By Emily Corona

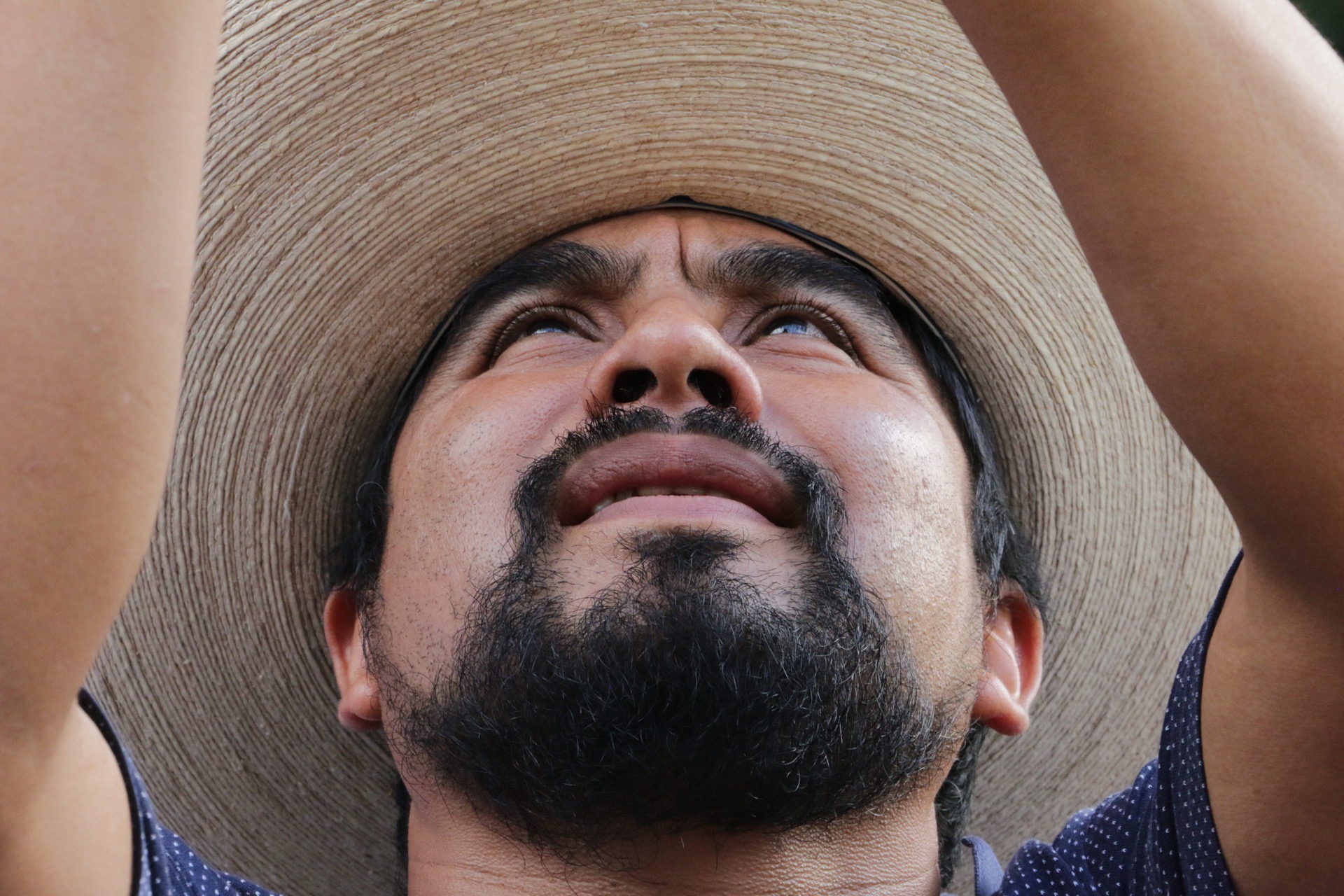

María de Jesús Patricio or Marichuy. (Photo by Emily Corona)

A few days before Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s landslide victory as president-elect of Mexico and as he addressed the people of Guerrero and Michoacán, an early opponent, one backed by the country’s most radical anti-capitalist leftists representing its largest coalition of organized Indigenous communities, toured the northern states of Nuevo León, Coahuila and Durango. Wherever she went, with quiet determination, María de Jesús Patricio would pull out her pretty embroidered notebook with the initials “EZLN” stitched onto the back in pink, and took notes as she listened to the stories of mothers of disappeared children.

For starters, Marichuy, as she is affectionately known, never really aimed to become president of Mexico, as she stated repeatedly from the start of the campaign. Her plan was to focus attention on the troubling realities of land dispossession, environmental pollution, human rights violations and the everyday deprivations of her Indigenous followers, who represent some 10 percent of Mexico’s total population. She traveled throughout the country to give what her supporters described as an “articulation of the resistances.” In Marichuy’s words, “If they are going to kill us one by one they might as well try and kill us together; let’s make it harder for them.”

