Editor’s Note: The following piece was originally published at Migrant Roots Media. The author contacted us and gave us permission to republish her work here.

In recent years, Central American migration to the United States has steadily caught the attention of media and policy outlets as the number of children and families fleeing violence and poverty has more than doubled. It is estimated that Guatemalan, Salvadoran, and Honduran youth represent a large percentage of unaccompanied minors who arrive in the United States. Many of these children, who are under the age of 17 and travel without an adult, migrate to the United States to seek family reunification and to escape widespread violence, targeted persecution, and economic uncertainty. Recently, a large immigrant caravan, mostly of children and adults from Honduras, also made their journey to the U.S-Mexico border to seek asylum. This mass exodus is a response to the pervasive social and economic conditions in the Northern Triangle and the political unrest that followed the highly contested elections in Honduras almost two years ago.

Although I am glad to see attention finally given to the current plight of Central American refugees and migrants, I am appalled by the ways we continue to overlook decades of U.S. policy intervention in Central America and fail to connect how it has fueled migration since the 1980s. In doing so, we continue to ignore the long history of violence against Central American peoples and their historical and socio-political experiences and analyses.

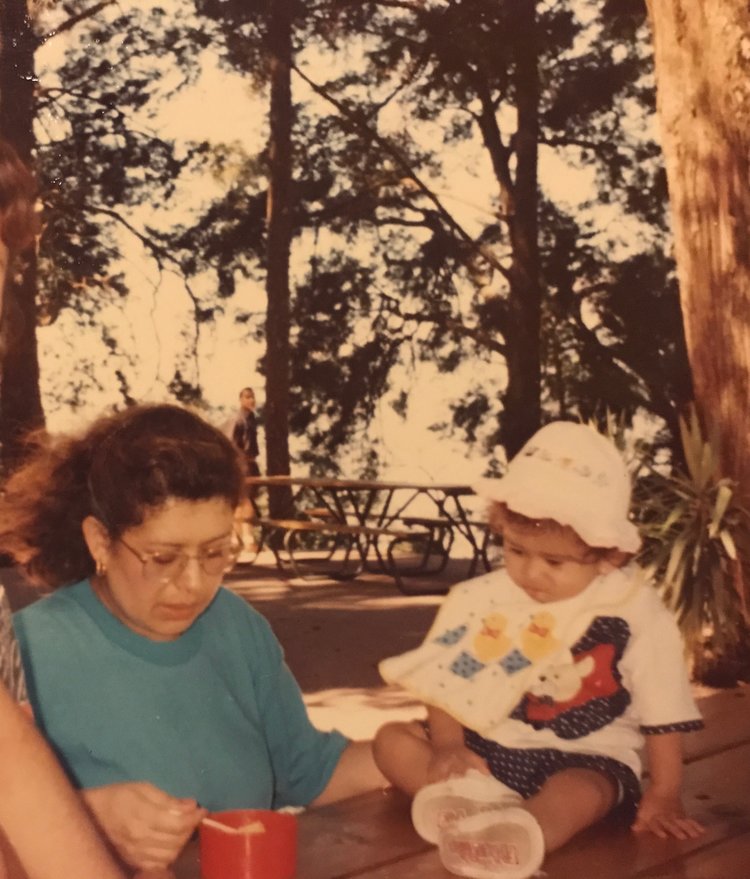

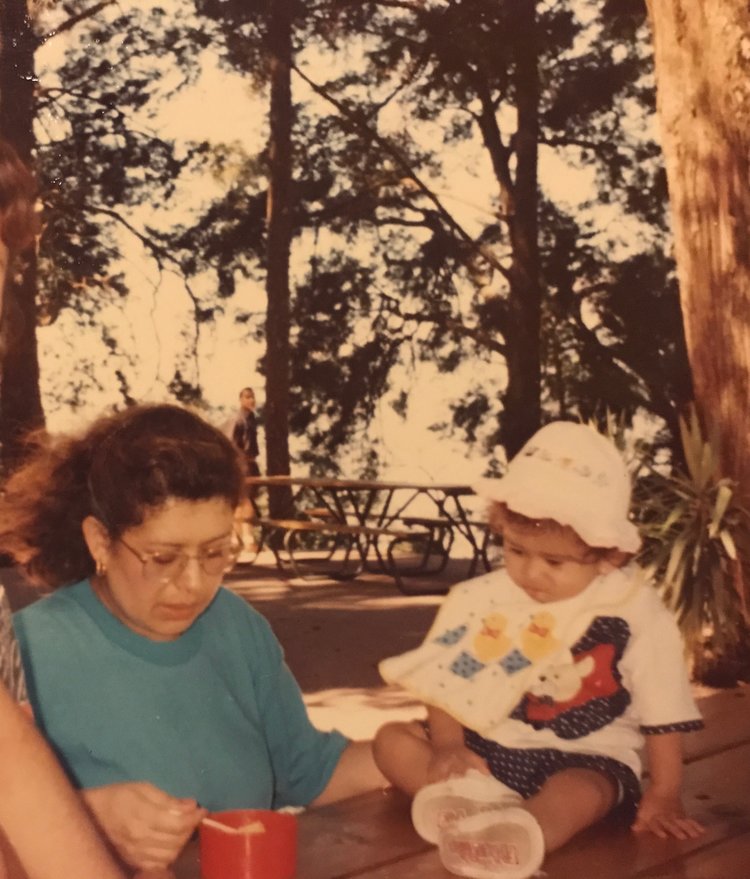

Central American migration to the United States is not a new phenomenon. In fact, the migration patterns of Central Americans can be traced back to the early 1980s when the Northern Triangle faced severe economic, social, and political instability. For example, the Salvadoran Civil War, which lasted approximately between 1980-1992, has been identified as the surge of Salvadoran migration to the United States. Even though political conflicts might have “ended”, the daily strife and battle with death did not, and Central American families lived among the remnants of U.S.-fueled wars and genocide. The uncertainty and fear caused by social and economic instability led many families like mine to migrate to the United States. The first to leave El Salvador was my father, who left in search for social and economic mobility, and a few years later, my mother and I, who yearned for family reunification.

My mother and I at El Teleférico de San Jacinto in San Salvador, El Salvador (1996).

As a five-year-old, migrating to Los Angeles marked the onset of my identity as a child of the Central American diaspora—a demographic that is now the third largest group of Latin Americans in the United States. According to the Migration Policy Institute, Central Americans represent approximately 3.4 million residents and over 8 percent of the total immigrant population with enclaves across major metropolitan cities such as Los Angeles, Washington D.C., and Houston. There is no doubt that the demographic growth and trends of Central Americans raise important questions about our incorporation to the United States, our social and political attitudes, and also how we view ourselves in the ethnoracial stratification system.

In her seminal book Race Migrations, sociologist Wendy Roth contends that when leaving a country behind, it is not only the physical person who migrates, but also their ideas of race, nationality, and culture. Her work reminds us that we cannot entirely study race without considering migration. This reinforces the fact that race and ethnicity are dynamic and depend on multiple factors, not static and straightforward. For instance, there are multiple contextual factors that can shape someone’s understanding of their ethnoracial identity, such as phenotype, socioeconomic status, regional location, and socialization by the family. As an immigrant, I have always found the family structure to be particularly important because, as Roth points, “parents and close relatives provide children with their first, and often most influential, understanding of their emerging sense of self.” In my own experience, my immigrant parents have played a key role in transmitting critical pieces of information which have helped me crystalize and make sense of my ethnic identity.

