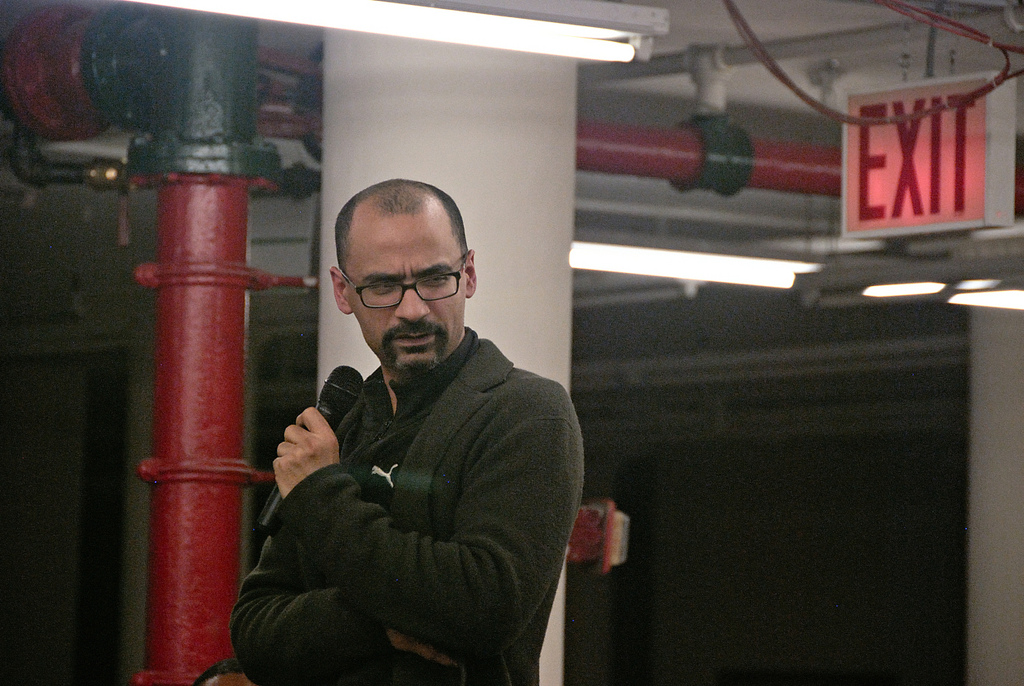

The recent revelations about Dominican-born writer Junot Díaz have exposed a side of Díaz that although known to many, had remained hidden.

That dual character in one of the most celebrated Latino writers reminded me of the 1996 film “Primal Fear,” in which actor Edward Norton compellingly portrayed a young man accused of brutally murdering a pedophile archbishop. Throughout most of the movie, we see Aaron Stampler, a shy, sensitive, kind young man. His lawyer (Richard Gere) believes Aaron’s crime can be explained and justified by the trauma he suffered as a victim of pedophilia. The audience believes it as well.

About halfway into the movie, we learn that Aaron also suffers from dissociative identity disorder —likely resulting from the sexual abuse he endured— and then we meet Roy, Aaron’s alter ego, a violent sociopath who proudly confesses having killed the priest. Because of his dual-personality disorder, Aaron receives a short sentence to a psychiatric facility. At the end of the movie, his lawyer realizes that his client has duped him by faking his dissociative disorder. Thinking that Aaron is the creator of aggressive Roy, Gere’s character tells him, “There never was a Roy.”

To which Roy replies, “There never was an Aaron.”

There never was a Junot Díaz.

From the moment his first book Drown surfaced, Díaz’s talent was praised as refreshing by many in the academic ruling class. His rise to fame in these circles was swift and far-reaching. Díaz became a superstar among undergraduates, graduate students, public, private and Ivy League colleges. Junot Diaz came to be known as the “cool” writer who was also deeply versed and could quote Shakespeare, Toni Morrison or the Notorious B.I.G. His fame was not limited to the identity politics circle. He was embraced by the establishment of the publishing world —a world that is predominantly white and male— and he quickly became The New Yorker’s “golden brown boy.”

His approval was sealed. He could cruise among the elite of the literary establishment with such ease that eventually the positive reception and acceptance culminated in a Pulitzer Prize and a MacArthur Genius grant.

When Díaz debuted his first collection of short stories, Latinx stories and authors were rare and Dominican literary presence in the United States was minimal. We only had Julia Álvarez, who many thought had lost her “accent” and did not mirror the “real” Dominican immigrant experience. So it was no surprise that many followed Díaz not only because they admired his talent, but also because his work revealed issues and experiences representative of an entire ethnic community.