Her campaign began nearly two years ago, in October of 2016, when the Indigenous Zapatistas from Chiapas and the National Indigenous Congress of Mexico made the momentous decision to reverse their two-decade-old refusal to engage in electoral politics. They formed a national Indigenous Governing Council and, seven months later, elected Marichuy, an Indigenous Nahua and traditional healer. She became their spokeswoman and candidate in the 2018 presidential elections. She comes from Tuxpan, a community in the central area of the Pacific coastal state of Jalisco.

On October 7, 2017, national electoral authorities recognized Marichuy’s plan to run for president as an independent, meaning she did not have the backing of a political party. That gave her 120 days to collect roughly 900,000 signatures from at least 17 of Mexico’s 32 states, which would represent one percent of the country’s registered voters list.

There were perils along the way. On January 21, unidentified gunmen stopped and attacked a press van that was following her caravan in Michoacán. A month later, only days before the signatures were due, a highway accident on the arrow-straight roads of Baja California left one of the 11 people on board the campaign van dead and Marichuy with a fractured arm.

An even greater impediment was technological. As the days ticked by, it became clear that Marichuy was in danger of missing the deadline, her efforts severely hampered by the system established for registering signatures: a telephone app compatible only with specific mobile devices too pricey for most Indigenous Mexicans to own. Nonetheless, she spent four months crisscrossing the country to hear the concerns of members of 60 of Mexico’s Indigenous tribes.

“We discovered that the National Electoral Institute was designed with the rich in mind,” Marichuy would say months later during a press conference in Monterrey. Not only did the lack of the right phone present a block, but the electoral institute’s system required adequate Internet coverage. That meant volunteers collecting signatures in remote localities had to travel sometimes many hours to find a decent enough connection to relay the signatures.

Wherever she went, María de Jesús Patricio would pull out her pretty embroidered notebook with the initials “EZLN” stitched onto the back in pink. (Photo by Emily Corona)

In the end, the barriers proved too great, even after the authorities began allowing the submission of signatures on paper. When the February 19 deadline rolled by, Marichuy’s movement was some 600,000 signatures short of the 900,000 needed to put her on the ballot.

Even in failure, Marichuy’s campaign stood out for its honesty. Election officials invalidated only five percent of Marichuy’s signatures for inconsistencies against 58 percent of those of fellow “independent” candidates Jaime Rodríguez, known as “El Bronco,” the governor of Nuevo León. His were faulted for both inconsistency or outright forgery. The invalidation rate for former first lady Margarita Zavala was 45 percent and for another “independent,” Senator Armando Ríos Piter, officials invalidated a scandalous 8 out of 10 signatures as forged.

