LAS VEGAS — Today, February 17, is the 91st birthday of the League of United Latin American Citizens.

Launched mostly by Latino veterans of the First World War, LULAC has become the nation’s preeminent Latino civil rights organization, essentially what the NAACP is for black Americans, championing the economic and social rights of Latinos. With over 100,000 members in the United States and Puerto Rico, LULAC strives for the full inclusion of Latinos in American society, by emphasizing assimilation, educational achievement, job training, and civic engagement.

LULAC attorneys won an early victory against school segregation in 1945, Mendez v. Westminster, in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit found that the “schools for Mexicans” in Orange County, California, were unconstitutional on the same basis that the Supreme Court would claim eight years later in Brown v. Board of Education: that, despite what the Redemption Court had claimed in Plessy v. Ferguson back in 1896, segregated schools are “inherently unequal,” and thus violate the constitutional rights of minority children to equal protection under the law.

In recent years, LULAC has focused on growing and exercising the political power of Latinos, through voter registration drives and other events that spur political consciousness and activity. LULAC has an education program, ¡Adelante! America, to help prepare Latino kids for higher education and support them once they’re there. The group has a health program, Latinos Living Healthy, to lower the health disparity between Latinos and Anglo America. Through the Hispanic Immigrant Integration Project, LULAC helps provide social and economic services to Latino immigrants. Plus LULAC offers a variety of financial and consumer services, and with its Empower Hispanic America with Technology initiative, LULAC “aims to empower the Latino community by increasing access to and utilization of key telecommunication technologies which have been historically been out of reach for many Hispanic Americans.”

LULAC indeed has a long and proud history of lifting Latino Americans out of poverty and powerlessness.

