Protesters depicting detainees of the U.S. detention facility at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. (AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis)

By A. Naomi Paik, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, is force-feeding nine detainees who are on a hunger strike at a detention center in El Paso, Texas.

The protesters are mostly from India and are being held in ICE custody while their asylum or immigration cases are processed. Since the beginning of the year, they have been protesting their detainment and mistreatment by guards who they allege have threatened them with deportation and withheld information about their cases, according to the detainees’ lawyers.

In mid-January, a federal court ordered ICE to force-feed the strikers. An ICE official stated: “For their health and safety, ICE closely monitors the food and water intake of those detainees identified as being on a hunger strike.” ICE policy states that the agency authorizes “involuntary medical treatment” if a detainee’s health is threatened by hunger striking.

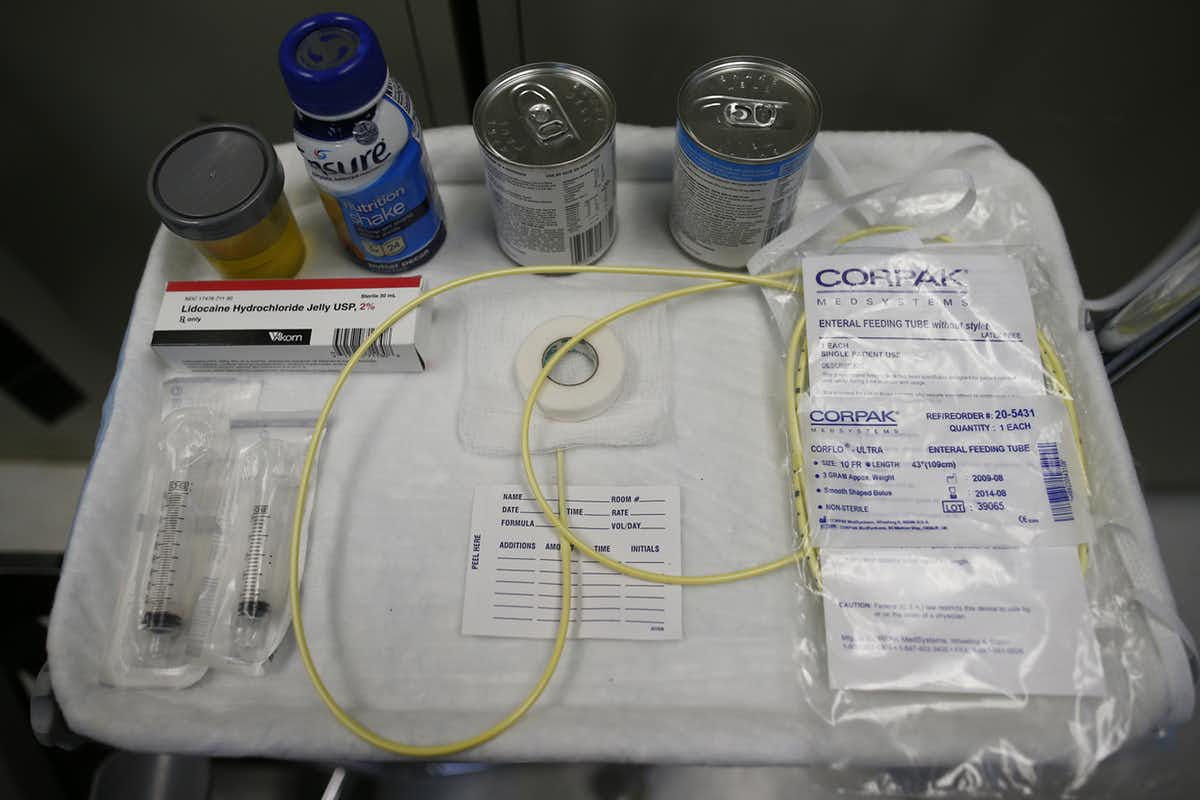

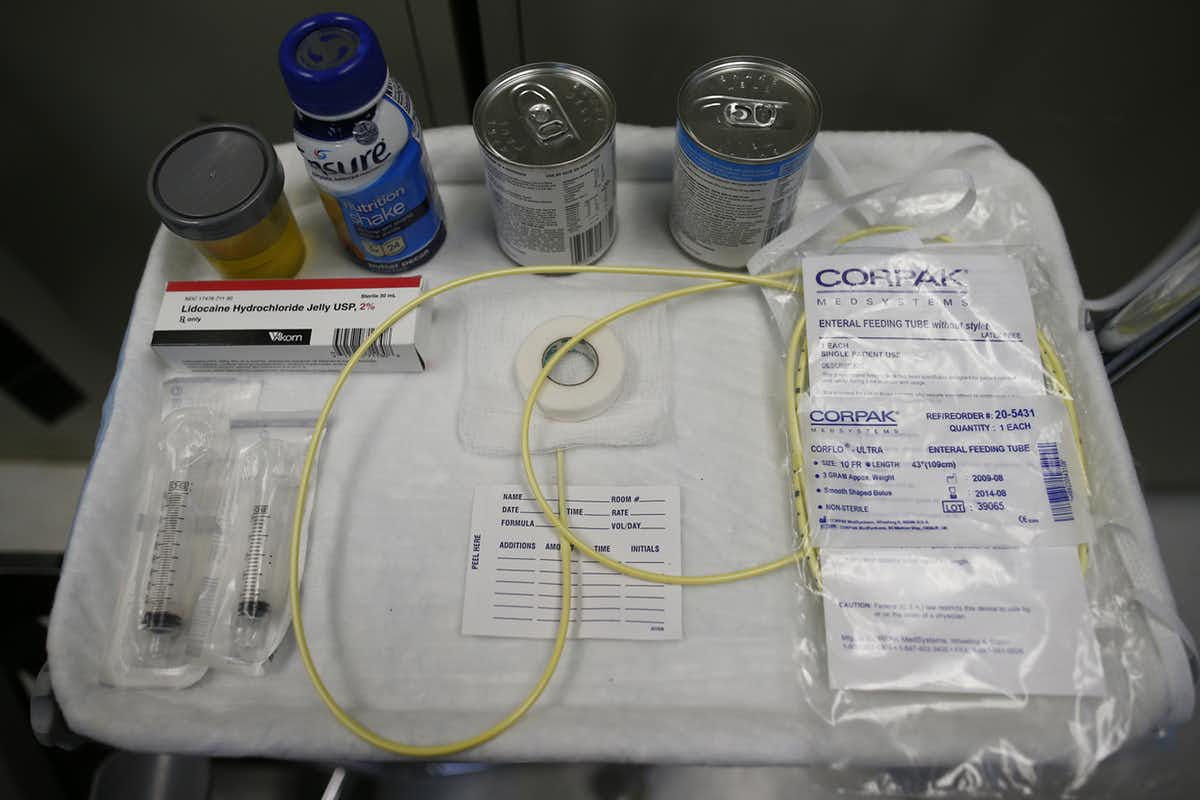

Force-feeding involves tying a detainee to a bed, inserting a feeding tube down the nose and esophagus and pumping liquid nutrition into the stomach. ICE detainees have reported rectal bleeding and vomiting as a consequence of being force-fed.

As I write in my book Rightlessness and research published elsewhere, this is not the first time U.S. government agencies have force-fed people in its custody.

Since 2005, the U.S. military has force-fed detainees at the Guantánamo Bay naval base whenever they would go on a hunger strike to protest their indefinite detention.

Force-Feeding at Guantánamo

The U.S. military has indefinitely detained individuals at Guantánamo who it alleges are enemy combatants in the “war on terror” since 2002.

Hunger strikes have plagued Guantánamo since it opened in 2002. In one of the largest hunger strikes to occur in a U.S. detention facility, about 500 detainees stopped eating under the slogan “starvation until death” in late June 2005.

They began this strike to protest the conditions of their confinement, including alleged beatings, abuse of their religious freedom by mishandling the Koran and indefinite detention without trial.

Nutritional shakes, a tube for feeding through the nose, and lubricants, including a jar of olive oil, are displayed as force feeding is explained during a tour of the detainee hospital at Guantánamo Bay Naval Base, Cuba. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak)

In response, military doctors authorized “involuntary intravenous hydration and/or enteral tube feeding”—in other words, IV treatment and force-feeding.

Prisoners found ways to get around the feedings, like making themselves vomit or siphoning out their stomachs by sucking on the external end of the feeding tube.

The strike overwhelmed camp commanders. In December 2005, they called in help from the Federal Bureau of Prisons, which had previously authorized force-feeding. The consultants observed as strikers were force-fed twice a day and recommended using the emergency restraint chair, a “padded cell on wheels.”