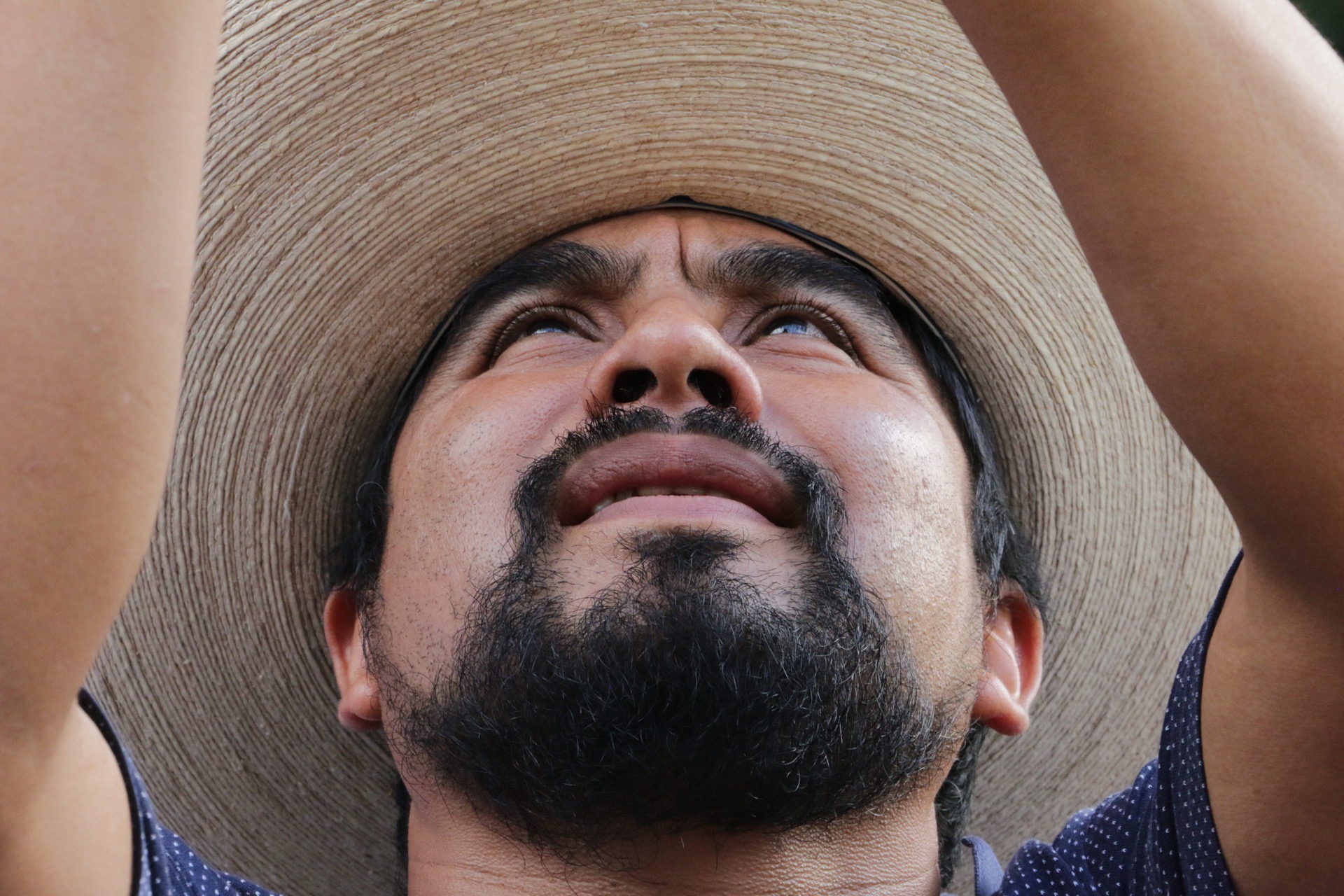

Did the Indigenous Governing Council consider its failure a missed historical opportunity? I asked Oscar Espino, a Totonaca Indian from Veracruz and a member of the council. His answer sidestepped the question. “It was a very good opportunity to position our agenda,” he said, “but we feel it was more of a loss to the entire country than a loss for us. We all missed the possibility of listening to one another.”

Oscar Espino, Totonaca Indian from Veracruz and a member of the council. (Photo by Emily Corona)

After the road accident, Marichuy suspended her tour. With no true independents to oppose López Obrador, the campaign rolled on. Support for the anti-graft platform of AMLO’s Movement for National Regeneration (whose acronym, Morena, alludes to the mestizo-construct of the Mexican nation) grew in force, spurred by profound disenchantment with the mainstream political parties.

A week-and-a-half before election day, Marichuy ended her three-month hiatus with a two-day appearance, again in the Baja California peninsula. A few days later, she appeared in industrial-driven Monterrey in Nuevo León, and in the violence-stricken cities of Torreón and Saltillo, in Coahuila.

Marichuy ended her three-month hiatus with a two-day appearance in the Baja California peninsula. (Photo by Emily Corona)

In a country where women tend to become progressively masculinized as they rise in the power echelons of politics, the stillness of Marichuy’s style stands out. Other writers have noted her deference to other women in public appearances, mindful of her triple exclusion as a woman, and a woman of Indian heritage in a largely patriarchal society.

I met her for the first time on a muggy morning in the northern city of Monterrey. The trip was kicking off with a press conference that took place at a prominent social anthropology research center. Accompanied by two fellow members of the Indigenous Governing Council, Marichuy explained her candidacy and role. She told local reporters how the coalition of organized Indigenous communities stemmed from the Zapatista Army of National Liberation armed uprising of 1994. She spoke of how two years later, betting on the San Andrés peace dialogues that took place in Chiapas, the Zapatistas or EZLN called for a space of encounter between all the Indigenous peoples of Mexico, and how they had all walked together since then.

Marichuy and Bettina Cruz, from the Indigenous Governing Council, during an encounter with women in Monterrey. (Photo: by Emily Corona)

The council’s diagnosis of the current Mexican situation is that the problems and repression that Indigenous communities experience also affect the cities and non-Indigenous parts of the country, although its manifestations may vary. The state’s infrastructure, the council charges, is based on plunder and dispossession. Before election day July 1, Oscar Espino, the council member, warned that regardless of who would win, the energy reforms made by the exiting administration would go into effect in any event, and “we will lose.”