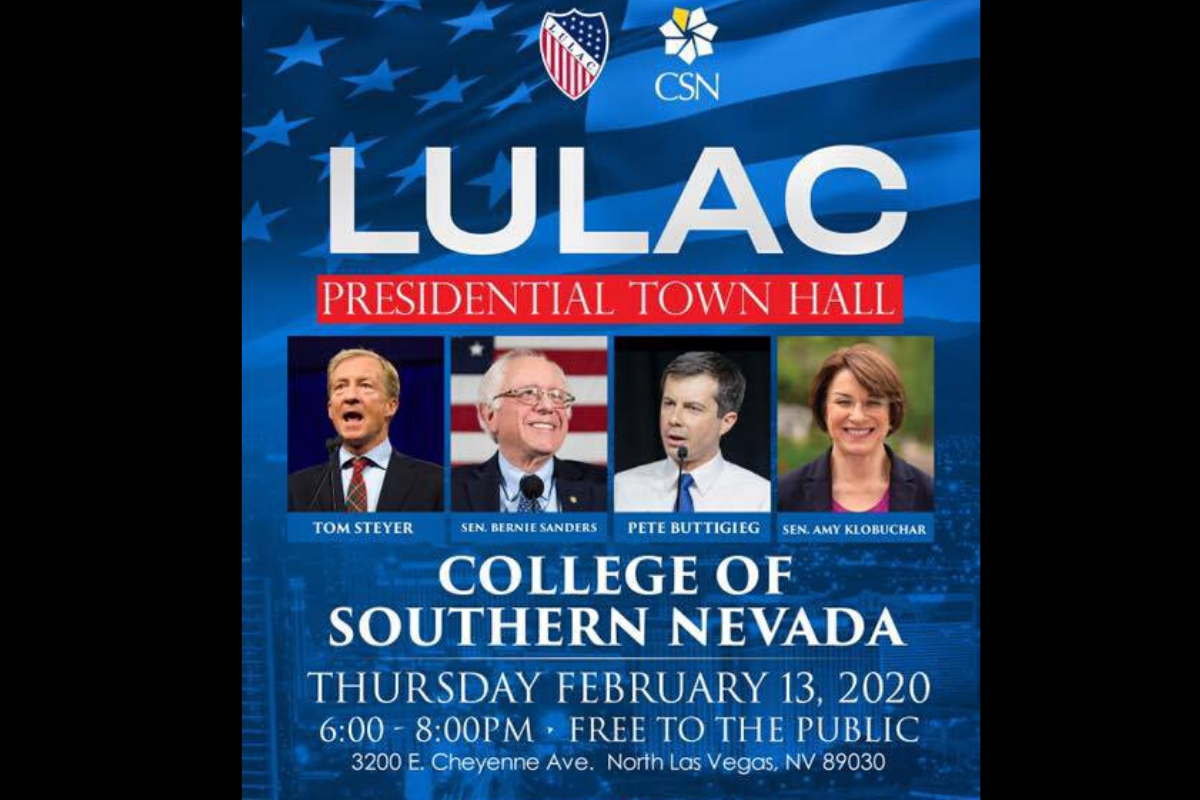

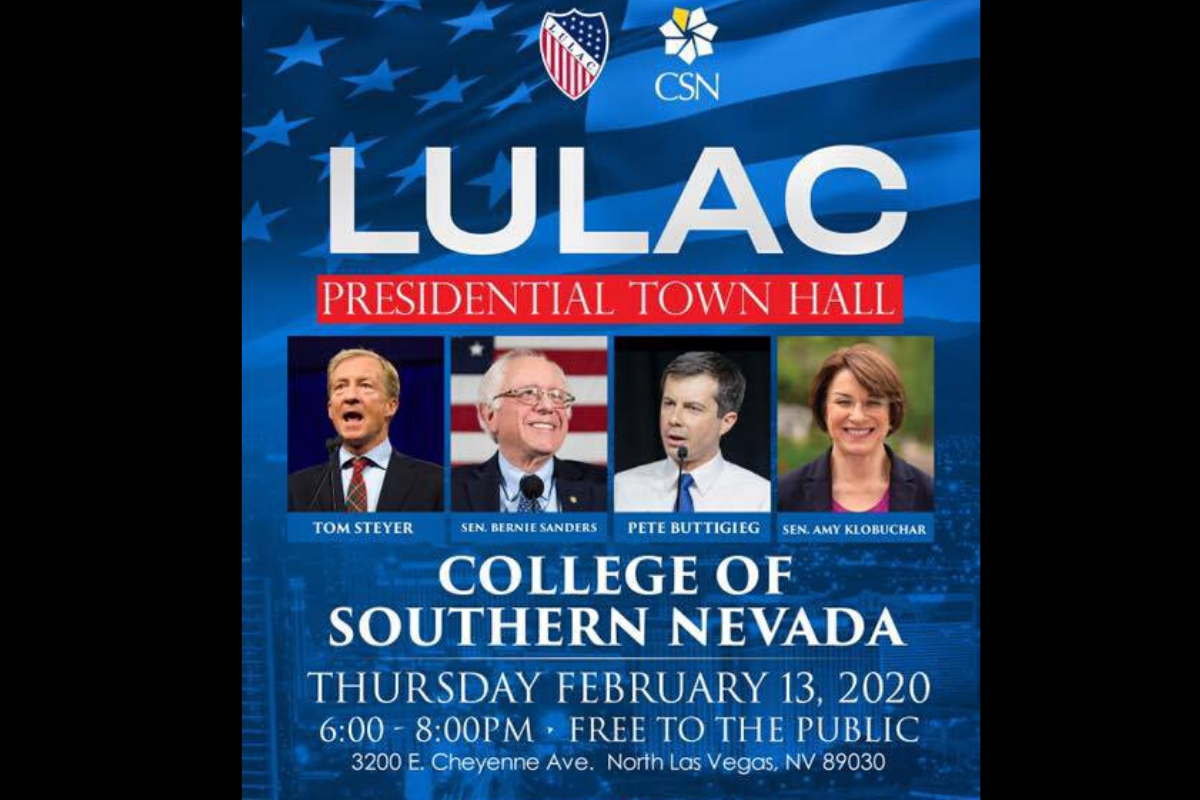

But when I tell a Latina —one Ms. Palma— that I’m going to a February 13 presidential town hall in North Las Vegas hosted by LULAC, she seems confused. “Lula’s?” she asks, wondering why a presidential town hall would be held at some restaurant. “No, LU-LAC,” I say, and explain how they’re the nation’s preeminent Latino civil rights organization, essentially what the NAACP is for…

I see her eyes yawn. She could hardly care less.