That requires strapping detainees down onto the chair, making it easier for guards to insert and remove a feeding tube. Detainees referred to it as the “execution chair.” This had the desired effect on the prisoners: Only a handful continued the hunger strike and it was over by February 2006. The camp ordered 20 more chairs.

A Painful Process

In 2013, a widespread hunger strike again swept through Guantánamo—106 of 166 prisoners participated. Forty-one detainees met the requirements for being force-fed: skipping nine consecutive meals or their BMI dropping below 85 percent of their intake weight.

One participant, Samir Naji al Hasan Moqbel, a Yemini citizen detained for 11 years, told The New York Times, “I had never experienced such pain” as from the feedings.

A U.S. Navy nurse stands next to a chair with restraints, used for force-feeding at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Cuba. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak)

Detainees who participated in the numerous strikes over the years have consistently described the force-feeding process, including having teams of five guards who hold down the prisoner, as torture. Some reported being overfed to the point where they vomited up what was forced down their throats.

“I will not eat until they restore my dignity,” Moqbel said. He said he hoped “that because of the pain we are suffering the eyes of the world will once again look to Guantanamo before it is too late.”

Legal Challenges

Guantánamo hunger strikers filed lawsuits against the U.S. government for force-feeding prisoners and using the restraint chair.

Several judges ruled that force-feedings are legal. In one case, a judge wrote that it did not constitute a violation of the Eighth Amendment against cruel and unusual punishment. Rather, she wrote that administrators “are acting out of a need to preserve the life of the Petitioners rather than letting them die.”

This contradicts what many experts the medical and human rights professionals have said about force-feeding.

The World Medical Association, an international medical ethics organization, asserted that force-feeding is “unjustifiable.” Organizations ranging from the ACLU to Human Rights Watch condemn the practice as “inherently cruel, inhuman, and degrading.”

Another federal judge in a 2009 followed a Supreme Court ruling deciding that courts have no jurisdiction over Guantánamo—a camp physically located in Cuba but governed by the United States.

Similarly, federal courts have limited power to intervene on behalf of the ICE detainees because immigrant detention is not considered punishment and thus not protected by due process rights. In Wong Wing v. United States(1896), the Supreme Court ruled that “the Constitution does not apply to the conditions of immigrant detention.”

While the courts can authorize interventions requested by the government such as force-feeding, immigrant detainees have limited power to appeal to courts about the conditions of their detention.

As with the Guantánamo detainees, migrants are risking starvation, but not because they want to die. As Amrit Singh, the uncle of two men being force-fed, stated, “They want to know why they are still in the jail and want to get their rights and wake up the government immigration system.” Hunger striking offers one of few ways they can protest their prolonged confinement in pursuit of this goal.![]()

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.