable energy, from utility scale to the distribution of energy in homes, but not at an exorbitant price, at the expense of Puerto Ricans, who are the ones that are going to pay for this.”

Obed Santos, manager of AES Illumina, said the company won’t renegotiate a better rate. “I don’t have a solution to the problem. Because there is a contract that would be breached,” he stated. “There is an established investment already here, a financial model with that sale price. Changing that rate would do a lot of harm to the economic model of this project,” added Santos, who assured that AES spent $100 million in the solar plant.

AES was one of the first to sign a PPOA during the Fortuño administration, and built its facilities on 138 cuerdas (roughly 134 acres) adjacent to the site of its sister company, AES Puerto Rico, which produces energy with coal and has deposited ashes throughout the island for more than a decade. The federal government fined AES Puerto Rico on one occasion for contaminating wetland areas. AES’ photovoltaic project charges PREPA about 20 cents per kWh and 3.5 cents are included in the rate as payment for the renewable energy credits, or RECs.

Obed Santos, AES Ilumina manager (Photo by Cristina Martínez Mattei | Center for Investigative Journalism)

“The advantage of this energy is that I can predict the price in the next 20 years, unlike oil, which can go up again. We are aware that building this same plant today can be done at a better price, but this one already has a debt, because it was made with the prices of 2011, when solar panels cost three times more than what they cost today,” Santos said.

In a similar way, González Barahona, the Windmar executive, said: “Given the current conditions of the costs of renewable equipment, depending on the requirements placed on us by the government, a better price can be given,” he said in reference to the five projects he has on the pipeline. “Prices are given according to the context of the moment. In 2018, the prices of renewable energy are very, very different.”

Two projects signed under Fortuño offer the most competitive rates: those of Landfill Gas Technologies in Fajardo and Toa Baja. They sell energy at 10 cents per kWh. They are the only ones of the projects built that don’t have annual rate escalators or payment for renewable energy credits. Yet these plants generate energy using landfill gas. They depend on receiving trash in order to work, which is not ideal, according to Dr. Cecilio Ortiz, from the National Institute of Island Energy and Sustainability, a group of academics from the University of Puerto Rico who carry out investigations to solve the country’s energy problems. “To maintain the operation of these garbage plants you need a culture of waste,” he noted.

The main objective of renewables worldwide is not to lower costs but to produce clean energy. One pending task of Puerto Rico is to use renewables to meet the mercury and air toxics standards, known as MATS, imposed by the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

Act 82 mandates Puerto Rico to generate 12% of its energy with renewable sources between 2015 and 2019. These are goals that less than one year before the deadline, are not even on the horizon. Countries such as Costa Rica are fully energized with renewable sources, mainly with hydroelectric plants, which take advantage of the energy of the rivers.

On its 2% renewable figure, PREPA doesn’t include the production of hydroelectric plants that were already in operation, because Act 82 of 2010 sought the government to focus on new plants. Puerto Rico has 21 hydroelectric units in 11 points across the island, yet these account for less than 1% of all the energy produced in the country, according to the Puerto Rico Energy Commission. In the middle of the last century, hydroelectric plants generated almost half of all the energy consumed on the island, but the government left them in abandonment while giving prominence to oil, confirmed José Maeso, former executive director of OEPPE.

Solar panels of AES Ilumina in Guayama (Photo by Cristina Martínez Mattei | Center for Investigative Journalism)

“Absence of Good Faith of the Contractors”

The beginning of generation with private renewable projects —the 11 online and the 49 that were never built— is marked by an illegitimate process: PREPA failed to open to competition by means of requests for proposals to ensure that it would receive the best offers. The Governor’s Office, without expertise to select the projects, negotiated contracts and then refer them to PREPA. The Fortuño administration thus violated the autonomy of the public corporation, according to the “confidential and privileged” brief by former Justice Secretary Luis Sánchez Betances, to which the CPI had access. The lawyer was appointed by former governor Alejandro García Padilla of the Popular Democratic Party, the main opposition party to Fortuño’s New Progressive Party.

Officials at the governor’s office showed “ignorance and little control over the matter of the contracts, which led them to accept onerous terms,” while “the absence of good faith by the companies becomes evident when taking advantage of the situation,” according to the Justice Department document reviewed by the CPI.

In the same document, Justice told Juan Alicea, then executive director of PREPA, that he had legal basis to cancel the contracts, because the public corporation was forced to accept terms negotiated by the Governor’s Office and for “absence of good faith of the contractors,” who failed to quote based on fair and reasonable market prices.

Corretjer LLC, a law firm, issued two legal opinions in 2013 and 2016 to the PREPA executive directors noting that the Fortuño administration declared an energy emergency without a real need for these projects, since PREPA was generating energy in excess of the island’s demand. It recommended to the public corporation an intermediate solution to the leonine contracts: cancel those that were noncompliant for not having been launched on the established dates, and maintain or renegotiate those that were already advanced. That is why PREPA stayed with 11 of these projects.