His triumph felt our own. It felt as if his acceptance could open doors for other talented Latinx, even if Díaz was not the one holding the door open for them. True, the Latinx community adored him. But that adoration quickly turned into tacit disappointment when the academic rumor mill began to churn out rumors of Diaz’s condescending attitude and predatory behavior towards female students and young professors. Similarly disheartening were his “prima donna” antics. Local restaurants and college campus hotels did not seem to be up to his standards. Yet, very few dared to talk about Díaz’s actions lest they be accused of envy, resentment, or much worse, betrayal of one’s own.

But that is no longer the case. Latinx are no longer holding back and Díaz is back in the news.

The trend began with the courage shown by author Zinzi Clemmons, who fearlessly confronted Díaz at a writers’ festival in Australia. Clemmons publicly forced Díaz to reflect on the mistreatment she had endured by him when he kissed her against her will in the context of the sexual abuse he suffered as a child, which he recently detailed in an essay published in The New Yorker. In that article, Diaz acknowledges his misogynist behavior and admits that he has “hurt” women, but fails to tell us how. Which is why we need to fill in the blanks for him.

It hasn’t taken long for other women to follow Clemmons’ lead and come forward. Stories are surfacing from women who felt victim to Díaz’s sexual and verbal abuse. One exposé came from Karina Maria Cabreja. In her powerful account, Cabreja admits her difficulty to unmask Díaz’s disregard for women, particularly women of color. And after ignoring her mother’s advice to portray Mr. Díaz as “respectful,” she declared: “Junot Díaz was not respectful to me. He was condescending, sarcastic and mean; that’s the truth.”

Yet Díaz has been constructed as a sensitive, progressive thinker, who denounces discriminatory practices. For instance, he has been very vocal in decrying the state-sponsored discrimination against Haitians and people of Haitian descent in the Dominican Republic, even while it has earned him vicious attacks, unwarranted criticism, and repudiation by Dominican intelligentsia. Yet the disdainful behavior depicted in the many #MeToo stories about Diaz deviates from a Pulitzer Prize winner who is often described as refreshing, avant-garde for his sensitivity to issues of discrimination, humiliation, and whose work corroborated a shared reality of the immigrant experience.

But the man described by all the courageous women who dared to defy the academic establishment resembles that of Díaz’s emblematic persona of his prose, style, thematics, and “raw” language —Yunior— a young Dominican immigrant, whose objectification of women stereotypically embodies the machista traits of Latin American heterosexual constructed masculinity. Yunior does not think much of women. To him, women have “no real power,” and are merely disposable sexual toys to which he is entitled.

Yunior is Díaz’s Roy.

At this point, Díaz’s credibility is so damaged that many have questioned his decision to disclose having been raped as a child, calling it a strategic and preemptive move in advance of what he knew was coming. Perhaps. I don’t know. But one thing is clear: it is a very revealing essay.

If we read his confessional carefully, we can still perceive his narcissistic and self-important stance. Díaz seems concerned only with his well-being and suggests we take him at his word when he claims to have taken “responsibility” for his past. The author’s words don’t seem to carry much weight in the #MeToo era. And after Clemmons unmasked him and realizing he can no longer swagger his way through workshops and talks, Diaz left the festival early.

In Clemmons, Díaz found his past. As he recognizes, “No one can hide forever. Eventually what used to hold back the truth doesn’t work anymore. You run out of escapes, you run out of exits, you run out of gambits, you run out of luck. Eventually the past finds you.” And when it does, you run out of writers’ festivals.

Of course, the responsibility is not his alone. We cannot overlook the accountability of the white, liberal publishing establishment and their role in perpetuating the image of Latino heterosexual males as essentially woman-haters, and Latinas as promiscuous, powerless beings.

Junot Díaz did not rise to fame in spite of Yunior’s misogyny. Junot Díaz gained recognition because of Yunior’s sexist farce. It was through Yunior’s hanky-panky that the academic and printing elite published, promoted, and rewarded Díaz, making him a trademark of the Latino community, and in the process branding Yunior as the prototypical Dominican male. In this way, Díaz, recognizing his protected status, based his career and existence on misogyny, to the point that he could no longer differentiate the sexism portrayed in his fiction from his real life mistreatment of women—particularly women of color.

