It’s hard for any woman to go public with her story of being sexually harassed or abused by a man. She must deal with a dude who invariably denies everything. She’s gotta navigate a patriarchal society where police and the judicial system can be quick to discredit them. She has to manage the new trauma and retraumatization that come from having to defend herself and relive the abuse. No one does this just to get attention, just like no one would eat a box of thumbtacks to cure their hunger.

When the abuser is powerful or famous, as was Harvey Weinstein, the backlash is magnified. We now know Weinstein and others like him literally destroyed countless women’s careers and lives for daring to speak out. And while social media and the #MeToo movement have comforted survivors of this kind of royal douchebaggery with the realization they are not alone, standing up to men in power is still a very risky business, professionally, psychologically, and socially.

For Latinas and other women of color who call out prominent Latinos, these risks can be even greater because of added pressure to stay quiet for the “good of the community,” according to Loyda Martinez, a former Human Rights Commissioner and Women’s Commissioner for the state of New Mexico and a graduate of the Latina Leadership Institute. Latinas who speak out against famous Latinos are often rewarded with something along the lines of a good old Amish shunning, punished not only for not “knowing their place,” but also for airing the community’s dirty laundry for the rest of country to see.

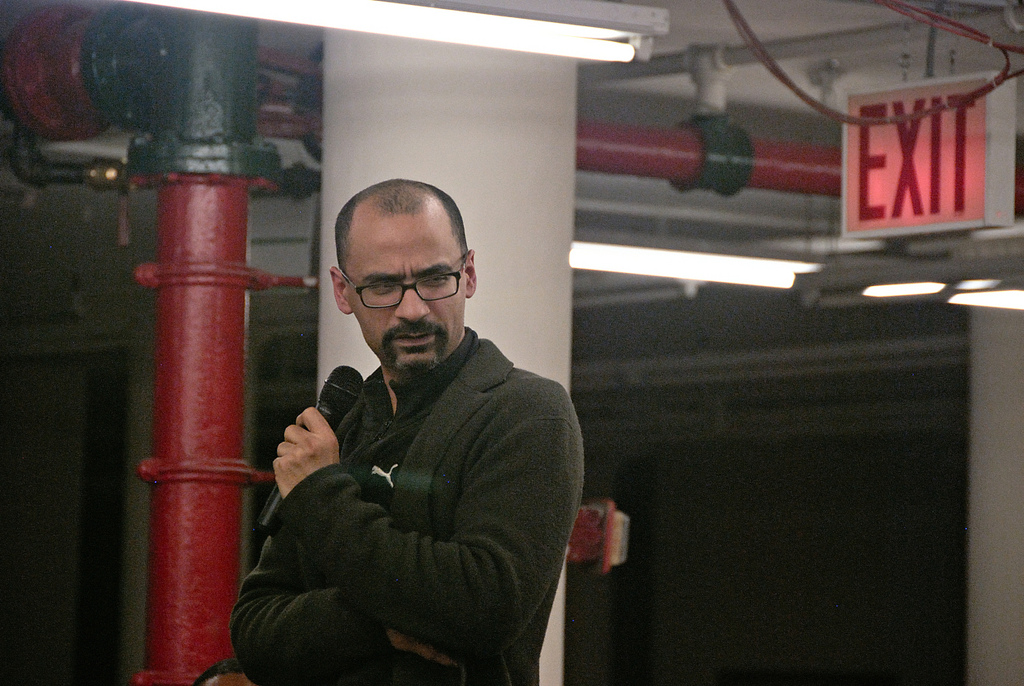

In the past week, we have seen descriptions of sexual misconduct by Pulitzer-winning writer Junot Díaz come from several women of color. Most notably, author Zinzi Clemmons got the world’s attention when she stood up in front of a crowd that had just listened to Diaz read his recent New Yorker piece about his own sexual abuse as a child, asking him if his abuse was why he had sexually assaulted her by cornering her and forcing a kiss upon her. Díaz then launched into a public tirade against Clemmons, and she fled the room, only to hear the crowd erupt into applause that she was gone.

Thanks to the #MeToo movement and Twitter, Clemmons’ story did not end there. Women who had been trying to get the world’s attention about Díaz for years stepped forward to defend and support Clemmons. The media paid attention. Díaz has stepped down from the Pulitzer Prize board, as both that organization and MIT (where Díaz works as a professor) conduct investigations.

I watched all of this with great interest, for I had tried to warn the world about Díaz more than 10 years ago in a blog post about his mistreatment of me when we dated 22 years ago. Ten years ago, I had been rewarded for this gesture by being discredited, mocked, taunted and threatened by leaders in both the Latino and publishing worlds, and by being punished by Díaz himself, through a clear and vindictive professional shunning and smear campaign. The whole thing was so terrible that I deleted my Twitter and blog in 2007, and did not revive them until this year.

While I’m glad to see Díaz finally being held somewhat accountable for his actions, I am still seeing far too many Latinos and Latinas —yes, mami, women can be pillars of patriarchy too— asking me and other Latinas to, you know, stop ruining m’ijo’s pretty career, to get out of the way, that boys will be boys, that if m’ijo didn’t rape us or beat us then we should stop making a big deal out of nothing, on and on and on. Of those who have publicly denounced Díaz, most have been non-Hispanic whites or non-Hispanic blacks. Latino community leaders, so far, still remain pretty much callados y cobardes.