The 49 renewable projects of the Fortuño administration that were not built remained in a limbo amid attempts to renegotiate terms and arm-wrestling with the public corporation. The subsequent administrations of García Padilla and Rosselló have slowed this group of companies mainly because they had not managed to obtain permits and the transmission and distribution system is not prepared to receive all the energy they could generate if they were built.

Today, the Blue Beetle company is suing the public corporation for $110 million, arguing that the PPOA offered by PREPA to generate 20 megawatts in Barceloneta was induced by “bad faith” and “fraudulent” intentions. The company alleges that PREPA claimed to have cash flow to maintain a good score before credit-rating agencies, only to go bankrupt. Blue Beetle also claims that PREPA caused damages to investors of the solar initiative by canceling the project that, supposedly, was going to lower the energy costs of the public corporation. However, Blue Beetle offered PREPA energy that, with the annual 2% rate escalator, would have reached 16 cents per kWh after 25 years of the contract. The rate includes renewable energy credits that are automatically paid by the government for producing green energy.

Among those projects that weren’t built, the Rosselló administration is in the process of negotiating with at least 18 of them. “The negotiation will not be the same as the one they had previously. 19 cents per kWh is not a good deal,” Rullán insisted. He argues that, according to current market prices, an acceptable price would be 10 cents per kWh.

The island’s Fiscal Control Board (FCB), imposed and appointed by the federal government to decide quickly over what it considers to be critical projects for infrastructure development, opened a public comment process on 11 proposals. Among these, five were projects contracted by the Fortuño administration that had failed to prosper. They are the Blue Beetle solar farm in Barceloneta, the same company that is now suing PREPA; Vega Serena and M Solar, both in Vega Baja; and Solaner Puerto Rico One, in Cabo Rojo. There is also the Arecibo Resource Recovery Facility, better known as the controversial Energy Answers project, which PREPA classified as renewable under the Fortuño administration despite being a garbage incinerator.

After Rosselló said he didn’t support the Energy Answers project, the corporation withdrew from the list of critical projects, although the FCB leaves the door open for the company to propose the incinerator in the future, according to the information on its website. Energy Answers proposed to charge 14 cents per kWh, including the payment of RECS, through a 30-year contract, the company told the CIJ in a written statement.

The Hurry to Spend ARRA Funds Led to Failed Contracts

The Puerto Rico Department of Justice investigated the alleged undue interference by the Governor’s Office in renewable projects. It was an irregular process in which most of the contracts were hastily signed during the last days of the Fortuño administration, mainly in December 2012, after the governor had lost his reelection bid. But prosecutors failed to prove that corruption was at the heart of the process.

José Pérez Canabal, an engineer responsible for promoting more than half of the contracts during his tenure as vice president of PREPA’s Governing Board between May 2011 and June 2012, was charged in two separate criminal cases for alleged conflicts of interest and for allegedly committing fraud to favor the company Tropical Solar Farm. He came out successful as neither case prospered.

The privatizing drive of that time was influenced by factors that were not exclusively a planning process to move the country to the next level in its energy development. Pérez Canabal alleged, in an interview with the CIJ, that the Fortuño administration wanted to take advantage of the federal money from the so-called ARRA funds, for which they had until December 2011. “We were against the clock,” he said. That turned the process into a fast-track operation. The government was also trying, according to the engineer, to meet the 12% renewable energy goal.

“As a result of this, the world was called upon,” said Pérez Canabal, referring to the search for companies in and outside of Puerto Rico to focus on Fortuño’s energy philosophy. PREPA’s governing board imposed three requirements for interested companies: owning or having control over the land where the projects were to be built, having financial capacity and that the proposed infrastructure was close to a point of connection with PREPA.

Then, the fever for these private projects collided with the change of government, in which the administration of Juan Alicea at PREPA alleged that the system wasn’t prepared to receive all the 1,560 megawatts that the renewables were going to generate. The public corporation used a study of the German industrial conglomerate Siemens, delivered to PREPA in February 2014 and which holds that the public corporation could only receive 800 megawatts.

And with the fever of these projects, along came the high costs. “Today we have seen that the price of oil dropped but when it was $112 a barrel and the cost of PREPA was 28 cents per kWh, what the renewables offered was wonderful. If you evaluate the projects with today’s parameters, you reach another conclusion, but with hindsight, those prices are what you saw at that time, it was the price of renewables worldwide,” Pérez Canabal said.

Juan Rosario, the public interest representative at PREPA’s governing board from June 2012 to June 2015, affirms that the same contract that was signed in 2012 can now be obtained 50% cheaper, because the technology changed. “Fortuño’s projects are a rip-off. Instead of pushing the development of renewable energy, what they do is block it when you are tied to those prices, while in the world it is selling at 2.8 cents per kWh. And these companies say that we pay ten times more because PREPA signed a bad contract. Renewable technologies are changing so fast that to consider taking those 60 contracts at that price was crazy.”

Comments to emartinez@periodismoinvestigativo.com