Originally published at the author’s own page.

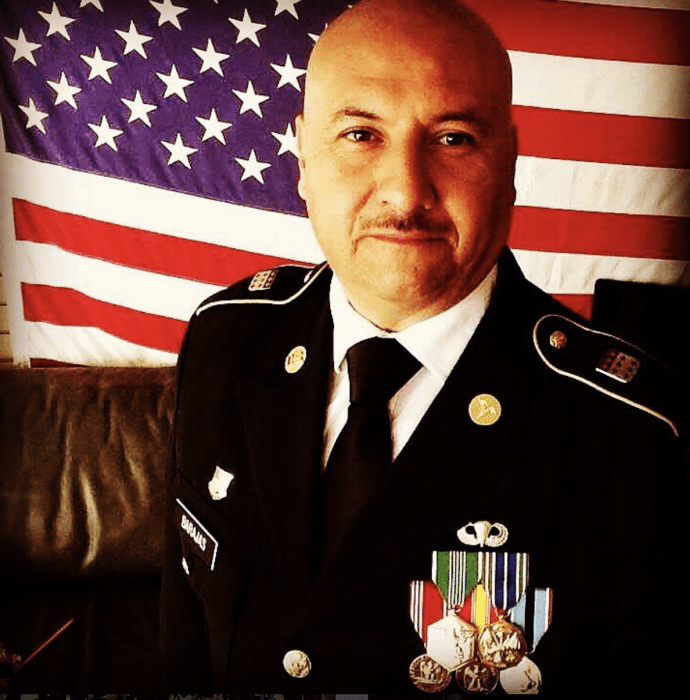

TIJUANA, MEXICO — In a small room full of cameras, an American flag pinned on the wall becomes the backdrop of every shot. Hector Barajas sits on a leather couch placed against that wall. He is about to read an immigration decision that could decide his future to either return to the U.S. or stay in Mexico. Barajas is part of an ever-growing population of U.S. deportees with one exception—he is a military veteran.

Instagram photo @Deportedveteran

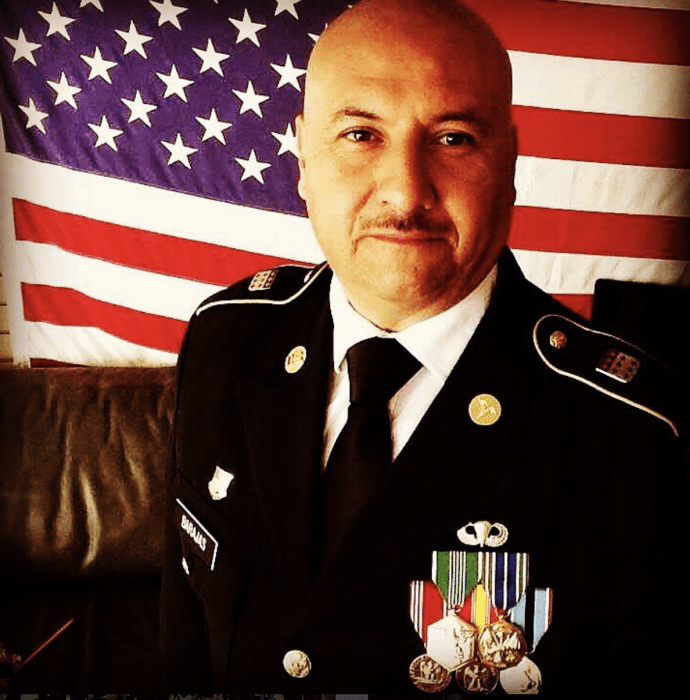

“Deported veterans are people who served in the armed forces all the way from the Vietnam War era to the guys who are coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan” says Barajas, founder and director of the Deported Veterans Support House (DVSH), an organization set to provide assistance to U.S. military serviceman who have been deported to Mexico in the border city of Tijuana, Mexico.

“The most important thing that we do is housing. We make sure they get somewhere to sleep until they get their life situated” Barajas says about deported veterans. The recourses center also helps the deported veterans obtain their Veterans Affairs (VA) benefits, compensation pensions, legal services, physical, and mental health resources.

Instagram photo @Deportedveteran

There are two “Bunkers” (as the DVSH centers are commonly called) in Mexico, but the organization is planning to open more Bunkers wherever there are large populations of deported veterans around the world. Barajas is currently in talks with deported veterans in the Dominican Republic and Jamaica, where he will be assisting other veterans to open their own “Bunker” in the near future. He has identified 350 deported veterans around the world and 60 deported veterans in Tijuana and Juárez, Mexico—the second location of the Mexican Bunkers.

According to Barajas, DVSH members are made of once legal residents and undocumented Vietnam War veterans who were drafted during the Vietnam War. It also includes veterans such as himself who served the U.S. in later years.

