By Eliván Martínez Mercado

Spanish version here.

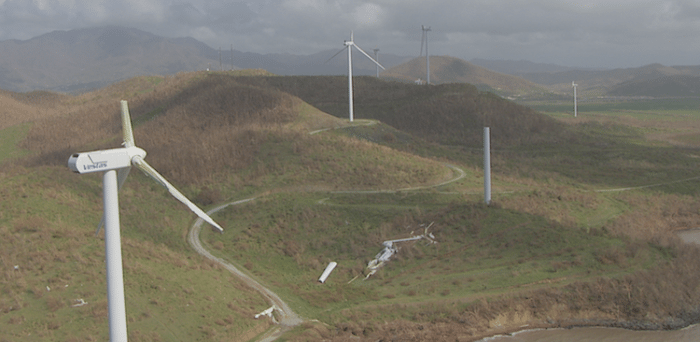

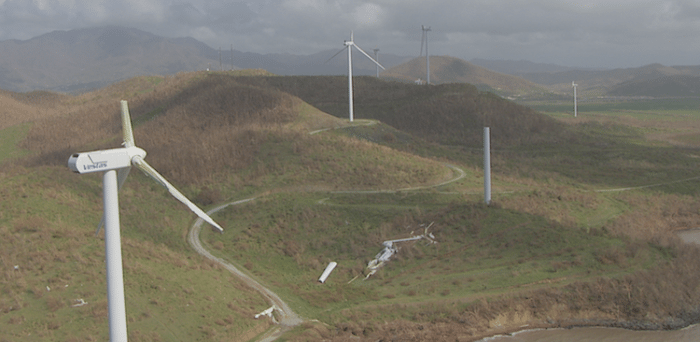

Zory Pérez went out to look for her parents after Hurricane María, and saw that the blades of the wind turbines erected on the agricultural plains of the town of Santa Isabel were halted. Despite having survived gusts of 155 miles per hour, the devices looked like useless figures, symbols of the lack of adaptation of Puerto Rico’s electrical system to climate change.

Time ran against her mother’s health, who needed to turn on the refrigerator to safe-keep the insulin with which she treats her diabetes. “Everyone in town asked the same thing,” Pérez said, “‘Why don’t they turn on the wind turbines, why don’t they turn on the wind turbines?’” Ten days after the atmospheric phenomenon, still without electricity, her parents had to leave the island.

To the west of Puerto Rico, the town of Mayagüez had electricity downtown and two fully energized hospitals only four days after the hurricane. In the marquee of the theater, located steps from the square, a message gave testimony of the situation: “Mayagüez is up and standing, Puerto Rico rises.”

Yagüez Theater in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico (Photo by @paomaria33 | Facebook/OrgulloPUR)

The municipality is the only one on the island that has a permanent mini power grid that can operate autonomously during extreme events. A gas generating plant, located in the port area, sends electricity through underground lines to the urban center. From this transmission network, cables are connected to poles that distribute energy to homes, businesses and public areas. By generating the energy near the consumption points, the network’s distribution lines are repaired faster in case an extreme event damages them, while the buried transmission lines are more difficult to destroy by the winds. These features make the system suitable for our current climate change scenario which promises to bring more frequent and intense hurricanes.

Hydro-Gas Power Plant in Mayagüez, from where key areas of the town were energized after the hurricane. (Photo by Jimmy Crespo | Center for Investigative Journalism)

At the request of Mayagüez Mayor José Guillermo Rodríguez, the system was designed with the collaboration of the municipal administration, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) and the central government 20 years ago, after Hurricane Georges left the town in darkness. At that time, there was no talk of small networks or resilience, but the need showed them the model. And, when Maria arrived, it worked.

A mini power grid allows the system to generate, transmit and distribute electricity near the point of consumption, in urban areas and towns. While microgrids follow a model on an even smaller scale connecting one house to another. These systems, as well as the installation of energy storage centers, had been until then mere proposals by experts who talked about improving the electrical system to avoid disasters in the future. Until the premonitions of what could happen came to be after hurricane Maria caused the second largest blackout in the history of the world, as economic research firm Rhodium Group documented in 2018.

These measures of resilience, the small networks and energy storage with batteries, were contemplated by PREPA’s fiscal plan submitted on March 21, 2018 by Gov. Ricardo Rosselló to the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, the federal entity appointed by the U.S. Congress so that the Commonwealth pays its debt. That plan was amended in April 2018 by the Board, but kept those measures and was imposed on the agency.