Ms. Palma is a 32-year-old Mexican-born American citizen, a junior partner at an original equipment manufacturer here in Las Vegas, member of a country club in the swanky MacDonald Highlands, on the verge of owning her own home, with a teenaged daughter who gets A’s and B’s and plays on the varsity tennis team—exactly the caliber of individual a group like LULAC seeks to attract. That Ms. Palma has never heard of the group, and doesn’t want to hear about it now, means LULAC has its work cut out.

It’s a few hours before the town hall at the College of Southern Nevada’s North Las Vegas campus, and I’m sitting with Sindy Marisol Benavides, the CEO of LULAC —the first woman to hold the title— and I ask her what she would tell a young Latina like Ms. Palma about her organization.

“LULAC is 91 years young,” she says with a proud but gentle smile.

“We’re 91 years strong. And that, really, LULAC is here to protect our community. And that, for 91 years, we have been protecting and defending our community,” Benavides says. “And for us, in 2020, it’s making sure our community has an increased consciousness about harnessing their leadership power, harnessing their ability to run for office and represent us at the highest level. Making sure that our community understands that their vote at the ballot box, when we add it up, one by one, can be transformational, in the way that Latinos are viewed in America. And that, when we are connecting with our youth members, who are high-schoolers and under, we are training them to be leaders. That when we are holding town halls, whether it’s in Milwaukee, or Des Moines, or here in Las Vegas. It’s to increase awareness about the issues that impact Latinos not only for ourselves, but to make sure that candidates are thinking thoughtfully about how they’re addressing issues that impact us.”

Benavides shares more.

“And I think, more than that, for us it’s also really making sure that we have the next generation of organizers. That we understand what advocacy is. That we understand why it’s important to raise our voices, and why it’s important that we show up and that people understand that a Sindy Benavides, or a Julio, or a John Medina, or whoever, that they understand that there is a name behind the numbers and that when you’re talking about specific policies, that impact our community, in higher proportion, that you know us by our name, and you see us by our face.”

Truth is, I fully expected to be skeptical of Benavides, and especially LULAC’s national president, Domingo García. From what I’d read about LULAC back in college, it seemed like one of those centrist minority groups that “advocate” for the members of their communities by telling them to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps, and pull their pants up too while they’re at it—and, as with nearly every civic organization, there are plenty of those respectability types among LULAC’s ranks, people who dress for a town hall like they’re going to see Hamilton on Broadway.

But I like Benavides. And García.

Benavides smiles easily and she speaks softly but with controlled passion, her voice getting firmer and firmer as she talks about her mission to push for and defend the economic and social rights of Latinos, until she’s clinching her jaw and pounding her right hand on the table—the same hand with a finger splint wrapped around her fore and middle fingers (she broke the middle one climbing some stairs). Plus it helps that she hails from Honduras, where my mother was born, and she reminds me of one of my aunts, only younger.

García, for his part, has a list of achievements that makes César Chávez look like a lazy hippie: “from shoeshine boy to the Statehouse of Texas”; born of Mexican immigrant farmers in Texas; degrees in politics, law, and international relations; a thriving law firm with over 500 employees; one of the youngest Latinos elected to the Democratic National Committee (1988); the youngest member of the Dallas City Council, on which he served from ’91 to ’95, and during which time he became the youngest person elected mayor pro tempore of Dallas; helped create the first Latino Cultural Center in the nation; voted to allow gays in the Dallas PD; a Texas state representative from ’96 to 2002, during which he helped pass the Texas DREAM Act, giving in-state tuition to undocumented students; helped organize the largest civil rights march in Texas history in 2006, when close to half a million people came out to support comprehensive immigration reform. The list goes on and on.

I ask García about the chances of seeing a Latino president anytime soon, considering the outbreak of anti-brown sentiment which has gripped half the nation like a plague.