The trip was Marichuy’s first to Nuevo León and Coahuila, making them the 26th and 27th states in her travels as a spokesperson for the council. The scenes were very different from mid-October of last year, when she kicked off the campaign trail in the highlands of Chiapas, bulwark of the EZLN. Then, thousands of Tzotzil, Tzeltal, Tojolabal, Ch’ol and Mam Zapatistas streamed into the autonomous communities, where the Zapatistas self-govern their communities’ education, health and local justice. In that period they welcomed her with flowers, confetti, band music and pride in knowing that their spokesperson might make history as the first Indigenous woman to run for president in Mexico.

This time, the welcoming crowd was just as affectionate but more sparse, and those who received her were mostly non-Indigenous. They were teachers protesting current President Peña Nieto’s contentious education reform; university students disappointed by their prospects after graduation; communist youth, social anthropologists, and feminist groups; an entire town under the threat of relocation, relatives of the victims of the mining disaster of Pasta de Conchos, immigrant activists, members of the church and relatives of victims of femicide and forced disappearances.

In their company, the democratic, civic, institutionally strong and optimistic portrayal of Mexico put forth by some of the other presidential candidates seemed very far away. This desert was not the land of the unforgettable “Saving Mexico” of the 2014 Time magazine cover. Rather, it was as the priest Pedro Pantoja —who has sheltered more than 500,000 immigrants— described it: a land of immigrants, hungry peasants and exploited workers and a “paradise for organized crime and corrupt politicians.”

Blanca Martínez, from the Coalition for Our Disappeared in Coahuila, said that starting in 2006, the northeast part of the country became a disputed territory between drug cartels and the laboratory for a new strategy to exterminate the local population. Just a few days before, she said, she had been in the locality of Miguel Alemán in Tamaulipas state, where the district attorney had agreed to exhume more than 300 bodies from a mass grave. Relatives were lining up to deliver blood samples for DNA testing that they hoped would not produce a match. “What keeps these families going is the hope that they will find their loved ones alive,” Martínez said in Saltillo on the last day of the tour. With more than 100,000 people killed in the past decade, close to 30,000 non-identified bodies and hundreds of thousands of body fragments strewn across the desks of public ministries and morgues, she said, “it would seem this tragedy only leads up to more death and the cemetery.”

On June 27, as López Obrador packed the Azteca stadium in Mexico City for his closing campaign rally, and the Mexican soccer team hoped to beat Sweden and make the quarterfinals of the World Cup, a few dozen people gathered in a roofed sports court at the local public university in Torreón, Coahuila. They were students, human rights defenders and people looking for their disappeared relatives. In suffocating 93-degree heat, a few organizers prepped the table as they waited for the van with Marichuy and her council companions to arrive. There was no talk of the elections here. Faces of young men and women stared back at us from banners that waved slightly under the breeze with messages, such as, “Have you seen him? Hugo Marcelino González Salazar. Disappeared on July 20, 2009 in Torreón, Coahuila,” or “I was disappeared on May 1, 2010. Jesús Daniel Flores García.”

Marichuy eventually arrived, flanked by Espino and Bettina Cruz, an Indigenous Binnizá human rights activist from the Tehuantepec Isthmus in Oaxaca. In the parking lot, a small group of reporters pressed Marichuy to comment on the upcoming election. “Vote or don’t vote, but organize amongst yourselves,” she said. They then weaved their way through the parking lot, the dry seeds of pointleaf manzanita trees crackling under their feet. They seated themselves at the table under the banners in honor of the disappeared youth.

Lucy López Castruita was among them. Her daughter disappeared 10 years ago, shortly after she turned 17. Castruita had searched for her ever since in prisons, psychiatric hospitals and other forlorn places where nobody else was looking. “When you see a person living in the street, take a photo of them and post it on Facebook,” she urged. “We found a kid in Veracruz that was from Guerrero that way.”

Kristian Karim Flores, the son of Lourdes Huerta, disappeared August 12, 2010. He left en route to Coahuila for work, with his brother-in-law in a van carrying chocolates before the earth seemed to have swallowed them whole. The quest for justice of the families has resulted in a swamp of paperwork and not much else.

Kristian Karim Flores, the son of Lourdes Huerta, disappeared August 12, 2010. (Photo by Emily Corona)

The pain and sorrow of these families are among the reasons the Marichuy campaign matters beyond the electoral cycle and the failed attempt to make the presidential ballot. It matters because, as Marichuy said, her supporters want life and they want it for everyone. “What we care about is you and that is why we are still traveling the country, because we want to know if you agree that our fight is your fight as well,” she said when she addressed the mothers of the disappeared, the immigrants and others among the dispossessed.

A few dozen yards away, cars whizzed by, oblivious to the meeting that was taking place under the roof of the university court. “If fighting for life means being against the laws,” Marichuy told those assembled, “then so be it. We shall fight that way.”

***

The reporting done for this article was possible thanks to a Tinker Foundation Field Research Grant that the author was awarded through the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at NYU.