The Díaz situation, while highly visible, is far from unique. In the past three months alone, several other prominent Latinos have gotten into trouble in the era of #MeToo. Predictably, few in the Latino community seem to care.

A Harvard University professor named Jorge Domínguez was asked to take an early retirement after his decades of sexual assault and harassment were detailed in a story in the Chronicle of Higher Education. The university had known about the abuses for decades and had not only done nothing about it, they’d given him tenure and forced one of his victims, another professor, to resign. This speaks to a third element going against those who accuse prominent Latinos of misconduct, which is the seeming reluctance on the part of non-Hispanic white institutional leadership to punish men of color, lest they be seen as behaving like racists. Oh, and for the record, giving Domínguez a fat pension and setting him free upon the beaches and golf courses of the world seems an unsatisfactory way to deal with a vindictive predator who repeatedly used his power the intimidate and humiliate female students and colleagues.

Earlier this year, the President and CEO of the United States Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, Javier Palomarez was forced to step down by the board, after they finally decided to reckon with his many indiscretions. It appears that his “financial improprieties” played a bigger role in his ouster than did, you know, him trying to sexually force himself upon his former chief of staff, Gisselle Gazek Nicholas, in 2012, or the fact that he fired her when she refused his advances. Because, presumably, boys will be boys.

Javier Palomarez (Via his Facebook page)

In March, celebrity stylist and Los Angeles fashion icon Barrio Dandy was outed in a blog post by a woman named Lucy L., for abusing her in a variety of ways, including refusing to be there for the birth of their child or, when the baby died, refusing to help plan or attend the funeral. Lucy says she was rewarded for this heartbreaking honesty by being mocked and harassed by the pinup community in which she had modeled and over which he apparently still reigns. “He destroyed my life,” she told me, “and everyone believes his gaslighting. Everyone turned against me for telling the truth, but the worst of them were the other women who took his side.”

And just this month, sexual assault allegations against California Democrat Rep. Tony Cárdenas have surfaced. According to reports, Cárdenas is being accused of sexually assaulting a 16-year-old in 2007. The accuser, now 27, filed a civil suit in April against Cárdenas, who holds a leadership position in the current crop of House Democrats. So far, Democrats have been cautious to speak out against Cardenas. CNN reports that Cárdenas “has vehemently denied the claims.”

Rep. Tony Cárdenas (Public Domain)

In an Associated Press story last year, #MeToo movement founder Tarana Burke said Latinas and other women of color are much less likely to report powerful men of color, because their dual marginalization makes the stakes unbearably high. Among all marginalized women in this country, Latinas are the most marginalized, making just 54 cents to every dollar earned by a white man; black women earn 64 cents; white women, 79.

“Latina women feel more vulnerable to retaliation if they report incidents because most of us are in working-class jobs,” says Martinez. “Any promising career literally ends for us.”

Latinas are also by far the most underrepresented women in U.S. film and television —arguably the nursery in which mainstream cultural norms and expectation for “type” are hatched— getting less than two percent of all film and TV roles, according to a USC diversity report. What few roles we do get are predictably disempowering—maids, prostitutes, criminals. Latinas who grow up on this fare, in a mainstream society that doesn’t even see them, in a Latino subculture that treats them as second-class citizens, will probably disproportionately lack the confidence to confront her abusers. Suicide statistics bear this out, with young Latinas being the most likely of all Americans to kill themselves.

Screenwriter Ligiah Villalobos last year created a litmus test in which, to pass, a film needed to have at least one Latina character with a speaking role, who was an educated professional. In all of 2017, only one film passed. It was Zootopia, and even then, the character was still sexualized. While this might seem unrelated to the Díaz, Dominguez, Palomarez, Dandy and Cárdenas stories, it isn’t. Governments pour billions into propaganda in the form of entertainment media, because film and TV are where people learn how to think about each other, and themselves. And how we think about each other and ourselves determines how we treat each other, and ourselves. Things aren’t much better for Latino males in this regard; they make up a little more than 3 percent of all roles, and most of those are for rapists, murderers, drug dealers and the like.

So, you know. We need heroes. We all need heroes. The popular culture doesn’t give them to us. So when one of us manages, in spite of all this, to rise to the top of his field, I get it that we all want to cheer. We all want to see ourselves in that person, because we aren’t seeing ourselves as people like that person anywhere else in our culture. I get it.

But I also get it that silencing Latinas in order to protect powerful Latinos who abuse them is not good for any of us, except the predators. We all need heroes, yes; but not at our own expense, and not these guys. Every time we make excuses for them, or look the other way, or shame the women who confront them, we are telling ourselves and our community a lie, that goes like this: We can’t do better.

Yes, we can.

We have heroes waiting in the wings, and booting out the sinvergüenzas among us won’t diminish the ranks of Latino heroes. We have heroes. They are us, the women and men speaking out against oppression, it all its forms—and this must now and forever include sexual misconduct, abuse, and harassment.

Stop telling Latinas to sit down and shut up. Stop ignoring Latinas who speak up, and start promoting and uplifting their voices. Support them, instead of their tormentors.

***

Alisa Valdes is a screenwriter, bestselling novelist and former staff writer for the Boston Globe and Los Angeles Times. She tweets from @RealAlisaValdes.