“The fact of the matter is,” he says, “I think the first Latino or Latina president has already been born, and he or she is walking the streets of San Antonio or Las Vegas, or Los Angeles, and we gotta create that foundation, that legwork. Register people to vote, get them out to vote, get candidates to run for office, whether it’s school board or city council, get them elected to statewide office, develop a deep bench so that those candidates can run for the Senate and then eventually run for the White House.”

Domingo García (Photo via LULAC)

Sounds like a plan. So which issues or concerns does LULAC want voters to consider this election year?

“The way I’ll put it to you: Today, somewhere in America, José and María woke up, and they had to make a decision whether to pay the rent or get the insulin for their daughter who is sick, and that’s a tough choice. And more Latinos do not have health insurance, to cover an illness or disease, and are strapped and, you know, are just one paycheck away from bankruptcy. So health care. Who’ll provide health care for all? For every José and María and their families. Who can do that? That’s very important.”

García continues.

“María’ll wake up, and so will Sofía, and they’ll clean hotel rooms here, in Vegas, and they’ll be making close to minimum wage, with little to no benefits, even those who are members of unions. So the question is: Why aren’t they being paid for equal work? Sofía and María should make the same amount that an Anglo man makes for the same kind of work, but they make 53 cents on the dollar. And that needs to change.”

He is in full political pitch mode now.

“Third, immigration reform. Can you believe that here we are in 2020, and there are children’s prisons, there are concentration camps, full of refugees just seeking a better life? We need to reform our immigration system. Which presidential candidate will tell José and María, ‘We’re gonna take care of your abuelita, your tío, and we’re gonna figure a way to get them reunited and these families reunited, without the fear of ICE raids and the separation of families and children being put into concentration camps’?”

This is all well and good, but it’s a nonstarter with Latino voter turnout as shamefully low as it has been since forever —though Latino turnout shot up to 40 percent in 2018, with a record 11.7 million Latinos voting in the midterm elections— still, that’s nowhere near the 51.4 percent and 57.5 percent turnout rates among black and white voters, respectively. With the lack of economic and political power Latinos have in this country—Latinos seem to be doing a little better than blacks economically, but lag far behind whites and Asians; and there are 13 more black members of Congress than there are Latino members, but who’s counting? And with the demographic changes in Latinos’ favor, you’d think Latino voters would head to the polls on Election Day in swarms to secure their piece of the American pie. And yet…

What’s up with that, Mr. García?

“You gotta have a candidate that invests in the community to get the vote out. And Harry Reid just spent five million dollars, in Las Vegas, just to get the Latino vote out here to win a statewide Nevada race.” He’s referring to Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, who in 2018 became the first Latina elected to the Senate. “If people started investing, you will see that people will go out and vote, and we’ve seen it in Iowa where we did have a record turnout of Latinos for the first time. We had bilingual caucuses, satellite caucuses, that turned out. But, you gotta ask them, you gotta talk to them, you gotta talk about kitchen-table issues that we talk about, education and health care, immigration reform, and. income inequality, and those are issues that are important, and if somebody addresses those and gets them out to vote, they can make a difference.”

“The revolving problem,” says Benavides, “is that nonprofits can’t do it by themselves, and it will take candidates, it will take campaigns, it will take the RNC, it will take the DNC. It will take all the political structures investing, and making sure we have Latino staffers. Latinos making decisions within the campaigns. That there is money being put to political ads, both in English and Spanish, and online. That we are actually investing and expanding the universe, because we have many Latinos who are eligible to register to vote who yet have not registered to vote. And just a big reminder to Democrats, that that was a strategic tactic that was used by the Obama campaign, to expand the universe of voters, and be able to provide that win margin.”

“I will tell you that we are awake,” Benavides adds. “But it will take more than just words. It will take more than just one organization mobilizing. It will take everyone’s effort, including political campaigns, to truly invest to make sure that we turn out to vote. Because we will not just take it by your word. We wanto to see actions.”

“You’re firing me up over here,” I tell her.

She laughs. “Can you hear the passion?”