The same is proposed by the Puerto Rico Energy Resiliency Working Group, formed by the federal, local, and State of New York governments, along with private organizations such as ConEdison, which was hired to support the restoration of the electrical system. They created a plan to build a system that can survive categories 4 and 5 hurricanes—the most extreme. All these entities claim that batteries and small electrical networks are the best way.

Tesla (owned by inventor Elon Musk), German company Sonnen, and Fluence (AES-Siemens), are in competition for the energy storage market in Puerto Rico. The first two have shown interest in participating in a call to install batteries to support an economic development project in the facilities of the former Roosevelt Roads Naval Base in the municipality of Ceiba, the State Office of Public Energy Policy (OEPPE) confirmed. Fluence is in talks with the Fiscal Control Board and PREPA to offer an industrial-level storage system, the company confirmed to the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, for Spanish acronym.) The development of energy storage infrastructure could represent a market with investments of more than $250 million in five years, according to the fiscal plan.

But the island is still far from moving into a resilient model. The governor has said that, given the slow arrival of the funds promised by the federal government for the reconstruction, the work done by PREPA and the U.S Army Corps of Engineers is limited to restoring the electrical system destroyed by the hurricane.

“Absent substantial federal funding for the rebuilding effort, the Energy Resiliency Working Group recommendations cannot be implemented,” Rosselló alleged in the plan he submitted to the Board.

To that it must be added that the governor and the U.S. Department of Energy seem to be at odds over who is tasked with designing a new electrical system. While Rosselló says that his proposal is contained in the bill to privatize PREPA, the federal energy agency is creating a new prototype: a model that will be tested in Puerto Rico with plans to being replicated in the U.S., Canada and Mexico, said Bruce J. Walker, representative of the Department of Energy, in a convention of the battery and storage sector that took place April 18-20 in Boston.

Bruce J. Walker, Deputy Secretary of Energy, Electricity, Distribution and Energy Reliability of the federal Department of Energy. (Photo by Lourdes Álvarez | Center for Investigative Journalism)

Although Rosselló is also promoting his bill to privatize PREPA as a possible solution to the problem, this alone does not solve it because it does not address the need for microgrids and distributed generation (with solar panels in homes and communities, for example,) a deficiency noted in a report by The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Nor does it contemplate storage systems. Some of these proposals have been promoted for the last 10 years by experts from the University of Puerto Rico’s National Institute of Island Energy and Sustainability (INESI, by its initials in Spanish.)

In the Don Alonso sector of Utuado, one of the so-called “pockets” without electricity, the CPI was able to observe PREPA brigades that were not bandaging, but putting on used bandages on the electrical system. One brigade, deep into the thicket between two mountains, carried a cable from one side to the other, pulling it with a rope, a job that helicopters used to do. Without materials, the workers collected old cables that had been thrown by the hurricane, trying to solve the problem for customers who have been without power for almost seven months after the hurricane.

On April 12, 2018, when a tree fell on the transmission line that runs from the Costa Sur power plant in Peñuelas, to Aguas Buenas and Bayamón, almost a million customers were left without electricity, as a warning of what may happen again. A similar event occurred on April 18, when a stateside company contracted to repair the electrical system knocked down the line connecting the AES generator in Guayama with Central Aguirre in Salinas, causing a general blackout. The next hurricane season begins in summer. The electrical system is still vulnerable.

Cars Ready to Start, But Have No Road

When the residents of Santa Isabel asked for the wind turbines to be turned on, the town’s mayor met with PREPA managers the day after the hurricane to find a way to bring energy to the town. After all, the wind farm has the capacity to power more than 28,000 residences and was there, steps away from many houses. The representatives of the public corporation told him no, that the system was not ready, said Alberto Toro, municipal security commissioner.

The private renewable generation facilities were slow to take action, because PREPA kept them on trial periods and did not authorize them to connect to the network, Francisco Rullán, executive director of the OEPPE, told the CPI. In part, the problem was due to the lack of energy storage systems that renewables need to provide generation stability.

In the absence of direct energy from the wind turbines to Santa Isabel, the town had to settle for waiting for power to return when the system was repaired from Costa Sur in Guayanilla, via a stretch of some 30 miles of cables. It took about three weeks after the hurricane for the urban center of Santa Isabel to start seeing lights, and until November 2017 to achieve at 90% of homes with power, with the remaining 10% being “pocket areas,” according to Toro.