In the aftermath of the series of unpleasant truths about his conduct, Díaz issued a statement, which reads in part, “I take responsibility for my past. That is the reason I made the decision to tell the truth of my rape and its damaging aftermath.” His response to the accusations resembled that of actor Kevin Spacey. In his “apology,” Spacey essentially blamed his predatory behavior on his closeted (and not so secret) homosexuality. In a similar manner, Díaz wants us to excuse him because of what he endured as a child.

I do not want to undermine Díaz’s trauma, but we have to be cautious. What if Díaz’s abuser also suffered some sort of abuse, do we discount his trauma and pain? Do we exonerate his abuser? Absolutely not. We must empathize with Díaz and acknowledge his horrific experience as linked with his abusive behavior, but we cannot and must not allow it to simply explain and exonerate his actions. We can’t continue celebrating his pattern of humiliating and diminishing women.

My disappointment with Junot first emerged when I was a Scholar in Residence at Wellesley College. I came to see him read at Brandeis University. When I found out about the event, I was so excited because I was a fan. I was proud of his successes, not only as a Latina in graduate school, but as a Dominican woman who seemed to have much in common with this rising star. We shared similar backgrounds and were both Dominican immigrants who went to college.

I contacted him a few days before the event to introduce myself and tell him I was coming to see him. He was very receptive and friendly and told me he was looking forward to meeting me. After the talk, I walked up to him and he greeted me very warmly. “Marianella? Hi, how are you?” he said as he kissed me on my cheek like an old friend. He was so attentive that he asked his hosts if I could join them for dinner. They said yes.

After dinner, I got the chance to spend time with him and share more about my research. I was writing my dissertation on racial and national identity in Cuba and the Dominican Republic. At first, he was very engaging and warm. But as the night progressed, I noticed that his behavior became more and more hostile, especially after I told him to “slow down,” for he was moving too fast with his sexual advances. Perhaps he experienced my boundary as a rebuff, but it resulted in his turning deliberately mean. His comments and questions grew more and more unfriendly and sarcastic, which vexed me. This was a literary champion that I happened to like and admire. I told him I borrowed a friend’s car to come hear him read and meet him and that I didn’t understand why he was being such an hijo de puta?

When at one moment he commented on my hair saying, “Wow, a negrita with pelo bueno,” I looked at him, and said, “You didn’t! Don’t tell me you’re into that Dominican bullshit, racial hang-up of good and bad hair.” But he was so stunned about my “good” hair that he tried to pull my bangs back in a forceful way to see if it was true. I held my own, pushed back and told him he was being stupid, to which he said something to the effect of “You’re gonna tell me that ese pelito hasn’t gotten you places.”

Although I thought the subject and his comments surprisingly ignorant, especially coming from someone as brilliant as he, I realized something deeper was going on. His comments carried more complex meanings than they first appeared. He seemed to be trying very hard to find ways to make me uncomfortable and demean me by calling me “negrita.” He thought he was touching a nerve. And although he wasn’t harming me in the way he imagined (my own work focuses on the habitual denial of Africanity among Dominicans), I found his undeniable intent to hurt or degrade me alarming and even frightening.

At that point, I told him, “I think it’s time for me to leave. I have to drive back to Wellesley.”

And I left.

I didn’t have sex with Díaz that night. But who knows? Maybe I would have if Yunior hadn’t revealed himself to me so quickly.

I never saw Díaz or Yunior again. After Drown, I didn’t buy any more of his books.

No doubt it has been painful to find out that Díaz’s character is much more in accord with Yunior, the character, and that the split Junot/Yunior is difficult to separate, as Díaz himself recognizes. In a 2008 interview, Diaz declared his oversexed recurrent character to be his alter ego. But perhaps it’s the other way around, perhaps Junot Díaz only exists so that Yunior can have his way. Díaz is simply Yunior’s alibi.

And just as Roy needed to invent Aaron to enable his violence, Yunior hides behind the persona he has created in the sensitive Junot Díaz, the author and “golden brown boy” who enables his misogyny.

The man with the mask is not Junot Díaz. Junot Díaz is the mask. The man behind the mask has been Yunior all along.

There was never a Junot Díaz.

***

Marianella Belliard has Ph.D. in comparative literature. She’s a feminist and a theorist. She tweets from @MarianellaBell6.

[…] about. They can wash their hands of responsibility. But we all know Junot Díaz. We’ve read the accusations. Our collective silence speaks […]