It may surprise you to learn —though maybe not, but it surprised the hell out of me— that LULAC supports Medicare for All, and making public colleges and universities tuition-free; and that, all its prestige and respectability aside, LULAC is essentially a grassroots organization geared toward the working class—that is, lifting working-class Latinos up into the middle and corporate classes. For better or worse, they’re really trying to help Latinos, in both the Booker T. and the Du Bois molds: training the majority of Latinos to be of service to American society, while nurturing a Talented Tenth to share command of it.

Soon, in the theater’s foyer, the college’s co-ed mariachi band, Mariachi Plata, is in full swing, as a long line of attendees snakes its way into the auditorium. Four collapsible tables are set up along one wall, one for each participant in the town hall: the mayor of South Bend, Pete Buttigieg; the billionaire hedge fund manager, Tom Steyer; the senior senator from Minnesota, Amy Klobuchar; and the junior senator from Vermont, Bernie Sanders.

The Steyer table is mostly yellow, displaying buttons and shirts reading TODOS CON TOM with different shades of cartoon fists in the air. Because I liked what Steyer was saying in the last debate, in New Hampshire, or maybe because the young Latina sitting behind the table shot me a curious eye, I approach that table first to get a closer look.

After I tell her and the older white lady seated next to her who I am and who I’m with, her eyes light up as she extends me a hand, telling me, in Spanish, that she met Julio (Latino Rebels founder) in Texas during some campaign for a Spanish name I haven’t heard of—at least, I don’t think I have. “Do you have a card or something you can give me?” she asks.

“Naw,” I grin, lifting up a foot to show her my shoes. “I’m wearing sneaks with skinny jeans: I look like a guy who hands out his card to people?”

“Yeah, that’s old school, I guess.”

I tell the two ladies I like what Tom’s been saying, and how I wonder why he isn’t more popular. But they’ve been hearing good things from voters, they say, so they’re optimistic. When I tell them I’m caucusing this year —I’m from Illinois, so I’ve never caucused before— this time the older lady’s eyes light up, and the Latina hands me a bumper sticker.

I move over to the Klobuchar table, mostly green, manned by two millennials, a girl and a guy. I ingratiate myself by telling them that my wife is impressed with Amy, always nodding or giving some approving remark whenever she hears what Amy has to say. I ask them what they’ve been hearing from voters, and how they think Klobuchar can win voters over from the Buttigieg camp, her main rival within the neoliberal wing of the party.

“Well,” the guy begins, but then he catches himself. “You’re not gonna write this, right?” I reassure him with a swipe of my hand. Then he tells me something about how he’s confident Klobuchar can win voters with her “proven record” and “experience” of “pragmatic.”

“But wasn’t that Hillary’s pitch in 2016?” I interject. “And look what happened there.”

This clearly bugs the shit out of him. He huffs, assuring me that Klobuchar has a clear path to victory not only in July, but November, too. I wish them luck, take a green Amy button for my wife, and head over to the Bernie table.

There’s a brown guy standing behind it but he speaks with a drawl. Turns out he’s Canadian, and we get to talking about how Bernie’s platform isn’t much different than what they already got up there in Canada and over in Europe, and how, despite what the mainstream media’s been saying, Bernie appears to have the broadest coalition of supporters among any of the other candidates —blacks, Latinos, Asians, Native Americans, gays, Christians, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, atheists, cooks, teachers, activists, artists, lawyers, you name it— all in huge numbers. Bernie voters are everywhere. You just have to go around asking different people to know that’s the truth.

I head over to the table on the opposite end from Bernie’s, the Buttigieg table, mostly blue and gold. There’s a sharply dressed young Latino manning the table. When I ask him what he’s been hearing from voters, he goes, “We’ve been hearing a lot of good things, but”—he points at my media badge—”I can’t talk to you.”

“Very professional, Pete,” I say, nodding slowly. “Very professional. Well, good luck anyway.”

Signs posted here and there direct me back to the MEDIA SPIN ROOM, a tiny black box theater where the town hall in the much larger auditorium will be projected up on a hanging screen. On the little stage, below and a bit behind the screen, a row of news cameras are set up on tripods, facing a podium with microphones and a LULAC backdrop behind it, for the candidates to answer questions after each has survived his or her portion of the town hall and has left the auditorium.