The lack of resilience in Puerto Rico is largely due to the way PREPA conceptualized its electricity network. The main generators such as Costa Sur in Guayanilla, the Central Aguirre in Salinas, and the AES coal plant in Guayama, are located in the south, far from the metropolitan area, where 70% of electricity is consumed. They have to deliver energy from the south to the north of the island, passing through the mountainous area. Nine of the 11 solar, wind and landfill gas projects signed under former governor Luis Fortuño’s administration with the promise of improving the power system were also built mainly in the island’s southern and eastern flanks.

Fossil fuel generators (petroleum, coal and natural gas), as well as the renewable sources, were designed to connect to the public corporation’s centralized transmission and distribution system destroyed by the gusts. They are tied to an intricate nest of more than 33,000 miles of cables, according to PREPA. If they were placed side by side, they could go around the planet one-and-a-half times.

The windmills of the Punta Lima wind farm in Naguabo suffered from the winds of Hurricane María. (Photo by Geoambiente)

With the exception of the solar farm in Humacao and the wind farm in Naguabo, destroyed by the hurricane, all the renewable generation projects survived the gusts but stopped delivering electricity to the grid, said Lionel Orama, coordinator of INESI. “It’s like you have a lot of cars ready to start, accelerating, wasting energy, but they have no road to go to.”

It is true that winds of more than 200 miles per hour were certified in Puerto Rico during the hurricane, for which the utility poles and lines were not prepared. The poles, in addition, were overloaded with cables that have nothing to do with the electrical transmission and distribution system, such as cable TV and telephony lines. It is also true that if private generators had organized themselves in microgrids, they could have helped to avoid deaths, help the victims and try to start seeking normalcy in the midst of disaster, Daniel Aldrich, director of the Masters in Security and Resilience Studies at Northeastern University in Boston, told the CPI.

“Small networks are infrastructure that works as life-saving tools. They also give people confidence, it makes them feel more secure during an emergency,” Aldrich added.

“Resilience does not come from a single company or technology. It comes from the knowledge that local engineers have to make changes and repairs, combined with the technology of the companies that arrive and with the investments made by the companies and the banks to build the projects. The combination and interaction of all factors help resilience,” he said.

Mayagüez retailers give faith of that. In the first days when there was no power in the urban center, the Ricomini bakery was facing a swarm of people who came desperately to buy any available food. It was one of the few businesses open after the hurricane. “We were taking orders and billing by hand because the computers would go out. Since there were so many people, it was very hot, because the power plant was not enough to turn on the air conditioning. With so many people together, the work was difficult,” said Sylkia Carrero, employee of the bakery.

Receiving electricity from PREPA on the fourth day after María meant ending the need to get diesel to focus on other issues caused by the emergency, and avoid prolonged fuel expenses that could have jeopardized the economic viability of the business. “If it had happened to us as in other places in Puerto Rico, which are still without power, we might have had to close. But we are still here giving it our all. We remain one of the strongest businesses in the town,” said Luis Torres, from Siglo XX restaurant, near the square.

From the Mayagüez gas power plant, the same one that energizes the minigrid, a 38 kilowatt transmission line went to a substation in the same town, from where a cable was connected to deliver power to the Costa Sur power plant, which needs power to start. “The system’s recovery after the hurricane began in Mayagüez,” Orama said, emphasizing how small power grids can be used at the same time to interconnect with other systems and support each other.

Pattern Energy wind company was disconnected from the grid until November 30, 2017, and began to transmit power on February 14, 2018, almost five months after the hurricane, when they received PREPA’s approval, Rubén Rivera, who manages the company’s facilities, confirmed.

Why was this project implemented in the same centralized network? Shouldn’t it have been installed to withstand a hurricane? “I completely agree,” he said. “The way PREPA’s transmission system was before, it did not allow for that type of design. We deliver energy through the 115-kilowatt transmission network, which is how PREPA designed the system, but to connect with a line of 38 kilowatts or less, so they work as an island, in more localized spaces such as Santa Isabel and Coamo, it would be necessary to install additional equipment, but it is possible,” said Rivera.

He argued that PREPA has not yet proposed starting a plan to connect the project to a smaller network, nor have they approached him about a battery system that would allow for a solid operation or using an additional company that would provide energy storage service.

