Erik (HASH) Hersman/Flickr

I’d just moved to Colorado from Arizona for graduate studies and it was voting time. Although young, I felt extremely prepared and proud to be performing my civic duty again. Looking down and ready to search her list of registered voters, the older election volunteer asked my name. When I told her, her head snapped up and refusing to take my pro-offered ID or look at her registration list, she told me to go to the precinct where I “belonged.” I wasn’t leaving so I figuratively dug in my heels. After repeating my name and telling her three or four times to check her list, the election’s volunteer —begrudgingly— found my name.

I didn’t have a name for it at the time, but it’s called voter intimidation and it’s an age-old method of voter suppression often used to silence peoples’ votes (and by proxy their voices), particularly voices of people of color, across our nation. It’s defined in federal law (18 U.S. Code § 594) as anyone intimidating, threatening, coercing or attempting to do the same of any person voting or attempting to vote and is punishable by imprisonment or fine or both.

Sadly, my experience is not uncommon and indeed mild in comparison to other voter intimidation incidences in past recent elections. Trained volunteer elections observers at precincts in the majority-Hispanic Point Neighborhood in Salem, Massachusetts, reported violations of Latino voters encountering hostility, improperly being asked to present identification and denied legally allowed translation services in the 2012 and 2014 elections. The NALEO Education Fund reports in their survey that during the 2016 election a notable number of Latinos experienced intimidating or discriminatory behavior committed against them by election officials—and the rate for Latinos being harassed or bothered while trying to vote is more than twice that of white Americans, according to a joint survey by the Public Religion Research Institute and The Atlantic.

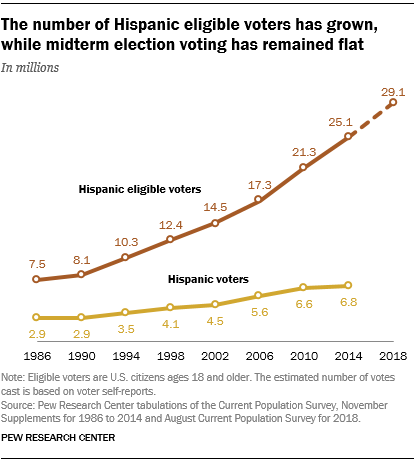

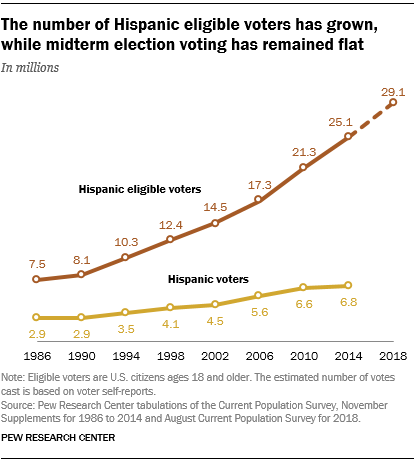

In our current political climate, these statistics are alarming because the stakes of this mid-term election results are so high. So you can imagine the eye-opening revelation I had when a couple of weeks ago, I randomly came across a 2015 statistic by the Pew Research Center that every 30 seconds a Latino turns 18 and thereby becoming eligible to vote. That’s 800,000 eligible new voices every year. The same center also reports that next week, more than 29 million Latinos, 12.8% of all voters in our country, are eligible. Let me repeat that: 29 million Latinos in our country are eligible to vote next week. That’s a powerful lot of voices. Additionally, 71% of eligible Latino voters are concentrated in six states (California, Texas, Florida, New York, Arizona and Illinois) in which three (Texas, Florida and Arizona) are home to key, very tight U.S. Senate races. Yet, despite the numbers, the number of Latinos voting in midterm elections hasn’t really grown since 2006. Will this be the year that changes that?

That kind of voting experience in Colorado was a first for me. If that were to happen to me today, I’d still insist on my right, but I wouldn’t keep it to myself. I’d report it immediately to an elections protection hotline (866-OUR-VOTE or 888-VE-Y-VOTA).

Now, more than ever, we cannot let our voices be silenced.

***

Rhonda Gonzalez is health and nutrition programs manager for Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona and a Public Voices Fellow of the OpEd Project.