It only takes me a minute or two to realize I’m the only brown journalist in the room, which is a tad strange considering the event is hosted by LULAC, alongside Leticia Castro from Telemundo Las Vegas, but oh well. The people in that media room were something else, too, a mash-up of geeks and yuppies but I’m already a few thousand words into this thing, so I’ll leave that story for another day.

Before the thing kicks off, a man who looks like a built, bronze, walking version of Professor X comes out and reminds the audience there are to be “no signs, no badges. LULAC is a nonpartisan organization.” The man is David Cruz, LULAC’s communications director, which I might’ve guessed from his news-anchor dialect. “No outbursts from the audience,” he says, and quotes Benito Juárez: “Respect for the rights of others is peace.” Then he introduces “the future face of LULAC,” a dapper white Latino who looks a bit like Gael García Bernal, with slick hair and a bow tie. He comes out speaking Nahuatl, and then makes a point of acknowledging that Las Vegas sits on land stolen from the Southern Paiute Indians. His name’s Joél-Léhi Organista, and he’s the LULAC national vice president of youth.

The event starts.

Leticia Castro from Telemundo Las Vegas —and Nuestra Belleza Latina fame— is on stage introducing García, who comes out and starts with “the story of José and María.” Then he introduces Dr. Federico Zaragoza, the first Latino president of the College of Southern Nevada, who introduces Ms. Benavides, who introduces the first candidate, Tom Steyer—but not before she says, “Our very identity makes us targets. We too are Americans! ¡Somos americanos!”

Steyer bounds across the stage with a “¡Buenos noches!” and launches into how he’s running for president “to break the corporations’ stranglehold on government.”

Thankfully I see Latino Rebels has already posted the full video of the town hall, so I don’t have to go into details of what was said.

That leaves me enough space to give my impression of each candidate:

Steyer

Democratic presidential candidate Tom Steyer participates in a LULAC Presidential Town Hall at The College of Southern Nevada February 13, 2020 in North Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

The more I hear this guy talk, the more I wonder why he isn’t more popular. He’s a billionaire businessman who talks like Bernie Sanders, and even stresses the demand for social, economic and environmental justice for women and people of color more than Bernie does—though, of course, Steyer is about as socialist as Lizzie Warren. He talks about the “corpocracy,” about how “what’s going on in immigration courts is racist,” how he wants to “decriminalize the border,” about “the crimes against humanity at the border,” about “environmental racism”—”I don’t like the word pollution; these companies are poisoning people.”

Why hasn’t the public heard more about this guy?

Did you know Steyer was co-chair of the Latino Victory Fund in 2016? Did you know he and his wife founded a nonprofit community bank in the Bay Area for underserved communities, small businesses and other nonprofits? Did you know he’s the man behind NextGen America, the progressive political action committee which, among other things, registered over 250,000 millennial voters in 2018? Did you know he’s for DACA and DAPA, and that, when it comes to ICE, he talks about the need to “prosecute people who terrorize people”?

Steyer is skeptical about Medicare for All, though: he doesn’t think we need to scrap the current system full stop. So, on the face of it, he seems to be somewhere between Bernie and Lizzie—which only begs the question: Why isn’t this dude more popular? Because he looks like a typical old white guy? Has the nation become that color-blinded? Or is it the money? Are the rich automatically suspect? (Is that a stupid question?)

Back in the Spin Room, a young journalist asks Steyer, “Is the Democratic Party too liberal?” She’s standing right next to me, and I laugh to myself and shake my head.

Sanders

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders, via video conference, participates in a LULAC Presidential Town Hall at The College of Southern Nevada February 13, 2020 in North Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Bernie’s up after Steyer, and though he’s a full 15 years older than Tom, he looks and acts younger, more vibrant, a pro with the public. He is not on stage, but speaking through video conference. Besides Bloomberg —who couldn’t be bothered appearing at the LULAC town hall, just as he can’t be bothered with much of the nomination process— Bernie’s the most presidential, someone who looks ready for the job on Day One.

What else is there to say about Bernie? He’s the most progressive candidate on offer in the Democratic Party. He’s pushing for Canadian-style democratic socialism, and he’s been fighting for the same causes for as long as anyone can remember.