Tesla, Sonnen and Fluence Seek to Expand Their Footprint

When South African inventor and entrepreneur Elon Musk flirted with Rosselló on Twitter, by offering his company Tesla to help Puerto Rico after the hurricane, he entered the island’s energy scene in the absence of energy storage systems.

His company not only offers the famous Powerwall batteries that are used at residential and commercial levels, but storage equipment on an industrial scale, similar to the ones he already implemented last December in the Australian town of Jamestown, with the capacity to power more than 30,000 houses for one hour in case of a general blackout. Tesla wrote a letter to the Energy Commission of Puerto Rico, making its recommendations for the resilience of the energy system, as part of the request for comments from the energy regulator to run the microgrids.

German company Sonnen, which sells batteries for residences and businesses, such as those donated to a laundry equipped with solar panels in San Juan’s La Perla neighborhood and a community photovoltaic project in the Mariana neighborhood in Humacao, proposes to regionally interconnect this type of storage system to convert it into a kind of large battery that serves PREPA, said Adam Gentner, the company’s director of business development for Latin America.

There is a direct relationship between batteries, renewable sources and micro-grids, although none depends on the other to be implemented. All sun- and wind-based generating plants present a problem when reconfiguring them into smaller and independent networks. None of those installed in Puerto Rico have storage systems that allow them to operate autonomously, the OEPPE told the CPI. Batteries are important for solar installations because they can provide electricity at night, when the photovoltaic panels do not receive solar energy. They also stabilize the system when clouds cover solar panels during the day, or when the winds needed by the wind farms decrease. The storage equipment helps to load the network at times when demand increases at peak hours, as it tends to happen after 5pm when most people start getting home after work and turn on televisions, electric stoves and air conditioners.

Rosalina Abreu, president of the Educational and Communal Recreational Association of Mariana neighborhood in Humacao, an organization that uses Sonnen batteries together with their photovoltaic equipment. (Photo by Cristina Martínez | Center for Investigative Journalism)

The contracts signed by 11 renewable energy companies during the Fortuño Administration did not require batteries to fulfill that purpose.

With the exception of the Pattern projects, AES Ilumina in Guayama and Punta Lima in Naguabo —which were the first to sign contracts— the renewable projects were only required a minimum storage system so that generation downturns were not sudden and they would give PREPA time to put the combined cycle plants to work as an assist, the OEPPE confirmed.

“That’s when I submit, before María, the idea of regionalized battery banks in a proposal with the Authority for Public-Private Partnerships. We are waiting for them to authorize it,” Rullán said. “They would be separate projects from the Fortuño projects. Right now, they have a deficiency that they have to seek to resolve for themselves. I cannot force them to set up the system because the contract was prior to the public policy change. That is why I am proposing that regional battery banks be installed under new negotiations.”

The Future of the Network in the Face of Debt and the Lack of an Economic Plan

PREPA, the public corporation that maintains control over Puerto Rico’s entire electricity system, with the exception of a few homes and business that have off-the-grid systems, lacks the money to invest in critical infrastructure. It owes more than $9 billion to its bondholders and is in a bankruptcy process through Title III of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act, known as PROMESA. The law was passed by U.S. Congress in 2016 so that the island and its public corporations pay their debt. Before it went bankrupt, the public corporation had faced layoffs, cuts and decreases in equipment inventories, which limited its ability to respond to the hurricane. That said, the public corporation was prey to the most important environmental disaster in almost 100 years.

Microgrids, renewables, batteries, resilience. They are concepts and tools that Electrical Engineer Lionel Orama, one of INESI’s coordinators, considers may not be able to solve the island’s energy needs unless public energy policy is not considered beforehand.

“The solution has nothing to do with technology. We need to know what we want our energy system for, for what economic model and where it will be developed. Are we going to consume a lot or a little with that model? When we have those answers, then we can begin to combine technologies to achieve the system we want. You have to agree on an energy vision to decide how to get there.”

Rosselló’s project is about privatizing power generation and conducting a Public-Private Partnerships for the transmission and distribution infrastructure, without addressing the questions that Orama talks about. “We talk about privatization as the theory that markets will be opened, but we have private projects that are not resilient.”

Send comments to emartinez@periodismoinvestigativo.com

This story is part of the series ISLANDS ADRIFT, the result of the work of a dozen Caribbean journalists led by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CIJ) in Puerto Rico. The investigations were possible in part with the support of Ford Foundation, Para la Naturaleza, Miranda Foundation, Ángel Ramos Foundation and Open Society Foundations.