Barajas came to the U.S. at the age of 7 years old and settled in Compton, California, with his family. As a teenager, Barajas was granted a permanent residency card. Right after turning 17 years old, he enlisted in the military and at 18 years old, Barajas joined the Army and served with the 82nd Airborne Division. He served the military for two terms, from 1995 to 2001. He became a wartime veteran due to his services from the aftermath of 9/11.

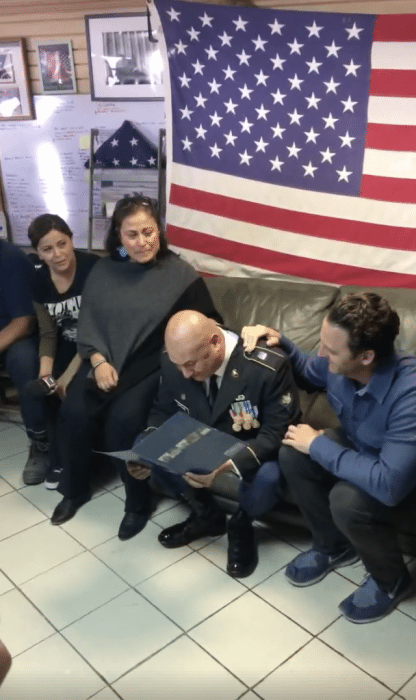

Instagram photo @Deportedveteran

After his military service, Barajas served a 2-year prison sentence for unlawfully discharging a firearm in 2001. In 2004, Barajas was deported back to Mexico for the first time. He returned to the U.S. and was deported a second time in 2010.

“I went through the whole deportation proceeding and when I was getting deported I thought I was the only person that was going through this and then over the years through my advocacy work I’ve identified hundreds of veterans being deported around the world,” says Barajas when talking about why he got involved with the organization. “I feel committed and somebody needs to do something about it.”

After serving a prison sentence Barajas was picked up by immigration. “I thought I was going to be released initially,” Barajas notes. He was eventually put in deportation proceedings and was sent from California to Eloy, an immigration detention center in Arizona. That’s when he was able to let his family know he was being deported. “I thought that as soon as they would find out I was a veteran I was going to be released but being a veteran carries no weight on being deported under the current laws.”

According to a 2017 Washington Post article, “500,000 foreign-born U.S. veterans lived in the country in 2016. Since October 2001, more than 100,000 military members have become naturalized citizens.” They credited these numbers to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and the Migration Policy Institute.

There is a misconception that veterans become U.S. citizens automatically after their military services according to Barajas. “We have been drafting undocumented immigrants since the Civil War,” Barajas says. While there is a path to citizenship in the military, Barajas points to the lack of information from the military about such proceedings and initiative from individuals who qualify for these benefits. “Sometimes you get deployed to Afghanistan and the last thing on your mind is trying to figure out your citizenship while you are trying to survive and stay alive,” he continues. “It’s kind of hard to be thinking about your N-400, the application for U.S. citizenship, while dodging bullets.”

Many of the deported veterans Barajas helps fell under the wrong assumption that they too would not be deported due to their military service, according to Barajas. “Some thought that they were citizens because of their recruiters,” says Barajas. “So what happens when you come home from the military if you go through some rough time? Not only do you serve a prison sentence, but then you are picked by immigration,” says Barajas.

According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, about 11 to 20 percent of veterans will suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or PTSD.

“I see a lot of mental health issues, not just because of deportation but because of the military service, but deportation also affects you as well,” he adds.

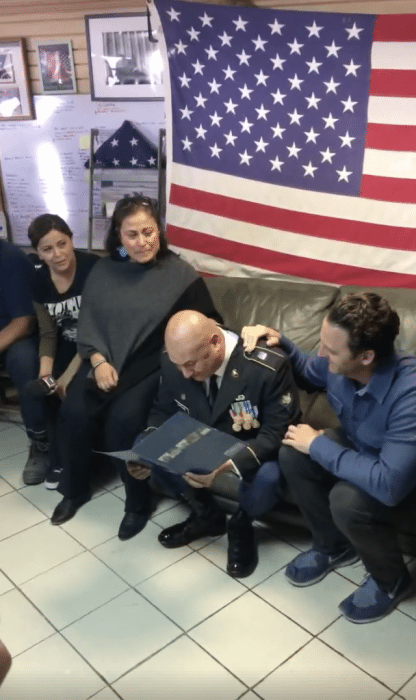

Back at the Tijuana Bunker, Barajas opens a blue a folder that contains his U.S. immigration decision. Stumbling on his words, he shouts, “Hallelujah! Mom, I am coming home mom!” He then turns to other deported veterans in the room and says, “I am not stopping for any of you guys, you guys know my commitment.”

Facebook Photo @Hector.Barajas2

Barajas has become the first deported veteran with Mexican nationality to come back to the U.S. as a citizen. He is to be sworn in as a U.S. citizen on April 13 in San Diego, California.

Editor’s Note: Barajas was a guest of Latino Rebels Radio in 2015.

***

Juan Diego Ramírez is the author of Corre La Voz. He tweets from @juandr47.