I found it curious that he was the only candidate at the town hall asked about Puerto Rico —two questions, in fact— and> he was asked about sex workers’ rights by the student government vice president. No one asked Pete or Klobuchar those questions.

There was also that question from a middle-aged Latina about stopping the “generational abuse” of welfare programs. I’m pretty sure I know what that was about, too.

Buttigieg

Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg participates in a LULAC Presidential Town Hall with Telemundo news anchor Leticia Castro and LULAC National President Domingo García at The College of Southern Nevada February 13, 2020 in North Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Mayor Pete came out stiff as a board. This guy’s like an old man in a boy’s body. He’s too eager to be president. You can’t trust someone that young who wants that much power—take it from me. But his Spanish isn’t bad, I’ll give him that. Shit, his Spanish might be better than mine, especially considering he has to answer questions about foreign and domestic policy in front of all those people, under all those hot lights, with all those cameras watching. I’d probably choke on my tongue, or say “pinche” too much.

But he’s too practiced. I know guys like this, we all do, and no one likes them, so why would we ever make one our president? Are the voters that masochistic?

Pete and the Wall Street bankers who support are trying to screw over the American people, and anyone even remotely paying attention can see it from a mile away. Those not-so-secret dinners with rich donors—he doesn’t care if you catch him cozying up to Big Money. The way he says “Latino”—if you’re Latino, you know what I mean: Pete says “Latino” the way Obama said “Taliban,” as if it were so utterly foreign to him. It feels to me that all his words drip with condescension bordering on contempt, as if he’s gracing you with his mere gaze and the sound of his voice. Watch the video from the town hall: I felt as if he even didn’t want to take questions from the commonfolk, much less explain himself to them.

And watch when he gets a question how he’ll close the concentration camps on our border when he doesn’t even condemn the Uighur camps in China. How dare did a brown kid ask a question like that?

Poor Pete. If only there were a way for Pete to become president of the United States without him having to actually deal with the people of the United States—like Bloomberg.

Maybe Pete just reminds me too much of Mayor Rahm in Chicago. The way he speaks. His mannerisms. Maybe he’s just too much like Hillary for me

No wonder he decided to skip the Spin Room afterward.

“And face the wrath of the national press?” says this affable Asian guy, who seems to be the prince of the Spin Room.

“He’s only running for president,” I add.

Klobuchar

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Amy Klobuchar participates in a LULAC Presidential Town Hall at The College of Southern Nevada February 13, 2020 in North Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Oh, Amy…

I don’t understand how anyone thinks Amy Klobuchar can and will be president of the United States. I don’t believe she believes she can win the nomination, much less the election, so why is she even running? For her measly 15 minutes of fame? Our celebrity culture invades and rots everything from the inside out. Now it’s all about being seen and heard for as long as possible to raise your cachet—the kids call it “clout.”

Do me a favor: Close your eyes and imagine Amy Klobuchar flying around the world on Air Force One and meeting with foreign dignitaries as president of these United States. You can’t do it, can you? No one can. Can you see her with Putin? Or Xi Jinping? Or even Kim Jong-un? Or Boris Johnson?

Amy would be the first woman president, of course, but even then it would still be a downer. Like a box of chocolate milk—it’s alright, but…

She touts the fact she’s won elections going all the way “back to the fourth grade,” but that’s probably because she’s so bland and boring that people figure she can’t do much damage either way. She drones forever during her answer about criminal justice reform, to the point that Mr. Cruz cuts her off. (“I’m so passionate about it,” she says, “I can go on and on.” I have absolutely no doubt about that.)

I think I’m going to start playing audio of Klobuchar explaining her policies every night, just to help me fall asleep.

That said, I’m sure she’s very popular with the goody people of Minnesota, and if so, they can keep her.

Just another night in Vegas.

***

Hector Luis Alamo is the Editor and Publisher of ENCLAVE and host of the Remember the Show! podcast. He tweets from @HectorLuisAlamo.

[…] also wanted to mention how well Klobuchar did, since I was pretty harsh last time. She was so personable and straightforward, even funny here and there, though mostly bland and low […]