In my own research, I similarly consider the family unit to examine racial identity formation among Central American young adults. Thus far, I have observed that Central American youth view their parents and close relatives as cultural transmitters who pass down intimate stories full of cultural knowledge about migration and their homelands. This allows Central Americans who come to the United States at a young age, or who were born here, to construct knowledge of their home countries through second-hand methods that are mediated by the stories and memories others share. Ana Patricia Rodríguez further explains that Central American familial oral histories allow 1.5 and second-generation immigrant youth to revisit sites of war, displacement, migration, and cultural trauma lived first-handedly by their parents.

Growing up, my most heartfelt memories were spent in my uncle’s hammock while my family shared cuentos or stories about their life in El Salvador. For Central American families, reminiscing about the past may trigger painful memories of war and genocide, and recollections that many would rather forget and protect others from knowing. Because these stories were not often shared, I quickly learned to appreciate them as they exposed me to important parts of my history. Without being fully conscious of it then, my family became the first to give me a historical analysis of U.S. policy intervention in Central America and provide nuanced ways of thinking about migration.

A story that always stood out was my uncle’s story of migrating to the United States and the role social networks played for those leaving home and coming to this nation. My uncle vividly recalled the fear he felt while crossing three international borders (Guatemala, Mexico, and the United States), and the consuming nostalgia he felt for leaving his mother and rest of his family behind. Traveling with a group of friends who had pre-established social ties with other Salvadoran immigrants in Los Angeles, however, was one of the few things that kept him at ease. My uncle was fortunate to be welcome to Los Angeles by a network of immigrants who helped him settle in to life in this country, connected him to blue-collar jobs, and provided emotional support. In my uncle’s case, immigrant social networks played a significant role in his life as they provided him with critical assistance during his first few months in the United States. Getting a job quickly allowed him to regularly send remittances back to El Salvador.

The cuentos my family shared also unearthed distant memories of my life in El Salvador, like the Mayan ruins located near my childhood home where my abuelita often took me, and reminded me why I should always be proud of where I was born. It was common to feel what Neda Maghbouleh describes as inherited nostalgia, in which immigrant youth try to make sense of their ethnic identity by coming to peace with their familial histories, both in the diasporic present and in the paternal country.

As the U.S. Central American population continues to grow, it is our duty to acknowledge their historical and socio-political experiences, through platforms like Migrant Roots Media, and continue to make connections between the past and the present to create spaces, physical and in our narratives, where we can build a world where the dignity of all human beings is respected and affirmed.

***

Adriana Cerón recently graduated from Pitzer College with a BA in sociology and a minor in Chicano/a-Latino/a Studies. She is a Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow interested in the integration, attainment, and mobility of Latinos in the U.S., with a particular focus on U.S. Central Americans. Adriana was born in El Salvador and at the age of five migrated to Los Angeles, CA, where she has lived since. Twitter: @_Adriana_Ceron.